David.

I’ve not felt like writing this year at all, but I know from previous experience that when that feeling is ready to pass I will just get this… compulsion to put fingers to keys as there’s something I need to get out. I’m still processing the last six months, which have contained the most significant personal events since my mother’s passing nearly four years ago. I know what loss feels like. In the last few weeks I’ve talked to several friends who’ve asked for my version of events so, perhaps in some desire to not forget anything, I’m going to try and write down what’s happened.

As it’ll be long I’m making a decision to do something I’ve never done before, not a diary exactly, but to split the events into different months. A friend told me that the lead-up (the play, the album, the holiday) to Bowie’s passing is the most remarkable part of my version of the story, and I know what she means. She asked me if there was a word to describe how that feels – to be on the top of the world, with no idea something awful is coming – and I don’t think there is, but it’s certainly… cruel. Perhaps all this would have been easier if he’d shuffled off this mortal coil in 2007 or 2009 or 2011, when he was just doing his thing, at home, with seemingly no interest in making music at all. I now realise how lucky we were not to lose him in 2004. Gail Ann Dorsey relating what happened when he had the heart attack, which nobody present had spoken about before, chilled me to the bone. But he didn’t die in 2004, or during 2012, when he was making his return record, The Next Day. He came back and gave us three more years of music, which only seems to have made coping with losing him worse.

One day perhaps a book will be written about the making of Blackstar. But, briefly, what we know so far is that during his cancer treatment he went into the now-closed Magic Shop studio two blocks downtown from his Manhattan apartment and recorded in the first week of each month of January, February and March 2015, as much as chemo would allow (I know all about the effects of chemo, sadly, and one week’s work in a month sounds about right). His initial idea was to continue the collaboration he started with Maria Schneider the year before on Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime) (single edit), but by then she had committed to her brilliant Grammy-winning record The Thompson Fields. As she couldn’t help out, and he didn’t have time to waste, she recommended one of her principal musicians, saxophonist Donny McCaslin. She pressed a CD of his excellent album Casting For Gravity into Bowie’s hand and advised him to visit the jazz club Bar 55, which he did without fanfare, to see Donny’s quartet play. He invited the band (on drums the remarkable Mark Guiliana, Ben Monder on guitar – they both appeared on Sue – Jason Lindner on keyboards and Tim Lefebvre – whose day job is with the Tedeschi Trucks Band – on bass) to play on Blackstar, sent them highly evolved demos and they made the album. That’s the short version of what happened. Tim Lefebvre has done some excellent interviews about the process, like this one, which are well worth seeking out. Bowie and Visconti produced the record and it was completed over the next few months. At the same time, incredibly, Bowie was also working, with playwright Enda Walsh and director Ivo Van Hove, on a sequel of sorts to his first starring role, The Man Who Fell To Earth. He would record/produce Blackstar during the day then head to Enda’s flat to co-write this new play, Lazarus, at night. It was a race against time in every sense. That’s the background. Here’s where I come in.

August

Lazarus was due to premiere in New York in December. I can’t remember whose idea it was to go, but it was based on getting tickets to the opening night, which our wonderful community of Bowie freaks had decided on as the night we all should go. When they went on sale Leah and I were at the mercy of friends who’d joined the New York Theatre Workshop and we crossed our fingers for a pair. Charlie Brookes was our saviour and tickets were procured (on the night, BowieNetters dominated the theatre, with probably 60+ of the 198 seats taken up by friends), at which point the search began for accommodation and flights. Division of labour is the best way to plan a holiday, so Leah did the flights while I trawled Airbnb for suitable apartments. The first couple of days were fun, looking into people’s houses and lives, but the novelty wore off quickly. After a long week of searching I found a pretty perfect, sparse, one might say minimalist, 3rd floor walk-up apartment on East 14th Street and Avenue B. It was near NYU, where Leah would work during the day (it’s how she got a week off work mid-term, by being a visiting scholar). Everything was booked.

September

Nothing momentous, comparatively, happened this month. I worked on an inflight magazine. I went to see the Rocky Horror Show a few times. We went to see Morrissey, which was, as ever, fantastic. My 16th time seeing him – that’s one more than Bowie. Though if we’re going to be technical and nerdy about it, which I always am, I’ve seen Moz 17 times because there was that gig at the Roundhouse where he sang three songs and walked off (lost voice), but I also saw Bowie in person twice more for TV shows, so really that’s 17 as well. I digress.

October

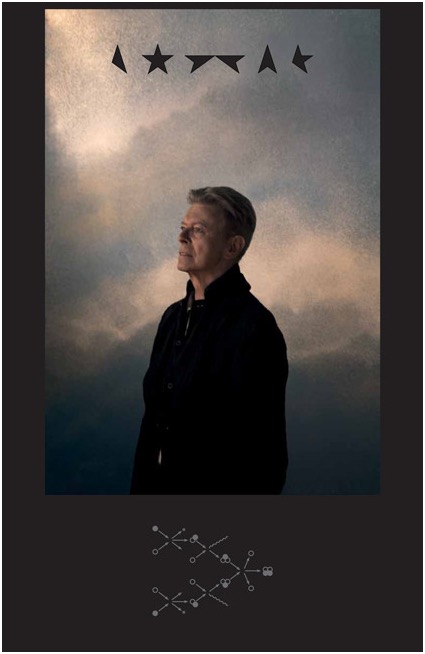

Bowie announces to my excitement that his new album Blackstar will be released on his 69th birthday on January 8th 2016. The Blackstar single and video were to be released on November 19th and it felt like all was good with the world. A New York trip to look forward to and a new album were more than I could ever have hoped for. I think now of how we all waited nearly a decade between Reality and The Next Day and it seems like another lifetime.

The week before the song premiered, my friend Mark and I drove to Cambridge University on the 11th to see Leah do a talk about Bowie and what was coming. At that time we had only a 30-second clip of Blackstar from the opening titles of the Sky series The Last Panthers (directed by Johan Renck, who also did both Blackstar videos). It was a fun evening, filled with excitement about the new record and a seriously brilliant presentation on his music (yeah, not on his hair or his clothes; on his creative practice and life as a composer, plus awesome data analysis).

On the 17th dad, Leah, her partner Ben and I went to see the Maria Schneider Jazz Orchestra at Cadogan Hall, near Sloane Square. We sat front row and it was just fantastic, what a great night. McCaslin, who dad says reminds him of the late, great Michael Brecker, was the lead soloist, blasting away five feet in front of me, and I had not a clue in the world he was on Blackstar. I heard the song for the first time two days later.

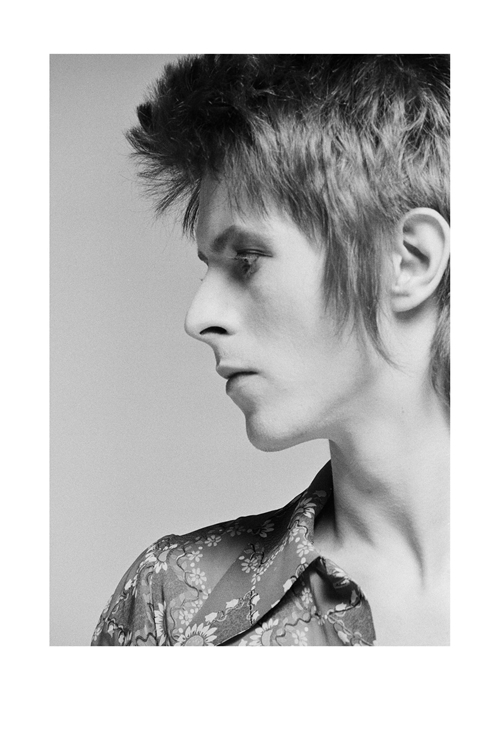

I feel so grateful now that I have a relationship with Blackstar, the song, which predates the events of January. The video (shot in September) is a masterpiece and I obsessed over it for days, then weeks. The song I think is absolutely one of the best he has ever done, and it’s starting to rival Teenage Wildlife for my Bowie Desert Island Disc. I did think he looked old in the video but then, he was pushing 70 and the flattering camera filters and copious make-up used for the videos from The Next Day were clearly no longer being employed. It was clear to me that he had finally released all vanity and was just being seen; he looked so engaged, enthused and vibrant in the video, and it gave us all so much pleasure. Some fans had said they hated jazz then had no choice but to grudgingly accept it when Sue came out because it was such a brilliant record. The same people were now faced with yet more non-pop music that challenged them, which as a jazz nerd I took a perverse pleasure in. Bowie does jazz? Then hires five jazz musicians to play on his last record? It’s like all my Chanukahs came at once.

December

For the first time since Bowie last toured, a big contingent of British (and some European) BowieNetters made their way to New York, to be united with our American BowieNet family. Leah and I arrived on Saturday the 5th, in the evening, and decided to do a bit of grocery shopping and spend our first night in the apartment. My recollection is that we watched The Wiz Live! on TV and fell about laughing at how terrible it was. We met up with the legendary Dick Mac on Sunday and went to the famed White Horse Tavern, once the haunt of Dylan Thomas, Kerouac and other luminaries, and then for dinner. It was at that point that I met Paul, Leah’s friend from Brisbane who’d come over for the show. What a fantastic guy, I adored him from the first minute. We headed over to Otto’s Shrunken Head, a dive bar three doors away from the apartment (we’re no fools!), to meet up with Bowie friends. My remembrance of the evening is somewhat coloured by pints of cocktails followed by a 4am stagger into bed.

The Monday contained perhaps the worst hangover I have ever had. Mountains of sushi did nothing to calm it, so as Leah went to work I hooked up with my wonderful friend Jake, my daytime companion, and off we went on a pilgrimage I’d always wanted to make, one that my mum talked about often, which was to see the grave of Miles Davis, up at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. I felt so ill, I can’t even tell you. But we made it, with Jake’s excellent navigation, and I paid my respects, which mum would have been proud of, before we headed to Harlem to visit Langston Hughes’s house then eat at Sylvia’s, the legendary soul food place. I put my head on the table and struggled through a bit of food (mac and cheese, and little else; not much available for the vegetarian). We went to the legendary Apollo, where I bought dad some gifts (and impressed the guy behind the counter by identifying Miles in a photo collage in two seconds) and then walked down to Central Park, laughing hysterically all the way. We were a bit worried about Lazarus not being any good and had a few parodies ready at its expense (mein herr!). Jake was flagging and bailed out of evening activities, which were dinner at Sigiri, a Sri Lankan restaurant (too spicy, I was still ill), followed by some live band karaoke at Arlene’s Grocery.

This was the day of the play’s press night – Monday the 7th – and many of our friends had gone to the theatre to wait outside to see if Bowie would turn up. It never occurred to me to do the same, it’s not my kind of thing. I saw him live plenty of times, I didn’t need to watch him walk into a theatre for five seconds, but I’d be lying now if I said I wasn’t at least slightly regretful that I didn’t get to see him in person one last time. At dinner, Leah showed me the pictures that had been posted on our Facebook group; indeed, he had turned up of course, looking happy and handsome, taking his bow on stage at the end with Ivo and the cast. Friends came to join us at dinner, straight from the theatre, looking high and glazed, having laid eyes on him for the first time since 2004 (a few others had seen his final live appearance in 2006).

That night at Arlene’s Grocery (Leah performed Superfreak and I don’t think I’ve ever laughed so hard in my life) was one of the most fun nights I can remember. Everyone was so incredibly happy. To be in New York, ready to see his play, most having seen him in the flesh earlier in the evening, it was a beautiful, special night. People got up and sang and the organisers were amazed that so many of us in the bar had flown over just for the play. I think we watched Tootsie when we got home (might have been the night after).

The next day, Tuesday, after a bit of gift buying, Jake and I spent the afternoon in the Mad Hatter, a Man City pub, believe it or not, watching City play. We won in the last few minutes, which felt fitting for such a trip. Then we all went to a friend’s party at her apartment, which was so much fun, one of those proper New York evenings where you feel like you’re in a movie. I wasn’t sleeping well of course, in a strange bed, using earplugs to block out the famed NYC hum, but I didn’t care. Subsisting on four hours a night on holiday is par for the course, even if it does later in the week lead to sleep-deprived, jetlag-induced hysteria. I don’t think have ever laughed as much as I did on this holiday.

Wednesday was Lazarus day and my friend Kate was flying in just for the show. I had not seen her in several years and we’d arranged to spend the day together. After another play of Blackstar on You Tube, Leah went to work and I went to Katz’s Deli on East Houston for breakfast as I waited for Kate’s plane to land from Ohio. She’s a hairdresser and we had organised to meet at the Aveda salon on Prince Street. In between Katz’s (a 10-minute walk downtown from our apartment) and Aveda is a building on Lafayette Street we now no longer need to pretend we don’t know about. There is a collection of penthouses and Bowie’s family live in two of them. I’ve walked past it and looked up many times over the years, even though I didn’t know which penthouse was his and nor did I care. It was kind of lovely to just know he was up there, tootling around in his man cave, making demos in his studio, reading and emailing incessantly, doing school stuff with his daughter, just doing New York things. A friend of mine, Lori, who works downtown, said that she would always wave up to him if she happened to walk past the building because she knew “he was up early too”. She didn’t wave because he could see her, nor did she walk past because she ever wanted to bump into him on the street (can you imagine! I’d have run a mile if I’d ever seen him slinking around, with his flat cap on). She did it just because he was there, and it was good to know he was just living life in his city, like we all live our lives in our cities and towns. I walked right across the front of the building to get to the salon and I looked up and smiled, wondering if he was happy with Lazarus and how the press had received it. Kate’s plane was delayed so I took a walk around the neighbourhood and popped into the Taschen store on Greene Street, which happened to have Mick Rock’s huge Bowie book on display. When Kate arrived we leapt into each other’s arms like we’d been apart a hundred years. After a quick drool over the Bowie book back at Taschen we got a ludicrously slow taxi uptown to meet a friend of hers for lunch, then came back down to meet up for a long coffee date with a big cheese at Aveda. He was English and seriously good company, the kind of guy who remembers very little of the 90s in London. It was time for Lazarus.

Early the next morning we decided we had to see it again on our last night in the city, so I resolved to go down to the theatre while Leah was at work and get more tickets, which I did. It made a more complete picture, as much as it could, the second time. Our last night in New York was spent in the apartment with a couple of beers just watching TV, out of sheer exhaustion. On the final day we went, with Paul, to Katz’s for brunch, then did a lovely walk around the Highline, before heading off to the airport, where we had a few glasses of celebratory Prosecco at Sammy Hagar’s Beach Bar and Grill (really) before a night flight home, landing on the morning of the 12th. It was a landmark trip.

We got back to real life and work, and the Lazarus single was released on the 17th (with the video to come 3 weeks later). Hearing Bowie sing it was kind of strange, given that we’d seen Michael C. Hall do it live on stage (and on Colbert’s Late Show on the 18th). It felt like Bowie’s ‘version’ of the song from the play almost! New year came and went. At some point I’d committed to going to a playback of Blackstar at the Dolby offices in Soho, with a group of BowieNetters of course, so I had a ton of stuff to look forward to in the first week of…

January

On Thursday the 7th the Lazarus video (shot in December) premiered. I thought the hospital bed stuff was kind of dark and a bit physically unflattering but that the sections with the stripy outfit (the master of the call-back strikes again, for the last time) were amazing and he looked fantastic. Leah and I talked about how great he looked, those cheekbones! I can’t stress enough how nobody thought he was unwell. All press coverage of his appearance at the Lazarus premiere focused on how great he looked. Yes, he looked thin, but he often did; no alarm bell was raised.

The playback that night was fun, if a little too loud, and I saw some of the same people I’d been with in New York. On Friday, his birthday, I listened to Blackstar on repeat all day. It was a lot to take in, but Dollar Days was already even then able to make me weep. I listened to it several times over the weekend. Some of the tracks I already knew – the title track was already well embedded with seven weeks of plays under its belt; Lazarus had been making me crazy in a good way for three weeks (that sax solo breakdown, my god!); the new heavy version of Sue I loved as much as the majestic jazz version from 2014; Tis A Pity She Was A Whore I knew the demo of, as Sue’s B-side; the other three songs were new to me and I devoured every note. What a weekend that was. A new Bowie album to obsess over! I was so happy. A happy idiot, like Wile E. Coyote standing at the bottom of the ravine, with not a care in the world, and not a clue that there was a huge boulder plummeting toward my head.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The beginning of Monday morning – January 11th – was a bit of a blur. I thought I heard my phone make the noise of a text alert and I roused myself from my pillow. I picked it up and saw that it was around 7.40am, and I had not one, but three, texts. I unlocked the phone and saw that I had three messages from three people who know me but not each other. I stared at the unopened messages and saw that all three had the word ‘sorry’ in the first few words. My brain works fast in the morning and, this is where you think I might be pretending that this is true, or even lying about it, but I am not: I knew he was gone. I knew in a split second that I was receiving these messages because my icon was gone. When they found out their first thought was of me. And in their shock and upset they were compelled to reach out to say something. There is no person other than David Bowie that would produce such an effect in every person I know. I didn’t even open their texts until later in the day. My head started to spin and I could feel my face going red, with panic setting in. I bounced out of bed and, shaking, opened the lid of my computer and went straight to BBC News, as that’s where you go when you want to know if something is true. His face filled the front page; I think the photo they used at first was from the Brits, 1996. I can’t really describe how I felt; I don’t think the words exist. I ran downstairs to my flatmate, in the kitchen, and burst into tears. He didn’t know how to react. I ran back upstairs and just sort of paced around for a minute, with no idea what to do. I feel sick and dizzy and flushed just thinking about it.

My phone started buzzing with more texts, emails started coming in, Facebook messages. I knew I had to call dad even though it was early, around 8.20am by now. I was in a terrible state. He later told me that when I called and said, through sobs, ‘he’s gone, he’s gone’ he thought I meant Dylan at first. He tried to handle me but it was impossible; he was pretty distraught himself and I had a flashed thought that I was glad my mum and my friend Rex were not here to see this. I called Leah and she just seemed to be in shock – Ben woke her only a few minutes before I called and told her and she said, ‘don’t be daft, he can’t be’ – and we had the phone call I’d been dreading for as long as I can remember.

Even then, at such an early stage, we marvelled at how he had pulled off the perfect rock and roll exit, a more flawless piece of death art you would never see. The man had class, right to the end. He had set it all up – from the play to the album – and executed his plan to perfection. We even laughed, and it felt good to laugh, to do that rare thing where you cry and laugh at the same time. I had been invited onto the BBC’s One Show that evening to represent my team in the FA Cup draw and I said, ‘how can I go? How can I be normal and smile on TV and pretend I’m ok?’ She said I should go. I took a pause, and said, ‘I have to do it don’t I? The show must go on!’ And we both laughed again. She had to go to work but we’d talk later, throughout the day. I remember when Lou Reed died (on my birthday), a couple of years before, we had this ashen-faced conversation on the Tube about what we’d do when Bowie goes. It gave me a shudder, like someone walking across a grave, just talking about it. Whichever one of us hears first, about Bowie, should call the other one, was the agreement. I sat on the floor and felt hot tears rolling down my face, unable to catch my breath, rasping and coughing, reaching for tissues.

I decided that I was going to go to the BBC that night. I had to do something instead of just sitting in my room. My eyes were hurting. I felt like I was losing it, in a dream state of some kind, so I had to try and do something normal. The BBC News channel had been running the same package for about three hours, while they put together a real tribute. They changed it at about 11am. By then the talking heads were on, and none of them were doing justice to what I felt. I wasn’t interested in listening to pundits who met him a couple of times. The next thing I remember was deciding that I could no longer sit in silence and that I had to face listening to his voice at some point, so at about 3pm I put the sound on; I howled, it was like pulling off a bandage, getting a jolt of searing, shocking pain. I Skyped Dick Mac in New York and we cried together. I talked to Kate in Ohio and did the same. I wrote something on Facebook because I had to get down how I felt, much like this. Then I pulled myself together and went into town – I walked to Heddon Street and talked to some strangers, then looked at the flowers, got down on one knee and wept. Some guy with a camera interviewed me but I don’t remember what I said. I got the bus to the BBC building near Oxford Circus, meeting my friend Andrew, who works there, to hand over a Blackstar badge I’d promised him and we just tried to talk to each other like we weren’t living through a nightmare, making each other laugh with weak jokes while he gave me a little tour. Being at the building was pretty surreal, with its huge screens everywhere, all playing a loop of their tributes. His face covered every wall. I pretended to be a human person and did the One Show, wearing a Bowie shirt under my football one. I tried to talk a little to my fellow football fans and they did the ‘yes, ooh, it’s terrible, I can’t believe it, wasn’t Heroes a great song’ sort of blurb and I nodded and thought, ‘you have no idea how I feel today but that’s ok. I envy you.’ When the filming started I positioned myself where I knew the camera would have me on TV the entire way through the broadcast and cup draw. When the green light went on and the hosts started their monologues I put my hand on my heart and thumbed the Blackstar badge on my jacket lapel for the camera. I didn’t know if anyone could see me and I didn’t care. But I knew what I was doing. When I got home there was a message waiting about Leah, Jake and I meeting in Brixton to go to the mural and lay some flowers the day after and I said I’d be there. I passed out from sheer exhaustion at about midnight. One day had felt like a month.

I took short breaks from crying on the Tuesday and got back to work. I’d done some pieces of work on Monday and continued to do so; the distraction was valuable. People kept asking me if I was ok and I kept replying ‘it feels exactly like I thought it would’. So many said that they were shocked at the outpouring of grief. I wasn’t. It all played out exactly how I knew it would – nothing surprised me about how people were reacting. I knew when he went it would be a big fucking deal, and it was. I’d feared the day my whole life. At least it can’t happen twice. My heart can only break like this once.

My emails from Monday were filled with dazed, shaken people trying to process it all and give and receive comfort somehow. Lori told me she was still in total shock, but feeling ok until another text/voicemail came in from friends and family offering condolences again. She asked me how I was doing. I replied:

“I’m just… numb. My face hurts from crying. We are all experiencing the same weird thing: that all of our friends, near and far, close and acquaintance, are contacting us today to ask if we’re ok. We’re not.

London is in mourning. I went to Heddon St and read the tributes, the flowers on the spot where Ziggy was photographed. I think Jake and Leah and I will go to the mural in Brixton tomorrow. TV is wall to wall. His beautiful face everywhere. I can hardly take it…”

On Tuesday we went to Brixton in the evening and joined a huge crowd paying their respects. People crying and singing, putting down photos and flowers and signs and holding each other. It felt good to do the same, though I do remember saying ‘I can’t believe we’re doing this’, as I looked at the flowers and photos. The next day I went into work at a client’s office and took breaks to have a little cry as I was working alone in a conference room. I did some writing the day after, a letter to Uncut about him, which was their lead letter in the next issue (it was good, heartfelt; I knew they’d print it). Friends had already started getting Blackstar tattoos by this point and I decided I was going to do the same. As soon as I saw the album cover in November I knew it was a brilliant tattoo idea and I resolved to get it done one day; I just didn’t realise I’d be compelled to do it so soon. It helped to obsess about it over the next weeks. After a few days I tried to listen to Blackstar, because I knew he had designed it for us, to help us mourn him. That was its purpose, it was like a puzzle with a missing piece before then and now it made sense. That Saturday we had a wake of sorts at a bar in Kings Cross. Songs were played and rivers of tears were shed. A few weeks later I got the tattoo, the five partial (well, four partial, one complete) star pieces, with a little Aladdin Sane flourish – blue and red halves, separated by a lightning bolt – in the second star. Frankly, it’s the least I can do for this man who changed my whole life. Who gave me so many people and so much music. This man who I will need and love forever; this man who is part of my DNA.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The tributes have kept coming and, in all honesty, very few of them have provided any comfort (though perhaps their purpose is to give that to the writer, not the reader). I didn’t want to hear what anyone said unless they actually knew David Jones, not Bowie, which is why Gary Oldman was great at the Brits. There was also a brilliant roundtable interview with Gail and Mark Plati. I’m still processing it all. You have no idea how much you can miss a person until you have no choice. I don’t love his music more than before, I loved it to the maximum while he was here. I’m grateful for the sheer volume of stuff left behind but it’s never going to feel like enough, and I don’t care about the vault right now. Knowing there are treasure troves of unreleased stuff is not going to make this better. I go through periods of listening to Blackstar for a couple of days and then not for a couple of weeks; I have to be in the right mood because it still has the capacity to make me cry (especially those last two songs, they’re too much), and maybe it always will. It’s strange to hear people talk about him in the past tense, and to think that younger fans will never know him as someone who was alive; to them he’ll be like Elvis or Kurt or Jimi – a dead rock star. They’ll never see what I saw, or live through him being present and releasing music. He’ll not accompany them on their life’s journey, like he did with me for over 30 years. My constant companion, who was always there by my side.

I learned that grief is a state of being when I lost my mum. I was truly knocked sideways by how much I missed her, how much I continue to miss her. I have endless capacity to pine for her, to wish I could tell her about a cool thing that happened to me or email her a link that made me laugh, or talk to her on the phone about these new Dylan-does-Sinatra-standards albums, which she would have loved so much. You don’t ever get over losing a parent, or in this case a cultural parent, if you like, which you could say Bowie was. You just figure out how to fold the loss into your life. In his case, I didn’t know him so it feels different; I didn’t give him anything, or ever talk to him, I just took what he gave me, the messages that he sent. I’m still getting used to him not being here, as we come up to our annual BowieNet party in July. He sent us little notes three years in a row, which was lovely, and which he absolutely didn’t have to do. I think it kind of tickled him that we’d get together and get drunk and party and listen to his songs (and raise money for charity) at an annual knees-up. Those messages made it feel like he wasn’t an ocean away. Now he feels an endless distance away. The transition period is bumpy but it won’t always be like this. Soon he’ll be a memory; his story has ended. The only thing keeping him alive is us. I watch videos now, gigs on DVD and bootlegs, and he looks so… alive. It’s strange to see that guy performing and get that hollow feeling, that knowledge of him not being on the earth anymore. No longer sitting in New York watching the same stupid You Tube clips we do and laughing, getting to hear new music every day, getting excited about what’s coming next. Just… life.

We should all aim to leave an imprint. So when we’re gone we won’t be forgotten. For most of us that’s just to our friends and family, they’re the only ones who’ll remember us. By talking about us when we’re gone they won’t forget us. It’s a somewhat bigger achievement to be loved and remembered by millions, way beyond your own close circle, but he was a unique, special man. He’ll be loved and remembered for as long as people play music.