Moonage Daydream

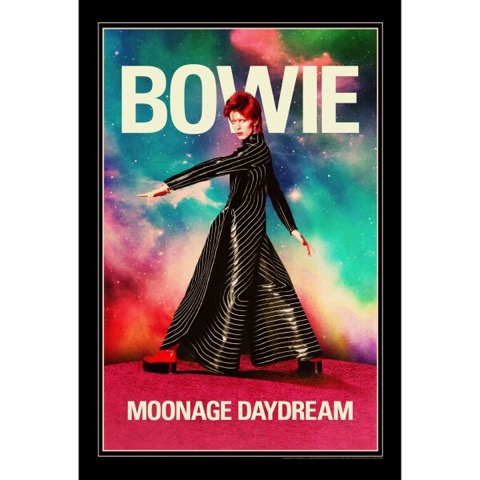

In early September, I saw Moonage Daydream at its premiere at the BFI Imax in Waterloo (followed by an amazing after-party at the Blavatnik Building, part of Tate Modern, where we danced to Bowie with Eddie Izzard: life level unlocked). Hearing too much about a film can be trouble. Trailers and reviews give you inklings while you try to avoid spoilers. But this film, which has been called an immersive (boy, is that an overused word) documentary, I’d already seen most of, so it felt organically like I had to prepare my thoughts and expectations in advance. I’d decided that the absence of much new footage, which friends rather than reviewers told me about, wasn’t going to bother me, but that turned out to be easier thought than done and not even the biggest problem with the film, ironically.

Its creator, Brett Morgen, had been courting hardcore fans for months. The early discussion last year about the film in the press continually said that it was based on ‘thousands of hours of unseen footage’. You might, then, expect quite a bit of it to be in there. Before Moonage even had a release date, much of the narrative said stuff like: ‘While exact details about the new Bowie film are scarce, unseen concert footage is supposedly a central element to the documentary’.

Perhaps this mixes up the difference between ‘unseen’ and ‘rare’ (pretty basic for a director to know the difference you might think) because at no point was this big fat selling point disavowed by anyone to do with the film. Wait for it, surprise coming up, it turned out to be a complete lie and there is very little new stuff; I’d estimate about 5 per cent. The film’s major find is some footage from the Isolar II Tour, shot at Earl’s Court in 1978. We get all of “Heroes” (though the first half is audio only, as we’re stuck with seeing fans coming in, for some reason) and a bit of Warszawa. There’s a little bit of Diamond Dogs Tour footage, too. But that is it. In a recent interview with the Guardian Morgen said ‘if you’re a hardcore aficionado, there’s enough new material to satiate you’. *turns to camera* *eye-roll*

He also said Ricochet was his ‘holy grail’ when giving a story to Indiewire of finding it like he was Indiana Jones. It’s one of the extras on the Serious Moonlight DVD and is not hard to find. It’s not a big treasure. It’s some ‘stranger in a strange land’ footage of Bowie going around looking vaguely like a colonial ruler, bowing his head to foreigners. As always with him, it is well-meaning but it shouldn’t have been excavated here as the heart of the film. It’s nowhere near that interesting. But Morgen loves Ricochet so much he repeats the same footage of Bowie going up and down an escalator three times to hammer home his point (it’s not the only reused, repetitive footage). One assumes the point was Bowie at his best making music when he was searching for something. Then when he found it (the wife) he became so contented that his music went bad. Good grief.

Morgen had discovered all this material after spending five years sifting through the vast Bowie archive (made up of some 5 million ‘assets’). He was only the second party allowed in there, after the V&A curators. Francis Whately did the BBC’s great Five Years docs, but going by this interview I don’t think he had access officially, though the estate were helpful (and Bowie was alive when he started, so it was different). I don’t doubt Morgen’s love for the music and his intention – to show the world why we’re all so devoted to Bowie – is pure. He obviously loves David very much.

But despite what he says, Moonage is not for fans; it’s for everyone else. It’s a Bowie gateway for people who are coming to him relatively fresh and, at a basic level, it does fulfil its aim. What is better than seeing a massive amount of Bowie footage on a gigantic screen? That’s always a good time. There were things I liked about it, such as the voiceover narration, which uses Bowie interviews spanning decades; that worked very well. Particularly insightful were clips from the superb Mavis Nicholson interview), recorded in 1979. It set the context well of where his life was at age 32. If he came off a bit cold or distant emotionally in those 70s interviews, that’s because he was. And therein lies the problem. So much of the film’s narration is based on early interviews, when he was just as stupid as any of us are at 26. Morgen tries to balance the interviews out by using more recent ones, when Bowie’s older, wiser, more aware of his place, and has a deepened understanding of his creativity and process. But it’s not enough. And worse, all the interviews were utterly humourless. What? David Bowie was a funny man, with a super-dry sense of humour. Using all these interviews to make him sound incredibly pretentious achieved what? Sometimes he was pretentious, nothing wrong with that. But you’re cutting off half a personality by making your film so po-faced, by believing the audience doesn’t deserve even one laugh as it’d break the mood?

Having said that, I am grateful that the film has a short section on his paintings, as it’s overdue for that aspect of his artistry to be taken seriously. Another part on Bowie’s half-brother and his illness, and his mum keeping her own emotional distance, was well-handled. The Russell Harty interview is a hoot, because he is just so incredibly weird compared to what English culture was serving people in 1973. The best-selling single of the year was the jaunty kitsch pop of Tony Orlando and Dawn’s Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree. On TV it was the era of The Benny Hill Show. The most-watched TV broadcasts of the year were Princess Anne’s wedding, then Eurovision. It is impossible to overstate how the nation would have dropped its dinner when they saw this guy who looked like he’d just got off a spaceship from fucking Mars. Harty, who was deeply closeted, sneers and goads him over his bisexuality for the audience’s amusement yet Bowie’s relative innocence and charm survives the assault. Kids who loved him back then were beaten up at school and called homophobic slurs. Being a Bowie fan was dangerous and these clips are important to show you just why. The film doesn’t pretend any of this didn’t happen and handles his sexuality well, which I appreciated.

Moonage’s aim is to give a mainstream audience all the information so they can fall in love with him just like we did. That’s a highly valid idea for a film! But, how dull, nearly all of the material is derived from the 70s and early 80s. There is a bit of him looking hot and inspired while covered in paint on the 1995 set of Hearts Filthy Lesson (which we don’t hear), but it’s in the film three times. There’s some collaged, thunderously loud versions of Hallo Spaceboy live in 1996/7, which I enjoyed. There is a nice juxtaposed Space Oddity of old with the 1997 NYC birthday concert. There are also some great bits of the Louise Lecavalier dance footage shot for 1990’s Sound + Vision Tour (but without any context, because it doesn’t fit the narrative, more of which later). We get about a minute of the ritual footage from the ★ video, without Bowie in it, which doesn’t make sense without context either, then we see about five seconds of him. There’s a little bit of soundless footage from a Reality promo to, I assume, compare young with old (if 56 is old). But that is it for anything after 1987. All this might take up perhaps ten or 15 minutes of the 2 hours and 15 minutes running time. Slim pickings.

It all means that we are subjected to the deeply boring reiteration of the late-work cliché. What I mean by that is the untrue and insulting idea that Bowie’s great music was over after 1983 (if not 1980). The other week in the Sunday Times, Morgen gave an interview in which he said that when Bowie met Iman in 1990 his work ‘plateaued’ [‘reached a state of little or no change after a period of activity or progress’]. How can he think that? The same paper printed a ‘ranked from worst to best album list’ that has ★, elevated because it’s ‘rich in symbolism’ (i.e. they consider it tragic), as the only album in the top ten made after 1980. 1. Outside is placed at 20 out of 26 (the Tin Machine albums are excised but the band is called ‘excruciating’). Look, I can understand why Morgen believes the general public wouldn’t want to watch a film that includes more than a small amount of the later work of the 1990s and the late work of Heathen onwards. The media has been ripping Bowie’s mid-career work (1984-99) to shreds for nearly four decades. Wasn’t this an opportunity to say, ‘Hey, the media has told you his 1990s output was shit, but it’s not!’? Morgen has repeatedly, openly disrespected that work in interviews. Then he backtracks on Twitter and says he loves ‘Heathens’ [sic] and Outside’? Not convincing. There is nothing in the film from Heathen by the way, a significant work that doesn’t fit his Bowie-got-boring-when-he-got-married narrative. And nothing of another important album, The Next Day, which is bonkers. Even back in his beloved 70s, there’s nothing from Young Americans and, from Station to Station, we get a minute of Word on a Wing accompanying a cringe photo gallery of Bowie and Iman, then ten seconds of the title’s track’s train sound! Very bizarre. Why not do a classic final ‘comeback’ section? Tell me a third act where he returns in his sixties and then dies a couple of days after his masterpiece comes out wouldn’t be a perfect ending to the film?

T

Thank god at least that the format isn’t one of those boring talking-heads documentaries. I don’t want to watch people who interviewed him a couple of times, or never met him at all, or ‘famous fans’ making their money out of speaking his name. I’m bored of that, aren’t you? In the last decade of his career he let others speak in his place and it worked, it was smart. But now he is gone. So those who chase that ambulance… I don’t want to see anyone churn out the same old anecdotes or stale cultural opinions for the hundredth time. I don’t dig it. I want him. I want him to speak and sing and be heard and seen. I want more analysis of his music and fewer people talking about his ‘influence’.

Moonage is about getting a new audience to understand the essence of who he was. It’s about young people going to see it and being blown away because it’s all new to them. Bowie is the music not even of their parents, but their grandparents, now. The music of my grandparents was Mario Lanza and Frank Sinatra. Falling generationally in between crooners and The Beatles was Elvis, a grand hero of Bowie’s. When I was young, in the early 1990s, Elvis was long gone, from 30 years before, full generations ago. Not even my parents were old enough to be his fans. Another 30 years has passed and now Bowie is to teenagers what Elvis was to me. I knew the real, beautiful, non-tragic Elvis because my mum and her best friend showed me all the 50s footage and some of the better movies. I didn’t know what happened to him when I was young. But most people did and made jokes about him. It was unfair, Elvis deserved better than to be remembered as a fat Vegas act who made dozens of bad movies. And so as Baz Lurhmann’s eccentric, flawed and brilliant Elvis biopic starts to leave cinemas, having completely captured how he filled the world with electricity, so arrives this film that should fill new people with the same wonder. It probably will, if you don’t know very much about Bowie. That Elvis film injects you with a thousand volts of power and energy and magic; it makes you see why, as Lennon said, before Elvis there was nothing. It manages to be kind of a bad film and a work of art at the same time. I craved for Moonage to do the same. But Morgen is not Luhrmann, he doesn’t have his talent.

A moment on the crime of using blurry footage. Morgen’s insistence on it being in Imax is a nice idea in its ambition. And some footage – D.A. Pennebaker’s Ziggy; the 1978 clip of “Heroes”, the highlight of the film; a bit of the Jump They Say video (no audio, too 1990s), the b/w S+V footage, the 1. Outside painting – works blown up to that scale. But a lot of it doesn’t. There are significant sections that are impossible to see properly because it’s all so grainy and of poor quality. It is unforgivable to put newly discovered Diamond Dogs Tour footage on screen that is virtually unwatchable. There’s a bit from the Station to Station Tour that is significantly worse than the cheap bootleg I have of it – and worse than was seen in the end credits of the first part of the BBC’s Five Years documentary (which trumpeted its ‘wealth of previously unseen archive’ and delivered on it). I’m embarrassed for Morgen. Even Cracked Actor was a mediocre transfer, so was the Serious Moonight Tour footage, so was Glass Spider. Just put the film on Netflix, it’ll look better. This was discussed after my second viewing with an expert (hi Andrew!) and he told us it was because of the differences between what is shot on film (transfers perfectly) and what is shot on video (transfers terribly, cannot be improved). In that case, why use bad, grainy footage at all? It just makes your film look amateurish. Just be honest and say it’s not good enough to be blown up to cinema size.

The first half hour was quite dull, because Ziggy is not my favourite period, but it felt like simply sticking Pennebaker’s great movie on a big screen. That is okay I guess, I’m happy to see Bowie footage again, big and loud. But song after song? By the time we got to the video of Ashes to Ashes looking worse than any bootleg I’ve seen, I had given up. Use my Best of Bowie DVD, mate, it’s better than whatever source you found. In the mid-80s, yes, I get it, he was unhappy. But to set up the high camp of the Glass Spider Tour as the lowest point? Playing only video from it, no audio, no context, was low. Play his entrance in Labyrinth to, what, sneer at a film that created a massive new generation of Bowie fans? Ignore Tin Machine like it never happened, despite its great importance to him as an artist, because it doesn’t fit your narrative? There can’t have been rights issues over all of it. And putting in the Pepsi ad proved what? It’s a bit of fun. This film is so painfully serious, it shouldn’t have been. It all continues to pour fuel on the idea that Bowie had ‘bad years’ without taking a second to look again and see if there is much of value. He just keeps refusing to expose the audience to anything from after 1983. We hear Spaceboy and a bit of ★. That is it. Not one more second from the last 33 years of his career.

I’m not a fool, I know this is a fan’s review. You can’t assess movies properly that way. It’s too personal. But when the director goes out of his way to appeal to fans, going so far as to make a trip to the Liverpool Bowie convention (I met him there, he was very nice), you’re saying that this is a movie as much for us as anyone else when it’s not. New people, and those who always liked him a bit and wanted to know more, should go on their Bowie journey and Moonage Daydream will help them do it. It’s why the film reviewers, who might like him just fine but aren’t mad fans, all gave it five stars (the music reviewers like it less). It’s why the audiences I saw it with adored it. But setting out that being with Iman made him boring/out of ideas in his artistic life jarred (feels like the estate insisted on her being dropped in). Never mind that he put out his weirdest fucking work, 1. Outside, three years after they got married. The estate are going to manage his legacy however they want following the end of the first five years of what I can only assume were his wishes (when great stuff like Glasto and Visconti’s Lodger remix came out, which he consented to). We have walked through that looking glass now. They’ve sold the songs to Warners for £125 million and now you are going to be told what to think about him. One recent ad campaign was a remix by the DJ Honey Dijon for the home exercise bike company Peloton, about which she said: “I chose Let’s Dance because it’s a celebration of music and movement – just like Peloton!”

I don’t think one person is going to realise Bowie is amazing because they’ve heard a piano-led, slowed-down version of Sound and Vision advertising the refurbishment of your spare room by B&Q (yes, this is a real example). I don’t think one person is going to buy some tat (socks, Barbies, cheap T-shirts, a Low tankard: another real example) and go, wow, I’ve just discovered Baal because of it! I want no part of this.

The film does have a purity of reach, because it takes his artistry and creativity seriously, rather than talking about his clothes or sex life, which is great. I just wish I could see the footage properly and there was some understanding of how he got better as he aged, rather than reinforcing a media-driven cliché of everything going downhill after the 1970s. Worse, setting up that the ‘peak’ we keep going back to is 1972. Are you kidding? His least musically adventurous stuff is the artistic pinnacle because of his impact? This legacy management is out of our hands, but we don’t need to buy into it. I’m disheartened that Moonage is such a disappointment. Not even just that, it’s a fucking mess. Of course, many fans will adore it uncritically because they don’t want to find fault, as this might be seen as a ‘betrayal’ of David. This film will bring about revelations for many and that’s fantastic. But that was not my experience.

I was hoping it’d become one of those documents that we would end up watching, a bit drunkenly, in excitement at its treasures, for years. I couldn’t even say I was looking forward to seeing it a second time. But I did go, because it had to be done. The first 45 mins of Ziggy is still boring. The middle section when we get to Berlin is a little better on second viewing. The incidental music choices are, repeatedly, Ian Fish U.K. Heir and The Mysteries (I guess he did get into my Best of Bowie DVD after all; that’s the menu music). And the last half hour is a dirty, offensive setup, lining up a bunch of great footage – Glass Spider, Labyrinth et al. – to tell the audience that he was shit in the 1980s. All set to a very on-the-nose Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide. We get it, he was great in the 70s, then he committed artistic suicide, then he got married and then he died. What a waste.

...

Stardust – 2 stars

Prologue

Between lockdowns, on a rare day in the office, I watched the trailer for the Bowie biopic, Stardust, drop on Twitter. Reaction was… uh… mixed. And that was just the trailer. A few reviews already existed, as it had been shown at American film festivals in the spring, so I read them: all the young dudes carried the news, and the news was not good. I knew then that I didn’t want to see it: I wanted to review it. In a display of entirely unearned confidence, I jumped up from my desk and followed the floor sticker arrows around to the desk of Phil de Semlyen, my colleague, the Global Head of Film at Time Out. I said, “Lovely Phil, how do you fancy letting me review the Bowie movie? Okay, I’ve never reviewed a film ever for any publication but I can do it, I think. And someone who knows the subject should do it anyway, so go on, let me! How hard can it be?” He said, “Sure, no problem. If I can do it anyone can!” Such a nice man.

Well, then. Slight panic. I did some research, made notes about technical things, then watched it on the Raindance website. Surely, surely, it was going to be better than early reviews said? Or, best-case scenario, those reviewers weren’t Bowie people and didn’t get it, and it would be filled with Easter eggs for the nerds. Why not? I’m an optimist by nature. Then I pressed play.

It became clear quite quickly that Stardust was, in fact, going to be even worse than the reviewers said. After about 15 minutes, hysteria set in; I couldn’t stop laughing at how bad the dialogue was. Then another 15 minutes passed, the laughing ceased and I started to get annoyed, because it wasn’t even bad in a good way. It was just terrible and humourless. And long. 109 minutes of my short life on this spinning rock I am never getting back.

But even if a film is profoundly bad, a review must be fair to the hundreds of people who worked hard on it. There is usually something to recommend it, to stop it from being a one-star. Stardust is not poorly made; the cinematography and other technical aspects are well rendered. But they alone can’t make for an enjoyable watch.

Also, what I didn’t entirely take in during that interminable viewing was the baffling decision to cast actors decades older than the people they’re playing. Obviously I knew that Flynn was a dozen years too old (when filming took place, last year). But Jena Malone (35 playing 22) looks young. I hadn’t given a thought to how old Ron Oberman must have been back then: he was 28, Marc Maron was 56. There was one scene with Bowie’s manager, in which the character was so primly English I thought it was Ken Pitt (49 in 1971). It was not. That was supposed to be the charismatic, cigar-chewing Tony DeFries, who was 28 in 1971: the actor, Julian Richings, who looks like Pitt and looks nothing at all like DeFries, was 64. That was so unclear I thought it was a totally different person! And on it went with the Spiders: Ronson’s actor was 42; Mick was 25. The guy playing Woody was 38; the drummer was 21. (Trev Bolder doesn’t even get an IMDB listing)

Why on earth would casting directors take out the young, vigorous heart of a biopic and fill each role with actors all far too old? I had only noticed Flynn at the time – the rest made so little impression that their various levels of decrepitude must have passed me by. I don’t believe the filmmakers didn’t know how old these real people were: they chose not to care. That’s the level of detail and commitment to reality we’re talking about here.

Anyway, my review was well-received. People told me it made them not want to see the film.

The version below is 95% the same as the original. I have reinstated a couple of bits I felt were important and dropped back in a few extra details for colour. I’ve also added links to provide backstory, which isn’t the style of TO’s Film section but no harm in adding here.

I’m very proud that I was allowed to write this review and grateful that I am Time Out’s person of record who gets to stand up to show and tell people what I know and think. This film won’t affect Bowie’s legacy or anyone’s feelings towards him. The gifted people who understand, who love him, who have something to say that’s carefully well-researched and cited, will continue to produce work about him that is credible and worth reading, watching and listening to.

_____________________________________________________________

Rock biopics that don’t have rights to the artist’s songs can work, as seen in England Is Mine (Morrissey) and Nowhere Boy (John Lennon) – but both were set in their subjects’ late teens. In Stardust, we meet 24-year-old David Bowie (played by 36-year-old Johnny Flynn) in 1971. He’s on his first US trip, promoting his Led Zeppelin-esque third album The Man Who Sold The World, presented here as a hard sell because he wore a dress on its cover (though Americans wouldn’t have known this, as the US cover was an odd cowboy cartoon). You need to believe this young man becomes one of the greatest rock stars of all time. You won’t.

The disastrous Bohemian Rhapsody was, by a (moustache) hair, saved by the music; no such luck here. Bowie’s estate, it turns out wisely, denied use of his songs. Then a one-hit-wonder with Space Oddity, Bowie tries to behave like a star before he is one, but is written as a boring, pathetic, hippy rube who misses every opportunity his publicist (Marc Maron, always watchable) finds. How about a modicum of research? David Bowie was ruthless, camera-ready, bright and funny, with megawatt charisma and unshakeable self-belief. Here he’s an unengaging wet failure, tortured by fear of succumbing to ‘madness in the family’. The severe mental-health problems of his half-brother Terry, seen in flashbacks, are treated crassly. While his wife Angie (Jena Malone) is a hectoring presence that doesn’t credit the significant contribution she made.

Flynn, who does a decent job singing songs that Bowie covered by Jacques Brel and The Yardbirds, works hard with a weak script. And Stardust does try to call some truthful Bowie bingo numbers: a song by one of his early heroes, ’60s singer Anthony Newley, plays on the radio; there’s a nice touch showing a recreation of his screen test at Warhol’s Factory; we briefly experience the bizarre tale of Bowie spending an evening talking to Lou Reed only to find out later he’d met his replacement, Doug Yule (according to Bowie’s version of events he never knew but Yule says he explained Reed had left the Velvets months before); and he wears that dress for a hopeless Rolling Stone interview – though the film erases his bisexuality, which is poor stuff. But this biopic can’t sell the idea of his progression as a songwriter because it can’t show us that he wrote Life on Mars and Changes around this time.

Ultimately, Stardust doesn’t work on any level. Not having his original music means it can’t truly let go, which makes this Bowie nothing close to the magnetic performer he was, despite a reasonable finale (with a Ziggy hairpiece that’s the wrong colour and inaccurate make-up). Because the songs aren’t here, his music is forced into becoming entirely unimportant, which is criminal. This film adds nothing interesting to his story. You’d be a great deal better off seeking out Todd Haynes’s gorgeously camp, self-aware, fairytale Bowie biopic Velvet Goldmine – it’s much more fun than this.

...

Led Zeppelin :: Celebration Day

Led Zeppelin never did get a proper send-off. I suppose there’s Knebworth ’79 , with a bloated, but still brilliant, John Bonham behind the kit. That was his last stand, certainly. But by then Plant had grown up, discovered irony and started to parody his own Golden God ridiculousness. Knebworth was good. It wasn’t great. Let’s not even go there with Live Aid (Phil Collins was the drummer). Then, to honour their mentor Ahmet Ertegun, who had signed them to Atlantic after hearing one demo, they did reasonably well, with Bonzo’s son Jason on drums, at the Atlantic Records 40th anniversary do in 1988. A couple years later they all jammed at Jason’s wedding. Seriously. And that was that. Until Ertegun passed away and, for his charity foundation, they agreed to do one big show at the O2 in 2007.

It’s been felt that Plant is the one who has moved on most successfully, professionally and personally. He’s a clever and engaging man, a blues scholar, a country bluegrass singer, a wonderful interpreter of song , and a hundred other things including a very private fella (so would you be if you’d had kids with two sisters in different decades). But this show, this one night, was his last chance to just drop it all and say ok, I give in, I’ll shake my mane and tilt my hip and play the part all over again. Everyone who attended went crazy about how good it was and then that was that – a DVD was expected but never arrived. Everyone knew it was recorded so what was the problem? Well, anything that has the Zeppelin name has to be perfect, and every fan knows that. It’s why their Live Aid show was kept off the box set. It’s why Plant refused to let half of his performance at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert go onto the DVD. That’s how they are. So what a shock when, a month ago, it was announced that, five years after the O2 show, it was coming out on DVD and in the cinema. Cue fan frenzy. I had to go and see it on the big screen. I’ve just returned and I’m waffling because I don’t know how to begin to describe this overwhelming, extraordinary musical experience I’ve just witnessed. I should say that I had a bootleg CD of the show the day after and a bootleg DVD the week after so I knew the content. But seeing it properly fixed up, on the big screen: it just knocked the wind out of me.

Right from the start – Good Times, Bad Times, track 1 from their 1969 debut album – the band crowd round the drum riser, and they barely move from that central square throughout. They’re connected, in a way that very few musicians are, and every nuance, every note, every smile, every single aspect of the performance is utterly, completely, inevitably and beautifully perfect. Every band member is on his own personal journey. If Bonzo himself were alive there’s not a chance he’d have been as good as Jason was that night. His powerful, muscular, frenzied energy powers the entire concert; he’s the rock on which everything builds from, and it’s clear how much everyone else relies on him to provide that explosive foundation, as strong as the one his dad built those 40 years ago. Listen to The Song Remains the Same and tell me that he doesn’t outdo his old man with ease. Listen to Kashmir and try not to feel your spine bending with those thunderous bass drum kicks. And listen to that final flourish in Rock and Roll and you’ll know in that moment that not a drummer on earth could have done it better.

John Paul Jones, then aged 61, has carved out a rather fascinating career as a collaborator, with the likes of Diamanda Galas and Brian Eno, and as a producer/arranger, most notably creating the gorgeous string parts on R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People. After this show he found his taste for playing live again with Them Crooked Vultures but at this performance he’s a serene, anchoring presence, though I could have stood to hear his bass a little more crisply in the mix. He comes into his own on keyboards and organ on a flawless No Quarter, fluidly nails the lovely melody line on Ramble On, leads the show during Trampled Underfoot, and what a pleasure to hear that bass run on the big finish at the end of Dazed and Confused. He and Page have an almost telepathic connection, two old stagers butting heads and grinning at each other when they know they've hit a perfect moment, when everything has gone just right.

Jimmy Page, then aged 63, is looking a little haggard these days, but so would you if you’d lived the life he’s had. There’s a reason that kind of guitar playing died out – surely looking at those scrunched up faces just got too funny after a while. In a way he has the hardest job of all, because he’s not played these songs, or indeed any songs, on stage regularly since the band broke up. He turned up for Plant’s 1990 Knebworth Festival encore , and reunited with him for a quite brilliant 1994 TV special for VH1, followed by two well received tours together in 1995 and 1998. But on the whole you know he’s the one who’d most love to be that guy again. The one who is the least creatively satisfied with what he’s accomplished in the last few decades. (Whisper Coverdale/Page if you dare.) He just wants Plant to be his guy again. And there’s no way he can play like he did when he was 25, just as Plant can’t possibly sing like he did when he was 25. But with all that said, he delivered one of the performances of his life. Not every note was perfect, not every run was as fast as it used to be, but he put every single shred of himself into that performance – from riffs to solos to violin bows to a bit of Theremin, it was all there. And he got better and better with each passing song, as if he was finding inside himself some internal clock that he was able to force backwards.

Oh Planty, Percy Plant, the former layer of tarmac on the road to West Bromwich. The Golden God (age at gig time: 59). The man who survived the 80s, somehow, to go on and win the Grammy for Album of the Year . The man who launched a thousand utterly terrible copyists. The man who shook his luscious blond hair, wore the tightest pants in rock, stuck his bare chest out, and howled like the hammer of the Gods was upon him. He has so very much to answer for. It all rests on him, truly. The band played like demons and shook the foundations of the venue, the cinema and my aching, bruised head (I fell off a spaceship the day before, but that’s another story). The groove these guys got going behind him was out of this world – no pressure then. But which Plant would turn up? The one who’s barely bothered to look back to those days, to his credit? Could he just shove it all aside and play that role for one night only, for the last time ever, and not ruin it by winking or getting the tone wrong? He had to be the last hold-out, the last person who wanted to do this, but he was doing it for Ahmet, not for himself. So he just stepped out onto the stage and, like an actor playing a classic role in his twilight years, he howled and preened and nailed the shit out of the songs. He took it seriously, finally. Not the songs themselves, after all, half of them are about rescuing maidens from castles or climbing mountains dressed like Gandalf, but the music. The sound, he just used the noise itself to push his performance to the limit. And, like Page, he just got better song by song and, being as smart as he is, he knew what to hit and what to leave. He knew which songs to excise (no Communication Breakdown or Rain Song; too high, they’d sound wrong sung lower) and he knew which moments to let go. He’s no fool: there were notes he’s a mile away from being able to hit so he used his voice, as he has been doing for the last 20 years, very cleverly and gained power and confidence with each passing minute. He’s still snake of hip (if not of jowl) and manages to exude sex almost every minute he’s on stage. And blow me down, he truly looks like he’s enjoying the night, getting off on every second and the camera captures some wonderful moments of exchanged ‘we’re really doing this!’ recognition and affection between him and Page.

They turn to Jason often, and these precise, insanely powerful songs just come at you in waves. It’s actually highly moving, seeing these four people on stage side-by-side. And that’s why they should never do it again – because it was so perfect. I hear people say that there are no bands like Zeppelin around any more. And perhaps it’s good that the more bloated bands of that ilk are long gone. But I tell you what – there were no bands around like Zeppelin even when they were around. No-one could touch them. They were out there on their own for so many years. And that’s not bad considering that I can’t tell you what a single song lyric is about. It’s the sound, it’s the interplay, it’s the alchemy – man for man, Zeppelin are the best rock band there’s ever been. And that holds true in 1969 and in 2007. I used to say that, if I had a DeLorean, and I could go back in time for certain gigs, I’d choose a particular bunch, like Bowie at the Hammersmith Odeon ’73, Hendrix at Monterey ’67, and a dozen more. And then I would always add to that list, Zeppelin at Madison Square Garden July ’73, aka The Song Remains the Same concert film. But now, today, right this minute, I’m taking it back. That night, December 10th 2007, is the one I’d choose as the crowning night of their career and the one I’d have given anything to attend.

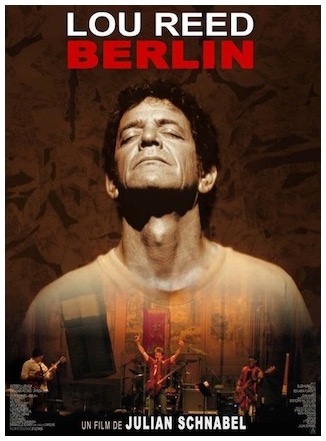

Lou Reed, Berlin

Once Dylan had shown the way, that you didn't need a sweet crooners voice to get records made and sold, artists like Reed found themselves with a future they could reach. In remaining true to himself and releasing the bleak Berlin, a tale of drug addiction, suicide and depression, a theatrical almost rock opera, he destroyed his own chart-bound career singlehandedly. Produced by Bob Ezrin - best known for his heavier rock work with Alice Cooper and Kiss - it was a shock to the system and, with reviews mixed and sales sluggish, Reed and Ezrin abandoned plans for a stage interpretation of the material. It was a forgotten record. At that time, Reed hadn't even visited Berlin. As years passed the maligned album was rediscovered and anointed a misunderstood masterpiece. Indeed, one can only imagine the effect it had on Bowie at the time who, three years after the albums release, fled to Berlin to escape his own addictions and found the inspiration there in person that Reed had found in absentia.

At the end of 2006, these dark, orchestral songs found their way out of the dust and into Brooklyn, Reed's birthplace. An idea to perform the entire album with the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, brass section, backing vocalists and a collection of acclaimed musicians had come to fruition. Over five nights at the tiny St Ann's Warehouse, artist turned film director Julian Schnabel filmed the performances, staged in front of his own set design.

The film starts with Schnabel's brief on screen introduction, welcoming the audience and Reed's mother and sister to the show. Then the band, including original album guitarist Steve Hunter, take the stage, as the lights swirl. Hunter sports a beanie hat, Zappa-esque facial hair, glasses and a crooked toothy grin that remains on his face throughout the film. His playing, perhaps the only mainstream aspect of the performance, dazzles throughout. The songs are staggering in both their complexity and simplicity. Behind the band is a screen playing the story of the album's protagonist Caroline, played by French actress Emmanuelle Seigner; beautifully shot by directors daughter Lola. The dramatic scenes linger over the music, overseen by original album producer Ezrin and Hal Willner, wrapping around the story. But the camera lingers on Reed - as inscrutable as ever, but allowing himself a few stolen smiles. Berlin might be his masterpiece and he knows it. This film is no Shine A Light. There are no rich bankers and their young girlfriends in the audience, whooping as they hold their sponsored beer holders aloft. The deep lines on his face are all that connects him with that world. He trades guitar lines with Hunter and vocal lines with perfect guests - backing vocalists Sharon Jones and Antony Hegarty.

This assault on your senses comes to an end with a searing take on Rock Minuet, from 2000's Ecstasy. Going further back than the film's subject, Velvets classic Sweet Jane plays out over the credits. This film is masterful; it puts you not only in Brooklyn on those December nights but also sends you to 1973 - where a future of certainty was rejected for something from the dark heart.

Berlin, opens July 25 2008.

http://www.berlinthefilm.com/

...

Shine A Light

In 1990, when I was 13, the same age as mum was when she saw them first, she took me to see the Stones at Wembley Stadium. As I gazed upon Keith's weatherbeaten Sid-James-looking visage I knew this band would be with me my whole life. I didn't anticipate growing up with them as mum had but that's what's happened. They are, arguably, now a better band live than they were 20 or 40 years ago. I put a fair bit of this down to the recruitment of the masterful and solid bassist Darryl Jones (born the year before the first Stones single Come On was released), who earned his apprenticeship playing with Miles Davis at age 22, which must have been quite a baptism. He gives the band a kind of grounding that they've never had before and Charlie seems more at one with this jazzman than he ever could have been with Wyman. I saw the Stones live again in 1993 but not since - I simply can't blow a hundred quid on a bad seat in a stadium, on finance and principle. I have a wealth of material at home on film, though nothing compared to a real Stones collector of course. But from 25 x 5 (VHS only, it's never come out on DVD) to the Double Door to Four Flicks, Bigger Bang, Gimme Shelter, Sympathy for the Devil/One Plus One, Cocksucker Blues and more, I've got the cornerstones of their career to hand, the visual markers by which one can trace their history. I will soon add to that the tremendous concert film Shine A Light.

There is no other filmmaker who understands the Stones as Scorsese does. Mean Streets, Goodfellas, Casino and the Departed all featured their music to great effect - Jumpin' Jack Flash in the first, Gimme Shelter in the others. And with his recent masterpiece of Bob, No Direction Home, he was the only choice to capture this small show at the Beacon Theater in New York. It's essentially a live concert film with a number of interwoven news clips of them being asked the same dull questions about how long they can keep on going for going back to the 60s. These clips are comical, provoking much laughter from the audience, especially in response to Charlie, ever unimpressed and nonplussed by the swirling circus around him. As you watch it you realise what odd lives these four extraordinary Englishmen have had and continue to have. Mick is the businessman, he was ever thus. Keith is on a constant quest to bring out the sincerity from his old friend, knowing that the real Mick is in there somewhere. He stops Mick from becoming too much of himself. All the while practicing the 'ancient form of weaving', as they call it, with Ronnie, always the most positive, excitable, force of togetherness in the Stones camp.

Scorsese does a magnificent job with the limitations of what I feel was probably not the best venue to set the show in. A fundraiser for a Bill Clinton sponsored charity the show takes place in front of the kind of corporate crowd you might expect - businessmen at the back doing a self-conscious head-bob to the songs they know while their 20-something trophy girlfriends swoon adoringly on the front rows at this grandfather on stage, his perfect washboard stomach pulling focus. Dad and grandad he may be but every woman in that theatre would go home with Jagger without pause. Surely a knight of the realm has never shaken his behind so much? Mick is simply extraordinary; cheeky and charming, his voice as strong as it was before I was born, his powers as a frontman undimmed.

Because of the size of the venue and the need to light it effectively, it almost has the feel of a TV show rather than a gig, which seemed to be the band's fear before filming started. Scorsese's previous rock concert film, The Last Waltz, was shot in the cavernous Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, a venue wide enough to hide cameras in behind the band and, due to a spectacular set of chandeliers, easy to light without anything looking added or contrived. That was Scorsese's choice - you would only see the audience from the back of the stage for a few brief moments. Other than that, there were no audience shots at all, which put the viewer inside the gig. This Beacon show has altogether too much audience in it, though that's a minor quibble. What delighted me was the setlist. It contained, as it had to, some of the classics you'd expect to hear but also a fair few obscure album tracks. I jumped in my seat as All Down the Line and Loving Cup (the latter with a beaming and brilliant Jack White duetting) from Exile made their appearance. And the two ends - youth and experience - of the Stones spectrum made their bow too - exuding sex, as ever, was Christina Aguilera, doing a fine job on Live With Me. Their roots got the nod with the evergreen Buddy Guy on Muddy Waters song Champagne and Reefer. In the cinema I was surrounded by people my parents age, my age and kids in their early teens and younger. Their parents coughed nervously at "bring me champagne when I'm thirsty, bring me reefer when I want to get high" as I chuckled. I noticed the super filthy lyrics of Some Girls got a snip, which was to be expected I suppose.

Sheer energy carries the film along with considerable ease as band and filmmaker rise to the occasion and beat the venue. Mick in particular is on fantastic form, barely able to contain himself as he shows the trademark energy levels that put men a third of his age to shame. The camera spares no-one and rightly so - these men look in their 60s and they couldn't care less. There is no attempt to soften the lens, no careful shooting of the ravages of time. Every canyon-like wrinkle was proudly displayed on the 40 foot IMAX screen I was watching it on as the battle scars of decades of hard living came into view. Odd as it sounds, it's Keith's childlike joy that comes across clearest of all. On that famous face is a permanent grin, the sheer happiness and contentment coming from a man doing exactly what he wants with his life. A sensitive, passionate, warrior gypsy, Keith is the heart of both film and band. Against all odds, he is going to make a fine old man. His playing has hardly been better, as he says in an interview segment - "Both me and Ronnie as guitarists are pretty lousy but together we're better than ten others". Even the supporting cast have put in the years - sax legend Bobby Keys has been with the band since 69, keyboardist Chuck Leavell since 82, Darryl since 93, vocalists Bernard Fowler and Lisa Fischer since 89, keyboardist/guitarist Blondie Chaplin is the novice of the band having put in a mere decade of service.

In the 46 years since their first single, a Chuck Berry cover, they have seen off hundreds of bands and they are still standing. It's quite something when the definitive concert film of a band can be made when they're not at what is supposed to be their peak, the 1960s, but in fact when they should be collecting their bus passes. Mick once said that he never believed having a good time was something only for the young. But as they say, what else do they know how to do? Every few years the call that everyone expects will come and it's time to go on tour. Their back catalogue is unsurpassed and, as the sparks fly off in all directions, they can still deliver the best rock and roll show on earth.

...

I’m Not There

In 1966 my dad attended the famed 'Judas' concert. He was 15 years old and saw the truth in front of him as Bob Dylan snarled 'Play it fucking loud' to his Band; years later this iconic footage was discovered and shown in Scorsese's definitive Dylan documentary No Direction Home. Now the definitive movie about Dylan has been made. As an 11 year old, I watched and re-watched that Rolling Stone video until it was worn out. It was responsible for my first visual sightings of artists I have since become devoted to - Beatles, Stones, Doors, Zeppelin, Bowie, Joni, Hendrix, Prince, Neil Young, U2 and more. Without fail, I have grown to love almost every artist featured in that tape.

Half way through it came the moment my musical life changed forever. In the middle of a section about increasing commercialism in music, the new power of record companies and the bloated self-indulgence of supergroups like the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac comes a cheeky piece of Hopper narration - "In the mid 70s, Dylan went his own way as usual". The screen flickered into a live clip I later found out was from 76's sprawling Renaldo and Clara (partially filmed during the '75 Rolling Thunder Revue tour). His face filled the screen, his sloping Jewish nose, the white paint (clearly a reference to shallow Kiss-style rock) covering his face, his sparkling green eyes, a wide brimmed hat and the voice -

Early one mornin' the sun was shinin',

I was layin' in bed

Wond'rin' if she'd changed at all

If her hair was still red.

Her folks they said our lives together

Sure was gonna be rough

They never did like Mama's homemade dress

Papa's bankbook wasn't big enough.

And I was standin' on the side of the road

Rain fallin' on my shoes

Heading out for the East Coast

Lord knows I've paid some dues gettin' through,

Tangled up in blue.

She was married when we first met

Soon to be divorced

I helped her out of a jam, I guess,

But I used a little too much force.

We drove that car as far as we could

Abandoned it out West

Split up on a dark sad night

Both agreeing it was best.

She turned around to look at me

As I was walkin' away

I heard her say over my shoulder,

"We'll meet again someday on the avenue,"

Tangled up in blue.

Two verses only, that's all it took to mesmerise that 11 year old. I couldn't hope to understand all he was but I hoped to learn, to try and delve further. Now 20 years later I see that not understanding completely, not being able to pin down exactly what or who he is is central to everything. That's the tack taken by I'm Not There, the new Todd Haynes film. By accepting that you cannot understand Dylan, you gain a great paradoxical understanding of the whole. Dylan once said that he has always been 'in the process of becoming'. Haynes takes that and creates a fantastical, but sometimes accurate, approach and weaves a tale unlike I've ever seen in a film.

I saw I'm Not There at Xmas, with my dad and his best friend, a rabid Santana fan. Without realising, we were booked into a subtitled screening. It was distracting yet helpful in many ways, especially when it came to the lyrics. Seeing them written on the screen enhanced their power even more. I saw the film again yesterday, sans subtitles this time. The power of the film had increased yet again and I expect that to continue upon subsequent viewings. The film is 'inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan' and sure enough, not one of the actors present plays a character called Bob Dylan. The characters are composites of aspects of Dylan, his personality, his persona, his songs, his heroes and the strain felt by the expectations placed on him hovers over all proceedings.

Marcus Carl Franklin, a young black boy, plays Woody Guthrie. He represents the faker - the Dylan who told interviewers he ran away to join the circus when in fact he was having his bar mitzvah. In the film, Woody visits the real Woody Guthrie in hospital, something young Dylan did too. He's seen as a cute runaway, shilling the rubes with charm when he can get away with it. Christian Bale plays Jack Rollins, the Greenwich Village folk troubadour version of Dylan from 62-65 and then the Jesus loving Bob of the late 70s. Heath Ledger plays Robbie Clark, an actor who played Jack Rollins in a biopic but was taken over by the attention it brought - this character comes close to being 'family' Dylan, with his wife, the Sara (Dylan's ex-wife and the inspiration for Blood on the Tracks) of the piece, played by a delicate but resolute Charlotte Gainsbourg. He struggles with the balance of fame and family as his marriage crumbles and is portrayed as callous and self-absorbed.

Richard Gere, looking a touch too much like The Dude, plays Billy the Kid, as Dylan did in 70s western Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid. Ben Whishaw, a superb young English actor, appears talking to screen, facing possibly the draft board, and spouts the innocent, idealistic rhetoric of the 20 year old Bob in the name of Arthur Rimbaud.

Finally, in the flashiest portrayal, comes Cate Blanchett's twitchy, amphetamine-fueled Jude Quinn. The most recognisable of all the pieces of Zimmerman - corkscrew hair, shades, striped drainpipes, ever-present cigarette; in essence the Don't Look Back Dylan. The Newport Festival Dylan. The Judas concert Dylan. The Dylan under the most pressure, about to crack. Through the film, you realise that the weight on his shoulders would have been more than most could bear. While Dylan was not, by any means, the first musician to speak of social issues in songs, he was certainly the first pop star to do it. In a world of crooners and holding hands, his songs seared through the consciousness of young people on the cusp of a civil rights revolution and, as you might expect, that terrified the authority figures of the time. All the young men being drafted and the women watching them leave, who had been going to their deaths as part of the previously unarguable fate that befell generations before them, listened to this so-called protest singer with reverence. Dylan terrified the establishment, who had realised that a pop singer would and could have more influence on their children than any teacher, policeman, politician or parent.

As such, they set out to expose Dylan as a middle class mid-west faker who never believed in what he was saying - his abandonment of folk and embrace of electric instruments merely proved their point about the insincerity they were certain they saw in him. These detractors are created as a composite character - he's a journalist (Mr Jones, a manifestation of both the snooty English journalists in Don't Look Back and the eponymously named character in Ballad of a Thin Man) in the Quinn scenes and a sheriff in the Billy chapter (Pat Garrett, his famed nemesis) each time played by the same actor, the impeccable Bruce Greenwood.

Everyone wants something from these Dylan composites, more than they are owed. Those who dislike and fear him disrespect him. The fans expect too much; from the downcast folkies roaring their horror at electric Dylan (with a comic portrayal of the apocryphal Peter Yarrow story of chopping the power cables at Newport with an axe) to the wide-eyed teenagers seeing their Vietnam-scarred future as they glance desperately at him, hoping he'll show their path out. It's too much for one human being to cope with and the film splits him into the six distinct characters to recognise this. There is no Bob Dylan - he is a construct, a persona with many different aspects. In order to understand what is in front of you must accept that you can't understand him. You can absorb more from him if you deconstruct less. You must accept that, like the title, he isn't there.

It's one of the most audacious and ambitious films I've seen in a very long time. It was never going to be a Ray or Walk The Line. A piece like this allows each actor space to create their own version and vision of someone indefinable. In particular, Blanchett's Quinn is extraordinary. I expect her to be standing triumphantly on the Oscar podium soon because anything else would be a travesty. I am convinced that no other actor, male or female, could have inhabited this version of the man with such passion and knowledge. The music propels the film, as it should. The originals sit alongside covers by Tom Verlaine, My Morning Jacket's Jim James, Yo La Tengo, Stephen Malkmus, Calexico, Eddie Vedder and Antony and the Johnsons. Malkmus's wild mercury renditions of Ballad of a Thin Man and Maggie's Farm are worthy of particular praise.

I'm Not There is an overwhelming piece of work from first minute to last. For the first time you get a sense of the strength required to be Bob Dylan. A popular singer has never been more important, has never changed things so much and has never been required to be so saintly by the baying media hordes in order to be believed. It's impossible for one man to give as much as he is exhorted to give but no-one else was standing there on his level in the glare of the changing decade who had the ability, intelligence or vision to deliver. The establishment sensed cultural and political revolution and made Dylan their poster boy for it. And in a sense he was that figurehead since he fulfilled what both the journalists and his admirers wanted. They tried to tear him down but he is the one still left standing. He comes across as stubborn, dismissive, sometimes mean and sexist but above all he is unarguably a visionary, a great American icon but an imperfect person - with this film you feel Haynes has an understanding of Dylan I didn't think any filmmaker was capable of.

...

Ridin’ that train, high on cocaine

I'm always looking for the next great one to add to my collection, a great DVD package to add to my list. But what I never get to do (aside from Ziggy Stardust, twice) is watch them at the cinema. So, yesterday, I did both. I added a new movie to my favourites and got to see it on the big screen!

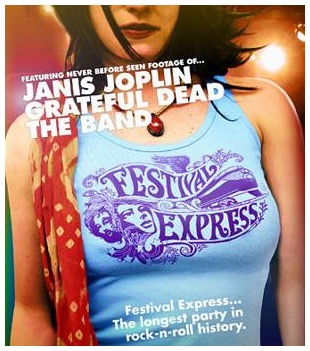

The movie in question is Festival Express. Directed by Bob Smeaton (the Beatles Anthology) this documentary is a combination of old footage and new interviews from the participants. The synopsis is thus: In 1970 a group of musicians played 3 festivals in Canada, travelling to each on a train. In short, they got on the train in eastern Canada and partied, sang, played, drank and smoked their way across the provinces to Ontario, Saskatoon and the final gig in Calgary.

As ever with these rock movies of the late 60s/early 70s it's part historical timepiece and part thundering concert film. This one differs from Woodstock et al because it contains new interviews with the participants, some recalling events with more fondness than others. In particular I'm talking about the misery of promoter Ken Walker, not the most likeable of guys in any event. The recollections of the musicians involved were wholly more happy and the image you get is of one long party, musicians trapped on a train for a day or two at a time amusing themselves by jamming. Oh to be a fly on the wall on that journey.

There were some acts I was looking forward to seeing more than others. I haven't seen much live of the Grateful Dead and was expecting a turgid set of endless soloing but I'm happy to report that was not the case, I really enjoyed their performance and the spectre of Jerry hangs over the film, he seems to be in almost every frame; big smile on his face, an intimate portrait of a much loved man. He didn't have a bad word for anyone and brightened every frame he was in. Janis Joplin is, well, Janis. There’s no-one like her and I was almost literally blown across the room watching her; there really are no singers like her left. Her style, a slight screeching vocal, can be challenging to listen to (especially in Dolby Surround sound) but her songs and delivery are what it's all about. She held the crowd in the palm of her hand, the Canadian audiences sat enraptured.

I was looking forward the most to The Band. I'm a huge fan of theirs and have seen precious little footage of them aside from Scorsese's rock masterpiece The Last Waltz. They played at Woodstock but were left out of the original film and the directors’ cut. They were never a glamorous band, they looked old even when they were young and hid the pretty-boy looks of leaders Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko as best they could. In fact Danko has a hilarious scene on the train with Garcia and Janis, later in the movie when, totally wasted, he tries to lead everyone in song.

Anyway, they got 3 songs in the film and I was in heaven. Aside from Levon Helm, The Band were in fact Canadian so these gigs were their homecoming. I could sit and watch this band for hours, but this film left me satisfied and rushing out to call my parents who see it in Manchester in 2 weeks. They're going to love it...

What a rare experience, getting to see a rock movie on the big screen, learning something new about each band and discovering a transcendent performance by another artist, Buddy Guy, perhaps the movie's highlight. The slightly bizarre presence of gold lamé clad doo-wop dancing troupe Sha Na Na (they were at Woodstock too for some reason) doesn't detract a bit from the film, in fact it adds a bit of levity.

That train must have been a cool place to be on - no sleep, just good company and good music. If you can see this movie, take the chance. Most of the great past musical events to be committed to celluloid have been discovered; this one could be the last great festival movie to be found.

http://www.festivalexpress.com

...