Paul McCartney – O2 London – Dec 19, 2024

“I can’t tell you how I feel, my heart is like a wheel”

Going to see Paul McCartney in concert is like experiencing the musical history of the twentieth century all at once. It’s a level no other artist reaches. The Stones do get close. They bang out the hits, have a looseness I adore and Jagger works harder than anyone. But he wants to go big, which means his band are always going to be long-distance dots in Hyde Park or a football stadium, which is nobody’s ideal way of connecting with music. Only Springsteen can make Wembley seem like your front room.

Dylan could reach that level, but chooses not to. He’ll ramble through seventeen songs and maybe three of them will be well-known. You’d be lucky to recognise any, even during the choruses. And he’s not going to thank you for coming with thumbs aloft either. (No shade, I just saw him twice and it was beautiful, but he is who he is; he doesn’t come to you, you go to him.) And sure, the heritage artists (a Who, a Stevie Nicks) have decent hits catalogues but they’ve only got maybe ten classic tracks at best, which they dot around the lesser songs that make exits for pints easy. Bowie was different. I wanted to hear his new stuff as much as I did Ashes to Ashes or what an arena audience would consider a rarity, but I don’t deny that when he played an older song that had become part of my brain pathways decades before, it did deliver a particular buzz.

But McCartney stands alone… He’ll choose around thirty-five perfectly crafted pieces of songwriting, with no limit to what he might drop in or leave out, from hundreds of options. His highly experienced band, all of whom are now in their fifties and sixties, are a huge part of why the show holds together, too – Rusty Anderson, Brian Ray and the great Abe Laboriel Jr. have been with him on the road for more than twenty years, with musical director Wix Wickens there since 1989. A great horn section gives the sound some heft as well. McCartney remains a superb bassist, and he’s not a bad guitarist either.

There is no trepidation, no fear of disappointment, before a McCartney gig because the night is about you as much as him. (This show was my fourth; I’d seen him on consecutive nights at Earl’s Court in 2003 and another time in Hammersmith, 2010.) Leah had never seen him live; before the show we were buzzing with excitement. We grew up with Beatles songs, hearing them in the mid-1980s… only about fifteen years since the band split, which is a little mind-blowing. Our parents were the luckiest people in the world to be there first time around. Her dad played these songs on the guitar, especially the early stuff. Always the dramatist, my mum played She’s Leaving Home, loudly and while weeping, in the record room as I walked down our avenue and off to university (I think she was pleased when I gave up after a year and came back).

Being in the same room as a Beatle is a joyful, surreal and moving experience. Two are gone, and neither of them particularly enjoyed playing live and didn’t do it that much. One is here but I’m not racing to hear Photograph any day soon, no offence, Richie (more of you later). You know what you’re going to get with McCartney, though he does throw in a few deeper cuts for his own amusement and avoidance of boredom. I do consider those tracks to be filler in the setlist, however. Though they are still songs other people couldn’t dream of writing, they are, for him, fairly second rate. I’m talking about stuff that is, you know, fine, like Junior’s Farm, Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five, Here Today, Letting Go, Dance Tonight, Now and Then (terrible video too; Real Love is much better). And My Valentine, written for his wife, Nancy, is the picture of mediocrity. (She’s the second New York Jewish girl he’s married, incidentally, and he doesn’t mind a visit to shul for Yom Kippur either, so I do forgive him.) And you have to give it to the guy on stamina: each show day he does a dozen-song setlist at 5.30pm for a ‘VIP soundcheck’ crowd, that’s some warm-up before the main gig.

After a beer or two, we took our seats – you could feel the emotion and anticipation pulsing through the venue already. The crowd had an age range of eight to eighty, which was gorgeous to see (it reminded me that my mum saw the Stones when she was thirteen in 1964, then took me to see them when I was thirteen in 1990). The pre-show mixtape was his own stuff, clearly set up to include songs he wasn’t going to play, like Flaming Pie and the terrific Coming Up, though they were ropey remixes. He certainly doesn’t mind reminding you how many songs he has to choose from. It’d be easy to create a setlist or two out of the crackers he didn’t play: Fool on the Hill, Can’t Buy Me Love (sometimes the show opener), Yesterday (!), The Long and Winding Road, We Can Work It Out, Silly Love Songs, No More Lonely Nights, I Saw Her Standing There, All My Loving, Eight Days a Week, Eleanor Rigby, Hello, Goodbye, Two of Us, Back in the USSR, My Love, Here, There and Everywhere, She Loves You, Michelle, Magical Mystery Tour, Paperback Writer and plenty more, including We All Stand Together, aka the Frog Chorus, and Penny Lane.

Let’s be real about it: in The Beatles, that great little guitar group, McCartney was the songwriting goldmine. And while the quality from George and John in the 70s was as high as his, the consistency was not. Seeing him live is your only chance to pay tribute to the whole lot of it, who they are and were, what it all meant and still means. So when you’re in that state of anticipation already, and the lights go down and the band thrum the endless, deathless opening chord of A Hard Day’s Night to start the gig, you are ready. And when you get that hit, your entire body experiences a WHOOSH that’s akin to, I don’t know, Neo learning kung fu in a split second, or Spock pressing his fingertips to your face and mind-melding the entirety of life in a breathless minute, or feeling the opiate ecstasy of falling through the floor in Trainspotting. And this feeling doesn’t happen just the once, no. It’s done to you over and over again for nearly three hours. It’s like going through the stargate at the end of 2001. At the end of it all stands a father of five and grandfather of eight, a quite smug, millennia-straddling musical genius delivering sounds you’ll be hearing in your head on your deathbed.

But the other thing about Macca, which I remembered almost as soon as the gig started, is that he’s not very… cool? As a bloke, he’s naff in lots of ways, which somehow makes him more endearing because he’s trying so hard to please you from the cheesy, decades-old speeches between songs to the cheap-looking visuals on the screens around him (great use is made of Get Back, though). He is very pleased with himself. A combination of a musical genius, a vaudevillian at heart and a career politician, he’s exactly aware of his effect on people. A man who knows how to put everyone at ease by being the person they want to meet. Bowie had some of the same persona, at least from the 80s onwards, though he was always more outré so it’s no surprise they weren’t each other’s cup of tea.

What McCartney is also understandably keen to reiterate at his shows is what you might call, “You know, I did do other songs after 1970!?” which puts fourteen non-Beatles songs in a setlist of thirty-six, though the Fab Four content does dominate as the gig gets into its latter third. Only one of the last ten songs – the eyebrow-singeing, pyrotechnic spectacular of Live and Let Die, always a highlight – is not a Beatles record.

The layers of emotion just kept piling up throughout the night; I hardly know how to talk about the encore without welling up. But first, there is the very fact of his age, which means his voice is understandably diminished, which in turn somehow makes the whole enterprise more poignant. When we’re old, I said to Leah, and we can’t hardly get out of our chairs in our seventies, we’re going to look back at this night where eighty-two-year-old Paul McCartney has just danced off the stage to greet his family after playing for nearly three hours and go: what the fuck? How did he do it? One day in 1957 he’s just a fifteen-year-old motherless boy from Walton singing Twenty Flight Rock to a cooler kid, trying to get into his band… and the next day it’s 2024, he’s craggy and grey, but trim and spry, on an arena stage making grown adults cry.

Having written songs across multiple genres, you’re getting everything from exquisite love songs (the hot, beardy Paul of Maybe I’m Amazed; while I’m here, it wasn’t just Yoko who was targeted for the crime of being a Beatle’s wife: I haven’t forgotten how abominably Linda was treated by the media and fans during her lifetime even though she put only positivity out into the world) to droplets of psychedelia (Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!), flawless Wings hits (Band on the Run, Let Me Roll It, that Bond theme), plus tributes (a very moving I’ve Got a Feeling where he ‘sings’ with John on the Apple rooftop; a gorgeous Something for George; god knows both would have hated such mawkishness), an overload of naff that nevertheless made me smile (Wonderful Christmastime with choir and falling ‘snow’; the music-hall-Paul of the unexpectedly beloved Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da) and proper tearjerkers (Let It Be and Blackbird obviously, but Love Me Do’s innocence and simplicity got me). This would all have been fine, enough, more than enough. Even when the old crow Ronnie Wood came on to add some sharp playing to Get Back (he’s keen to go back on tour, clearly, Mick, get on the phone would you?), that would have been enough, too. It was already a special night.

But then, in the encore… he introduced Ringo. What?! I’m still punch-drunk thinking about it. This was a whoosh across the universe.

Ringo Starr is 84, the oldest Beatle. On he ambled, a slight figure, and then a kit was slid on to the space behind him. The noise in that room… “Get behind your kit, la,” said Paul. They did the delightful reprise of Sgt. Pepper then Helter Skelter, a loud, powerful, heavy blast. And then he was off, peace signs flashing as ever, so we just looked at each other, dumbfounded, because there was nothing left to say. Then, with barely a second to breathe and take any of this in, McCartney delivered perhaps his finest moment, the triple punch of Abbey Road’s glorious finale – Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight/The End – which finished off the night. I’m out of words. Love you, Paul. See you next time.

Setlist

A Hard Day's Night

Junior's Farm

Letting Go

Drive My Car

Got to Get You Into My Life

Come On to Me

Let Me Roll It

Getting Better

Let 'Em In

My Valentine

Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five

Maybe I'm Amazed

I've Just Seen a Face

In Spite of All the Danger

Love Me Do

Dance Tonight

Blackbird

Here Today

Now and Then

Lady Madonna

Jet

Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!

Something

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da

Band on the Run

Wonderful Christmastime

Get Back

Let It Be

Live and Let Die

Hey Jude

Encore:

I've Got a Feeling

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

Helter Skelter

Golden Slumbers

Carry That Weight

The End

Madonna, O2, London, October 15, 2023

Image: Getty

“Only when I’m dancing can I feel this free”

“I think when you start off in your life with a very big slap in the face you have a different view of the world. You just do… There’s a line in my [Madame X] script, when my mother dies, I get back up and I keep going. And [when] all my friends died of Aids, I get back up and I keep going. Basquiat dies, and I get back up and I keep going. This stranger rapes me with a knife to my throat, I get back up and I keep going. My ex-husband betrays me, I get back up and I keep going. My brother betrays me, I get back up and I keep going. Either you have that mentality that you get back up and keep going, or you sit around, thinking about what people are thinking about you all the time. The challenges I’ve had, since I was a child, are the things that make me realise how precious life is, and leaning over and kissing my mother’s lips in a coffin made me think… in the blink of an eye, everything could change. I’m not wasting one second of it, and fuck anybody who tries to get in my way.”

– Madonna, interviewed by playwright Jeremy O. Harris, 2021, V magazine

It feels like there are artists who have always been around, present in your life, in your DNA, in culture, and you can’t remember a time before them. Some are no longer here (Beatles, Bowie), some are here but are well into their twilight (Dylan, Elton, Stones, McCartney), but the list of pop stars who are still interesting, still making songs worth hearing, still pissing everyone off, still completely themselves, still breathing… it’s a short one.

Madonna has outlived, outwitted and outlasted every motherfucker who ever went up against her. Obviously, Beyoncé has come the closest to a dethroning. Sure, people adore Taylor Swift. I find her a nice girl, and some of her songs are good, though she is undeniably rather dull. Gaga has done a few good songs and she’s trying her best (like Madonna, she is a Bowie obsessive). But the copyist is the copyist, even if Gaga is a better actress. Adele’s great as both songwriter and singer but her ‘local girl done good’ shtick is as fake as her nails. George Michael had prime years where he was on her level but could never last or listen. Prince (born two months before Madonna) and Michael Jackson (born 13 days after), both of whom she adores, shone brightly and burnt out, like many others.

Nobody else comes to mind. No other man or woman has come close, kept up or worked harder. For 40 of my 46 years on earth, there has been one dominant pop star who remains standing. No artist has done a better run of singles, none. Sixty-five-year-old Madonna lives exactly how she wants and it’s tough shit if you don’t like it.

I had never seen her live, for two reasons. Firstly, the best tickets have always been eyewateringly expensive and I couldn’t justify it. Secondly, she doesn’t play many of her hits. While I admire that on an artistic level, I didn’t want to pay £300 to listen to half of a new album, no offence. Then she announced the Celebration Tour, which began its 78 shows in 15 countries with four nights at the O2, starting on October 14, the night before I went. It was different: her first not in support of a new album, with a decent price range and big songs promised. I failed to get a ticket. The cheapest ones – a still not-cheap £90-£150 – went, fast. I hadn’t given up hope of going but it felt unlikely. Then last week I was at one of my offices (Time Out, as it happens) and someone said a few tickets had dropped back on. I immediately saw a bad seat (Block 406, at the vertigo-inducing top of the arena) on sale for £135. Sold! I was thrilled and walked around smiling for the rest of the week.

On Sunday, a stressful travel situation had me arriving after 8pm. I bumped into a journalist I know in the lobby and said, half-joking, maybe I’ll ask if they’ll move me out of the nosebleed seats? I’ve seen plenty of gigs up there, I’ve done my time in the 400s, I convinced myself. Nothing to lose. I went to customer services and said, extremely politely, genially, “Can I be honest with you? I’ve got a shit seat. It’s so steep and the narrow stairs are anxiety-causing, would you by any chance be able to move me? I know it’s a long shot but I’d be extremely grateful for anything you can do.” The young guy behind the desk took this in and said, “let me look, it might be possible”. There are always spares dotted around for any ‘sold out’ gig at a place this size. Swiftly, he returned with a Block 111 ticket. My mouth fell open. I’d had a bad week and decided I deserved it. I thanked him profusely, realised it was bashert (Yiddish for ‘destiny’) and virtually skipped away to my amazing new seat.

Time-travelling for a second, it was 1986 when I found her. My mum, not honestly a huge fan of music made after about 1980, bought True Blue on vinyl. I had never heard anything like it. And the cover! This perfect, androgynous, spiky-haired girl, head back, eyes closed, in ecstasy. It makes me laugh to think mum was only 35 at the time! I saw the video for Open Your Heart soon after on Top of the Pops; in a vibrant Cabaret-inspired performance she plays a dancer at a peep show being ogled by multiple men (talk about the male gaze, this was only 11 years after Laura Mulvey coined the term) and one short-haired woman. She was 28, I was nine (and soon to see Labyrinth at the cinema, a life-changing event). You can track your life by her songs, everyone who loves pop music can.

So many beats of her career are my music memories. 1989: the cross-burning/Black Jesus Like a Prayer video? The furore was so significant, it made the news; Express Yourself, that choreography, that gorgeous suit; Vogue, a video for the ages; 1990: the best greatest hits album of all time, The Immaculate Collection; staying up late to watch Justify My Love premiere on Channel 4 after its MTV ban; I rewatched it yesterday and it is still a stunning piece of erotic art; 1991: I was a scandalised 14-year-old when In Bed with Madonna, still a masterpiece, came out; 1992: SEX, a book of her fantasies, still subversive and controversial 31 years later, was published. I’ve never seen a physical copy, but its extremely explicit contents, much of which are BDSM-themed, still have power to shock the easily shocked (the only thing that makes you cringe is the presence of Vanilla Ice). The pop video as a piece of cultural record and remembrance is nearly dead, but I have images from her 90s videos, like Erotica, Human Nature, Secret, Frozen and Ray of Light, burned into my brain.

Ghosts roam the stage as she takes you on a journey, starting with her 1978 arrival in New York from the suburbs of Detroit with $35 in her pocket, a much-repeated but true story. She has no money, nowhere to live, no job and no way to survive. We get a tour of NYC’s filthiest nightlife, where she is (fictitiously) refused entry with Jean-Michel Basquiat, her then-boyfriend, to queer club Paradise Garage. We see big-screen clips of CBGBs and Danceteria, as she performs her first two singles, Everybody and Burning Up. A run-through of a young life in a city where she posed nude for cash, lived in a rehearsal studio without a bathroom and dated men so she could wash (“yes, blow jobs for showers!” she said, matter-of-factly, on opening night). It was NYC where she was assaulted at knifepoint aged 19. It was where her friends were soon to become ill. This New York was not like it is now, corporate and unaffordable. It was dirty and dangerous. Her 1980s life was about survival, then, and is about survivor’s guilt, now.

Not everything completely works. Some of the songs have different backing tracks to the originals, which works sometimes (fantastic remix of Ray of Light) and not in others. This despite her English musical director Stuart Price, who has done a magnificent job with the music, saying, “what we realised is that the original recordings are our stars”. Would a live band have been better? I don’t think it would have made any difference to my enjoyment. I’ve also heard some claim the vocals are on tape: not true. Her voice sounds brilliant. The narrative falters in the next section, with its vague stab at the usual let’s-wind-up-the-Catholic-Church stuff (big crosses, a little tired), before the revived Blond Ambition Tour velvet bed has M getting into a bit of groping with a female dancer in the Gaultier conical bra with a rubber hood on (quite fun). There was also a slightly strange tribute to Prince, with his unreleased solo placed back into Like a Prayer; a dancer mimes to it on his ‘symbol’ guitar, while wearing the My Name Is Prince cap with chainmail. (Later, a parade of other heroes appears on screen: Nina Simone, Angela Davis, Brando, Bowie. Then Sinead, which I’m taking as penance for how uncharitable Madonna was at the time of the SNL incident.) It’s unfocused compared to the brilliant first half, though it does all get back on track with the deathless semi-Abba hit Hung Up, which she performs flawlessly, at first blindfolded, with topless dancers gliding around her, an homage to her movement heroine Martha Graham, before stopping for a quick snog with a female dancer. The usual.

The sharp, hugely fun Bob the Drag Queen reappears up to tell us exactly who we’re watching before Vogue, which turns into a fantastic Paris Is Burning ball, with each dancer walking while M holds a ‘10’ sign, sitting alongside none other than FKA twigs, as good a dance judge as anyone (this was Madonna’s oldest, 27-year-old Lola, on the first night). Bob reads the ball using the lyrics of Beyoncé’s Break My Soul, nice touch. Her twins, Estere and Stella, only 11, DJ and walk, respectively. Another of her children, Mercy James, 17, plays piano, exquisitely, on Bad Girl. Before a brilliant La Isla Bonita, her son David Banda, 18, plays acoustic guitar on deep cut Mother and Father, as she honours his mother, who also died of Aids (only the presumably non-musical Rocco, 23, is missing). All the figures of her life, those lost forever and remembered, those who keep her going, are present in some form. This night is about what she has lost – her mother when she was five, her friends and mentors and heroes – and the family gained: the one you choose, the one that chooses you. Beauty’s where you find it.

After that high point, there’s some filler – Bad Girl, Die Another Day, Don’t Cry for Me Argentina, Bedtime Story – that would be better replaced by missing hits. There are also understandable musical interludes without her on stage, there to allow costume changes and the taking of some breaths backstage, and they are not very interesting. But that’s just because you crave her being there. It’s almost intolerable when she’s offstage because you know each second gone is one closer to the end of the show.

Because of that broken curfew – she’s always late – the encore was absent, but honestly I don’t think I missed much: it starts with a taped version of Like a Virgin, accompanied for no real reason by a tribute to her relationship with Michael Jackson and a mashup of her hits into his. Of course, he would have performed This Is It here and died trying to do so. They’re on the main screen together in some sort of AI silhouette dance, which looks cheap. And let’s take an eyebrow-raising moment to ponder the wisdom of it. Is Like a Virgin (!) the best song to use for an MJ tribute, girl? Awkward. The show ends with a couple of later cuts, 2015’s great Bitch I’m Madonna and 2009’s Celebration, which includes a dash of Music, as dancers appear as incarnations of Madonna in her most famous costumes. Not the most banging encore, you have to say. Maybe I can quibble about the songs not played but what’s the point? I wish I had spent the last 30 years of my life seeing her live, frankly.

You can’t be cynical in the presence of the greatest pop star who has ever lived, an Italian-American Catholic who has been excommunicated three times by the Vatican, who only four months ago spent five days lying unconscious in the ICU. Her life is a triumph of spirit and work over obstacles and she is ready to stop treating her hits as a chore. You want pop stars to be like this: eccentric, unrelatable, thrilling, stubborn – never ordinary company, only extraordinary. Is it preferable to think you could have a pint with your fave, like a Bruce or a Liam? That’s not what I want.

I’m forever removing the word ‘icon’ when I’m at work, because it is ubiquitous in copy. You can use it literally, to talk about religious works of art. But you aren’t permitted to use it to describe every pop star/actor/public figure who does something well. On vanishingly rare occasions, when hyperbole takes your mood, it can be used to describe actors (she’s told you who: Garbo and Monroe, Dietrich, Brando, Jimmy Dean, Grace Kelly, Harlow (Jean), Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Rita Hayworth, Lauren [Bacall], Katherine [Hepburn], Lana [Turner], too, Bette Davis… ladies with an attitude, fellas who were in the mood) or musicians (Bowie, M’s muse, Elvis, MJ, Aretha, Prince).

I’m going to say it, though, because she is a religious work of art: Madonna is an icon. To be in a room with her even for a short time is to experience the 20th and now the 21st century of popular culture. She makes you feel as powerful as she is. In a remarkable speech in 2016 at a Billboard event where she was honoured as Woman of the Year, she said the “most controversial thing I’ve ever done is to stick around”. In the same speech, she said “to age is to sin” and there is no doubt that Madonna is powered by the misogyny and bullying she faces (and much of it comes from women). Every person who calls her an old bitch, who says don’t wear that short skirt or those fishnets, who says take off that make-up or stop putting that filler in, or filter on, your face, cover your tits up and stop showing your 65-year-old ass to the world… all are reduced to rubble. She discards every person who has tried to harm or shame her, from clerics to critics to cops. She burns them all on a fire until they are ash, then smokes their remains. I saw a few fans online whining about her being late or not getting 100 per cent of her hits.

To them I say: be quiet. You’re lucky to be alive at the same time as Madonna. This isn’t your show, it’s hers, and the ticket price grants you an audience. You get two hours of near-perfection. Show up, do as you’re told and kneel.

Image: Getty

. ‘It’s Not a Party... It’s a Celebration!’ (opening by Bob the Drag Queen)

. Nothing Really Matters

. Everybody

. Into the Groove

. Burning Up

. Open Your Heart

. Holiday (with Chic’s I Want Your Love)

. Live to Tell

. Like a Prayer

. Erotica

. Justify My Love/Fever

. Hung Up

. Bad Girl

. Vogue

. Human Nature

. Die Another Day

. Don’t Tell Me

. Mother and Father

. I Will Survive (cover)

. La Isla Bonita

. Don't Cry for Me Argentina

. Bedtime Story

. Ray of Light

. Rain

Abba Voyage, London

This review contains spoilers

“To be, or not to be? That is no longer the question,” said Benny Andersson from Abba, last week, at one of the weirdest and most astonishing nights I’ve ever had watching a concert. God, it’s hard to know where to start. Well, it started with a long, dark walk through one of the most grim areas of London. Stratford has been regenerated, incoherently, over the last couple of decades, with much of the new-build ugliness coming in the post-Olympics ‘legacy’ period of the last ten years with billions more in investment on the way. As it stands, what is there has no architectural consistency, style or substance. This part of E15 seems to contain only unsightly boxes in which to live. There is little sign of people, shops, restaurants, bars, cafés, community centres: life. If an alien landed there, they’d think, “Blimey, isn’t London shit?” And perhaps part of the joy which followed that long, dark walk around the unlit bypasses (where I accidentally walked into a protruding metal bar, giving me a magnificently large and painful bruise on my arm) and bleak, community-free streets lived in contrast to this lifelessness because of it, not despite it. If the venue was in the middle of Leicester Square or a buzzing neighbourhood, it’d have already taken the edge off the technicolour shock that hits when you reach the 3,000-capacity, sustainably designed venue, as collapsible as an Ikea flatpack cupboard: boom, you are in a hen night. People are simply… happy. It feels like quite a few are not here for the first time. Some are in Abba cosplay, from glittered catsuits and feather boas to electric blue satin flares. The crowd spans generations. There are daughters with their mums; there are entire families out on a birthday trip; there are gay couples in matching outfits. It is adorable, a delight even before you go into the arena.

Abba, like many other artists who were successful in the 1960s or 1970s, endured a disrespected decade, in the UK at least, in the 1980s. From Dylan (the maligned Christian period; badly produced, average albums) and Bowie (Tin Machine; critical hatred which lasted until Glasto in 2000) to Neil Young (sued for not sounding enough like himself), McCartney (Frog Chorus; derision for his wife; the thumbs-up cringe, started by Smash Hits) and more, their legacies were not burnished by being in their thirties or forties; they were sneered at and called ‘old’. Boomers’ reps began their restoration in the 90s and the same happened to Abba, who were already into their mid-late twenties and on their second marriages when 1974’s Eurovision breakthrough came. A fan’s Google review of their 2021 album, Voyage, their first in 40 years, has as its first line: “I have been an Abba fan since way back when it was so uncool to love them.” Björn Ulvaeus (the one who plays guitar; Benny is on keyboards) spoke to that, too, in a Guardian interview last year: “In the beginning of the 80s, when we stopped recording, it felt as though Abba was completely done, and there would be no more talk about it. It was actually dead. It was so uncool to like Abba.”

The newfound appreciation back then usually came from a younger band who grew up with your music talking you up in interviews or covering your songs (in Bowie’s case, Nirvana and NIN did the trick). In Abba’s case, the beginning of their reappraisal was brought forth by the great British duo Erasure, who made similarly perfect pop music. Their four-track Abba-esque EP, released in June 1992, was a sensation in the UK, giving them their only number 1 record. It was the sound of that summer, a wonderfully queer package filled with glitter that was dropped right into your living room via Top of the Pops for weeks on end. Five months later, Abba Gold transformed the band back into what they always were: beloved creators of some of the best pop songs ever recorded. Erasure’s covers and that album, which has sold 30 million copies and is on a par with Queen’s Greatest Hits as the best singles collection ever released, hit people my age like the freshest songs we’d ever heard. Even my parents, no more the right age to be into Abba than I am, being the same age as the youngest member, Agnetha Fältskog, bought it.

Two years later, I fell in love with a wonderful Australian film, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, which had Abba as a guiding light for the characters and was the second time I’d seen drag versions of Frida and Agnetha (the first being Erasure). The performance, by Guy Pearce and Hugo Weaving, of Mamma Mia, in the film’s finale, knocked me off my feet like a lightning bolt. I didn’t see Toni Collette and Rachel Griffiths doing the same in Muriel’s Wedding until years later, but I know it had a similar effect at the time (the band have always had vast popularity in Australia). The final piece of the puzzle, Mamma Mia!, arrived in 1999 and has become one of the most successful musicals of all time. The two film versions of the story – a girl searches for her dad on a Greek island, set to their music – have between them made a billion dollars at the box office. There are also two other Abba-related events on in London right now – the long-running West End musical, of course, but also a restaurant, themed around the films, at The O2. While I have no interest in buying a ticket to either, I take great pleasure in how their music has become a soundtrack to pure joy, played endlessly at parties and weddings, fuelling warm nights out among friends. There is a Swedish concept, lagom, which has no direct translation, but roughly means “everything in moderation”. Abba are wonderfully, vibrantly… anti-lagom. To attempt a technological transformation of their music and person, who else could do it first?

Abba Voyage began with the chilly, electronic brilliance of the title track from 1981’s The Visitors, a gutsy choice, given that it was the last album released before they split. And then… there they were. Sort of. Yes but no. My eyes blinked, my mouth dropped open. My ears were fine with the music of course, which sounds as punchy live as you’d hope: a ten-piece band, including three backing singers, work behind vocal stems from their live shows and original recordings (the band was put together by Klaxons’ keyboardist James Righton). But what the actual fuck is going on here? Seriously. Your eyes can see these four figures near the back of the stage… and they look real. Staggeringly, confusingly real. That is, they look like mid-70s Abba, still young. The adjusting to the concept comes when you see them on the 65-million-pixel LED screens, which are raised and dropped as required, and wrap around half the arena in a half-moon shape, looking uncanny valley, video-game waxy. Okay, I get it. I adjusted my senses. And then it didn’t matter, I fell into the video game, becoming immersed in the whole thing. It felt like forgetting the difference between 2D and 3D. Later on, some of the band and the three singers came out of their position stage-right to the front (where of course Abba cannot move to). I turned to Leah and said, only half-joking, “How do I know they’re real?” This was a leap into retro-futurism that, even though I had been told plenty about the show by multiple people, I wasn’t ready for.

Few bands have crafted pop songs as good as this. SOS, Knowing Me, Knowing You (reclaimed from its cheesy Partridge home), Does Your Mother Know, Lay All Your Love on Me, Gimme! Gimme! Gimme!, Voulez-vous… they kept coming. And the show could afford to leave bangers out, too. There was no Super Trouper, Take a Chance On Me, Money Money Money, The Name of the Game. It very much had a gig feel, rather than that of a theatre performance, a museum piece or a screening. Each member makes between-song speeches, which only hammers home the weirdness of this whole enterprise: it’s young faces talking with old voices, because the sentiments are coming from the band as they are now, aged between 72 and 77. Before Fernando, Anni-Frid (Frida) Lyngstad talks about her grandmother. This makes me well up and I start thinking about my friend Ann-Charlotte, who is extremely dear to me. She is also a Swedish woman, born in Stockholm, and is around the same age as the band, with a sister called Neta (Agnetha). I thought of her, sitting at home in Gothenburg in her flat, of how much I miss her, of the Bowie shows we saw together. For decades, she worked as a ship’s bursar on cruises: a real sailor. We have talked often of her parents and grandparents, of Sweden in the twentieth century. We talk about food and family. I’m lucky to be her friend.

After this relentless bombardment of pop perfection and incredible visuals, about half way through there was a smart moment that was very gig-like in its pacing. The band vanished as the screens fell for a couple of songs, set to a Studio Ghibli-style animation that had me gripped (and no doubt sent others to the bar). Near the end, another moment took me wonderfully out of the augmented reality computer game. The intro to Waterloo was a funny speech about how the UK gave their Eurovision-winning song nul points (how embarrassing), but was then surprisingly followed by the faded, low-resolution, ESC performance on the screens. In an instant, you saw how imperfect humans are. A bump on the nose here, a hair out of place there. The Abbatars (lol) are not like that, they are blemish-free, glassy beings, made better-looking than their subjects were, with more perfect teeth and skin and hair and bodies. This is how we all wish we looked, or how we thought we looked in our twenties. But we were not that flawless, we were just as real as that Waterloo clip. Abba Voyage, being watched in the present day with our young lives in the past, replaced by that adulthood-bill-paying-body-aching-losing-a-parent-reality, makes you feel that you can remain young forever. Everyone there felt it, even if you weren’t old or young enough to be an Abba fan first time around, as I wasn’t. It’s not even really about the band. It’s about you, about applying what you’re seeing to yourself. It became about what you’ve lost, how innocent you were back then, your self-vision being yours to remake and be wistful, and perhaps a little inaccurate, about. The real imperfections of your human face and body, ironed away just for one night.

The last song is the heartbreak of all heartbreaks, The Winner Takes it All, the pinnacle of the band’s emotional core. That song is a lot. Björn wrote it about his divorce from Agnetha and she sings it. What it must have taken to do that, can you imagine? “Building me a home / Thinking I’d be strong there / But I was a fool / Playing by the rules… Somewhere deep inside / You must know I miss you / But what can I say? / Rules must be obeyed”. That song is too much. Too many people think Abba are superficial, the embodiment of music that electric blue satin flares and silver-glittered platform heels are worn to, but these are serious musicians. There is magic in the marriage of Benny and Björn’s songwriting and out-of-this-world production, and their ex-wives’ incredible, dovetailing voices. In the post-split years, another thing that happened was the withdrawal from the public eye of Agnetha and Frida, leaving the men to sell everything from their majestic score to Chess to Mamma Mia!. The stage has been half-empty for a long time. Abba Voyage returns half of that credit where it belongs, to the women who sell those deathless songs. We now recognise how often women are denied their due in music, so it is a particular joy that the show makes clear the stars are Frida and Agnetha; it’s about their reclamation of self, their reclamation of the stage, their stunning chemistry, their return to the public’s mind after four decades of their ex-husbands doing all that talking and leading (to this day: they did not wish to do any promo duties for the album last year).

At the end of the show, as the wooden venue still bounces with the party, the young Abba take their bow. And then… the band as they look now appear and basically everyone lost it. A wave of irresistibly manipulative emotion swept across me. On press night, a third version came out on stage, the actual real-life flesh-and-blood Abba. That would definitely be too much! But this appearance of the virtual four in their seventies brings home that Abba Voyage is about the passing of time and the beauty and immortality of music. This show could play in a thousand years just the same. The difference now, and it is crucial, is that it has been created while the members are still alive. It is not ghoulish to watch, like those appalling hologram gigs, which Abba Voyage is miles away from because this tech is universes ahead. But it’s not about tech. They are in control of their legacy and that is their privilege. It simply could not have worked without the artists being available to put on motion-capture suits, surrounded by 160 cameras, perform the show in entirety and use that as the base to create this spectacle on top of.

The estates of dead rock stars are checking their bank accounts as we speak, trying to figure out if they can do this. Not everyone has Abba’s eye for detail or creative control, or their deep pockets, as the show has to make £140 million to break even, and it will make a lot more than that in the end. Certainly, the rich estates of dead artists – MJ or Elvis or Freddie Mercury – would happily hire an impersonator of approximately the right size, choreographed to get the moves right. But that does not solve the problem of the face. A face-cast mask, think Bowie’s in Cracked Actor, won’t do it. An impersonator can’t do it. You cannot de-age a face if you have no access to… well, not to be morbid, but… their skull. Can’t do it. “Capturing every mannerism, every emotion, that becomes the great magic of this endeavour. It is not a version of, or a copy of, or four people pretending to be Abba. It is actually them,” said Ludvig Andersson, one of the show’s three main producers (the others being Svana Gisla and music video director Baillie Walsh, with the tech wizards at George Lucas’s ILM doing the thousands of hours of work to bring it all together). The creative director of the project, incidentally, is none other than fellow Swede Johan Renck, who directed the videos for Blackstar and Lazarus. But if it’ll be difficult for late singers to go on their own voyage, there is no doubt that living artists like the Stones or Elton or McCartney, who definitely can afford it, will be hiring those suits any day now. I thought about Bowie, because his estate has money and no soul, and I bet they’ll find a way to have a go. It’d be Ziggy, because people are basic, but I did allow myself a moment to imagine going again to my show, 2003-04’s Reality Tour. What would it feel like? Like time-travelling, I suppose, something acknowledged by Benny at the start when he made reference to the show being like having their own Tardis. You wonder if one day there’ll be tech that lets the projection, or whatever it is, move around more. That would be wild.

Surreal is an overused word. But I couldn’t get over the details. You can see their pores, the swishing of their lavish costumes (made by Dolce and Gabbana, among others, in a more tailored and modern imitation of their 70s style), the hair on Benny’s chest. It’s all perfect by design. Abba Voyage is the coolest thing, by some distance, a pop group has ever done. The band will never get tired, or any older, or split up (again). It’s a bizarre combo of something that is glassily perfect, but somehow has mountains of soul and chemistry, being smashed together with timeless music. And they’ve managed to do all this without ads, corporate sponsors and branding, which is hugely refreshing. The show can travel on its own, sustainably, with its only partner, a shipping company called Oceanbird. But I hope it stays in London for as long as possible, because seeing it again is in my future.

The naïve part of me hopes Abba Voyage does not lead to a Black Mirror-ish dystopia and become the sole future of live music, for heritage acts or otherwise, that its tech is used carefully, with integrity, but we know this won’t happen. It doesn’t matter. Abba did it first and I can’t see anyone else doing it better. This exciting, ridiculous, innovative, psychedelic show will never be equalled. It took my breath away.

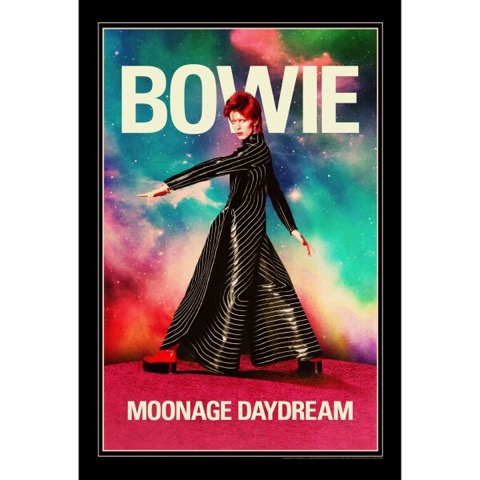

Moonage Daydream

In early September, I saw Moonage Daydream at its premiere at the BFI Imax in Waterloo (followed by an amazing after-party at the Blavatnik Building, part of Tate Modern, where we danced to Bowie with Eddie Izzard: life level unlocked). Hearing too much about a film can be trouble. Trailers and reviews give you inklings while you try to avoid spoilers. But this film, which has been called an immersive (boy, is that an overused word) documentary, I’d already seen most of, so it felt organically like I had to prepare my thoughts and expectations in advance. I’d decided that the absence of much new footage, which friends rather than reviewers told me about, wasn’t going to bother me, but that turned out to be easier thought than done and not even the biggest problem with the film, ironically.

Its creator, Brett Morgen, had been courting hardcore fans for months. The early discussion last year about the film in the press continually said that it was based on ‘thousands of hours of unseen footage’. You might, then, expect quite a bit of it to be in there. Before Moonage even had a release date, much of the narrative said stuff like: ‘While exact details about the new Bowie film are scarce, unseen concert footage is supposedly a central element to the documentary’.

Perhaps this mixes up the difference between ‘unseen’ and ‘rare’ (pretty basic for a director to know the difference you might think) because at no point was this big fat selling point disavowed by anyone to do with the film. Wait for it, surprise coming up, it turned out to be a complete lie and there is very little new stuff; I’d estimate about 5 per cent. The film’s major find is some footage from the Isolar II Tour, shot at Earl’s Court in 1978. We get all of “Heroes” (though the first half is audio only, as we’re stuck with seeing fans coming in, for some reason) and a bit of Warszawa. There’s a little bit of Diamond Dogs Tour footage, too. But that is it. In a recent interview with the Guardian Morgen said ‘if you’re a hardcore aficionado, there’s enough new material to satiate you’. *turns to camera* *eye-roll*

He also said Ricochet was his ‘holy grail’ when giving a story to Indiewire of finding it like he was Indiana Jones. It’s one of the extras on the Serious Moonlight DVD and is not hard to find. It’s not a big treasure. It’s some ‘stranger in a strange land’ footage of Bowie going around looking vaguely like a colonial ruler, bowing his head to foreigners. As always with him, it is well-meaning but it shouldn’t have been excavated here as the heart of the film. It’s nowhere near that interesting. But Morgen loves Ricochet so much he repeats the same footage of Bowie going up and down an escalator three times to hammer home his point (it’s not the only reused, repetitive footage). One assumes the point was Bowie at his best making music when he was searching for something. Then when he found it (the wife) he became so contented that his music went bad. Good grief.

Morgen had discovered all this material after spending five years sifting through the vast Bowie archive (made up of some 5 million ‘assets’). He was only the second party allowed in there, after the V&A curators. Francis Whately did the BBC’s great Five Years docs, but going by this interview I don’t think he had access officially, though the estate were helpful (and Bowie was alive when he started, so it was different). I don’t doubt Morgen’s love for the music and his intention – to show the world why we’re all so devoted to Bowie – is pure. He obviously loves David very much.

But despite what he says, Moonage is not for fans; it’s for everyone else. It’s a Bowie gateway for people who are coming to him relatively fresh and, at a basic level, it does fulfil its aim. What is better than seeing a massive amount of Bowie footage on a gigantic screen? That’s always a good time. There were things I liked about it, such as the voiceover narration, which uses Bowie interviews spanning decades; that worked very well. Particularly insightful were clips from the superb Mavis Nicholson interview), recorded in 1979. It set the context well of where his life was at age 32. If he came off a bit cold or distant emotionally in those 70s interviews, that’s because he was. And therein lies the problem. So much of the film’s narration is based on early interviews, when he was just as stupid as any of us are at 26. Morgen tries to balance the interviews out by using more recent ones, when Bowie’s older, wiser, more aware of his place, and has a deepened understanding of his creativity and process. But it’s not enough. And worse, all the interviews were utterly humourless. What? David Bowie was a funny man, with a super-dry sense of humour. Using all these interviews to make him sound incredibly pretentious achieved what? Sometimes he was pretentious, nothing wrong with that. But you’re cutting off half a personality by making your film so po-faced, by believing the audience doesn’t deserve even one laugh as it’d break the mood?

Having said that, I am grateful that the film has a short section on his paintings, as it’s overdue for that aspect of his artistry to be taken seriously. Another part on Bowie’s half-brother and his illness, and his mum keeping her own emotional distance, was well-handled. The Russell Harty interview is a hoot, because he is just so incredibly weird compared to what English culture was serving people in 1973. The best-selling single of the year was the jaunty kitsch pop of Tony Orlando and Dawn’s Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree. On TV it was the era of The Benny Hill Show. The most-watched TV broadcasts of the year were Princess Anne’s wedding, then Eurovision. It is impossible to overstate how the nation would have dropped its dinner when they saw this guy who looked like he’d just got off a spaceship from fucking Mars. Harty, who was deeply closeted, sneers and goads him over his bisexuality for the audience’s amusement yet Bowie’s relative innocence and charm survives the assault. Kids who loved him back then were beaten up at school and called homophobic slurs. Being a Bowie fan was dangerous and these clips are important to show you just why. The film doesn’t pretend any of this didn’t happen and handles his sexuality well, which I appreciated.

Moonage’s aim is to give a mainstream audience all the information so they can fall in love with him just like we did. That’s a highly valid idea for a film! But, how dull, nearly all of the material is derived from the 70s and early 80s. There is a bit of him looking hot and inspired while covered in paint on the 1995 set of Hearts Filthy Lesson (which we don’t hear), but it’s in the film three times. There’s some collaged, thunderously loud versions of Hallo Spaceboy live in 1996/7, which I enjoyed. There is a nice juxtaposed Space Oddity of old with the 1997 NYC birthday concert. There are also some great bits of the Louise Lecavalier dance footage shot for 1990’s Sound + Vision Tour (but without any context, because it doesn’t fit the narrative, more of which later). We get about a minute of the ritual footage from the ★ video, without Bowie in it, which doesn’t make sense without context either, then we see about five seconds of him. There’s a little bit of soundless footage from a Reality promo to, I assume, compare young with old (if 56 is old). But that is it for anything after 1987. All this might take up perhaps ten or 15 minutes of the 2 hours and 15 minutes running time. Slim pickings.

It all means that we are subjected to the deeply boring reiteration of the late-work cliché. What I mean by that is the untrue and insulting idea that Bowie’s great music was over after 1983 (if not 1980). The other week in the Sunday Times, Morgen gave an interview in which he said that when Bowie met Iman in 1990 his work ‘plateaued’ [‘reached a state of little or no change after a period of activity or progress’]. How can he think that? The same paper printed a ‘ranked from worst to best album list’ that has ★, elevated because it’s ‘rich in symbolism’ (i.e. they consider it tragic), as the only album in the top ten made after 1980. 1. Outside is placed at 20 out of 26 (the Tin Machine albums are excised but the band is called ‘excruciating’). Look, I can understand why Morgen believes the general public wouldn’t want to watch a film that includes more than a small amount of the later work of the 1990s and the late work of Heathen onwards. The media has been ripping Bowie’s mid-career work (1984-99) to shreds for nearly four decades. Wasn’t this an opportunity to say, ‘Hey, the media has told you his 1990s output was shit, but it’s not!’? Morgen has repeatedly, openly disrespected that work in interviews. Then he backtracks on Twitter and says he loves ‘Heathens’ [sic] and Outside’? Not convincing. There is nothing in the film from Heathen by the way, a significant work that doesn’t fit his Bowie-got-boring-when-he-got-married narrative. And nothing of another important album, The Next Day, which is bonkers. Even back in his beloved 70s, there’s nothing from Young Americans and, from Station to Station, we get a minute of Word on a Wing accompanying a cringe photo gallery of Bowie and Iman, then ten seconds of the title’s track’s train sound! Very bizarre. Why not do a classic final ‘comeback’ section? Tell me a third act where he returns in his sixties and then dies a couple of days after his masterpiece comes out wouldn’t be a perfect ending to the film?

T

Thank god at least that the format isn’t one of those boring talking-heads documentaries. I don’t want to watch people who interviewed him a couple of times, or never met him at all, or ‘famous fans’ making their money out of speaking his name. I’m bored of that, aren’t you? In the last decade of his career he let others speak in his place and it worked, it was smart. But now he is gone. So those who chase that ambulance… I don’t want to see anyone churn out the same old anecdotes or stale cultural opinions for the hundredth time. I don’t dig it. I want him. I want him to speak and sing and be heard and seen. I want more analysis of his music and fewer people talking about his ‘influence’.

Moonage is about getting a new audience to understand the essence of who he was. It’s about young people going to see it and being blown away because it’s all new to them. Bowie is the music not even of their parents, but their grandparents, now. The music of my grandparents was Mario Lanza and Frank Sinatra. Falling generationally in between crooners and The Beatles was Elvis, a grand hero of Bowie’s. When I was young, in the early 1990s, Elvis was long gone, from 30 years before, full generations ago. Not even my parents were old enough to be his fans. Another 30 years has passed and now Bowie is to teenagers what Elvis was to me. I knew the real, beautiful, non-tragic Elvis because my mum and her best friend showed me all the 50s footage and some of the better movies. I didn’t know what happened to him when I was young. But most people did and made jokes about him. It was unfair, Elvis deserved better than to be remembered as a fat Vegas act who made dozens of bad movies. And so as Baz Lurhmann’s eccentric, flawed and brilliant Elvis biopic starts to leave cinemas, having completely captured how he filled the world with electricity, so arrives this film that should fill new people with the same wonder. It probably will, if you don’t know very much about Bowie. That Elvis film injects you with a thousand volts of power and energy and magic; it makes you see why, as Lennon said, before Elvis there was nothing. It manages to be kind of a bad film and a work of art at the same time. I craved for Moonage to do the same. But Morgen is not Luhrmann, he doesn’t have his talent.

A moment on the crime of using blurry footage. Morgen’s insistence on it being in Imax is a nice idea in its ambition. And some footage – D.A. Pennebaker’s Ziggy; the 1978 clip of “Heroes”, the highlight of the film; a bit of the Jump They Say video (no audio, too 1990s), the b/w S+V footage, the 1. Outside painting – works blown up to that scale. But a lot of it doesn’t. There are significant sections that are impossible to see properly because it’s all so grainy and of poor quality. It is unforgivable to put newly discovered Diamond Dogs Tour footage on screen that is virtually unwatchable. There’s a bit from the Station to Station Tour that is significantly worse than the cheap bootleg I have of it – and worse than was seen in the end credits of the first part of the BBC’s Five Years documentary (which trumpeted its ‘wealth of previously unseen archive’ and delivered on it). I’m embarrassed for Morgen. Even Cracked Actor was a mediocre transfer, so was the Serious Moonight Tour footage, so was Glass Spider. Just put the film on Netflix, it’ll look better. This was discussed after my second viewing with an expert (hi Andrew!) and he told us it was because of the differences between what is shot on film (transfers perfectly) and what is shot on video (transfers terribly, cannot be improved). In that case, why use bad, grainy footage at all? It just makes your film look amateurish. Just be honest and say it’s not good enough to be blown up to cinema size.

The first half hour was quite dull, because Ziggy is not my favourite period, but it felt like simply sticking Pennebaker’s great movie on a big screen. That is okay I guess, I’m happy to see Bowie footage again, big and loud. But song after song? By the time we got to the video of Ashes to Ashes looking worse than any bootleg I’ve seen, I had given up. Use my Best of Bowie DVD, mate, it’s better than whatever source you found. In the mid-80s, yes, I get it, he was unhappy. But to set up the high camp of the Glass Spider Tour as the lowest point? Playing only video from it, no audio, no context, was low. Play his entrance in Labyrinth to, what, sneer at a film that created a massive new generation of Bowie fans? Ignore Tin Machine like it never happened, despite its great importance to him as an artist, because it doesn’t fit your narrative? There can’t have been rights issues over all of it. And putting in the Pepsi ad proved what? It’s a bit of fun. This film is so painfully serious, it shouldn’t have been. It all continues to pour fuel on the idea that Bowie had ‘bad years’ without taking a second to look again and see if there is much of value. He just keeps refusing to expose the audience to anything from after 1983. We hear Spaceboy and a bit of ★. That is it. Not one more second from the last 33 years of his career.

I’m not a fool, I know this is a fan’s review. You can’t assess movies properly that way. It’s too personal. But when the director goes out of his way to appeal to fans, going so far as to make a trip to the Liverpool Bowie convention (I met him there, he was very nice), you’re saying that this is a movie as much for us as anyone else when it’s not. New people, and those who always liked him a bit and wanted to know more, should go on their Bowie journey and Moonage Daydream will help them do it. It’s why the film reviewers, who might like him just fine but aren’t mad fans, all gave it five stars (the music reviewers like it less). It’s why the audiences I saw it with adored it. But setting out that being with Iman made him boring/out of ideas in his artistic life jarred (feels like the estate insisted on her being dropped in). Never mind that he put out his weirdest fucking work, 1. Outside, three years after they got married. The estate are going to manage his legacy however they want following the end of the first five years of what I can only assume were his wishes (when great stuff like Glasto and Visconti’s Lodger remix came out, which he consented to). We have walked through that looking glass now. They’ve sold the songs to Warners for £125 million and now you are going to be told what to think about him. One recent ad campaign was a remix by the DJ Honey Dijon for the home exercise bike company Peloton, about which she said: “I chose Let’s Dance because it’s a celebration of music and movement – just like Peloton!”

I don’t think one person is going to realise Bowie is amazing because they’ve heard a piano-led, slowed-down version of Sound and Vision advertising the refurbishment of your spare room by B&Q (yes, this is a real example). I don’t think one person is going to buy some tat (socks, Barbies, cheap T-shirts, a Low tankard: another real example) and go, wow, I’ve just discovered Baal because of it! I want no part of this.

The film does have a purity of reach, because it takes his artistry and creativity seriously, rather than talking about his clothes or sex life, which is great. I just wish I could see the footage properly and there was some understanding of how he got better as he aged, rather than reinforcing a media-driven cliché of everything going downhill after the 1970s. Worse, setting up that the ‘peak’ we keep going back to is 1972. Are you kidding? His least musically adventurous stuff is the artistic pinnacle because of his impact? This legacy management is out of our hands, but we don’t need to buy into it. I’m disheartened that Moonage is such a disappointment. Not even just that, it’s a fucking mess. Of course, many fans will adore it uncritically because they don’t want to find fault, as this might be seen as a ‘betrayal’ of David. This film will bring about revelations for many and that’s fantastic. But that was not my experience.

I was hoping it’d become one of those documents that we would end up watching, a bit drunkenly, in excitement at its treasures, for years. I couldn’t even say I was looking forward to seeing it a second time. But I did go, because it had to be done. The first 45 mins of Ziggy is still boring. The middle section when we get to Berlin is a little better on second viewing. The incidental music choices are, repeatedly, Ian Fish U.K. Heir and The Mysteries (I guess he did get into my Best of Bowie DVD after all; that’s the menu music). And the last half hour is a dirty, offensive setup, lining up a bunch of great footage – Glass Spider, Labyrinth et al. – to tell the audience that he was shit in the 1980s. All set to a very on-the-nose Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide. We get it, he was great in the 70s, then he committed artistic suicide, then he got married and then he died. What a waste.

...

It’s life, and life only: Bob Dylan at 80

It’s estimated that more than 1,000 books have been written about Bob Dylan. There must be tens of thousands of articles. Millions of words. Even I’ve put down a few. I’ve done reviews of two gigs (Brixton and the Roundhouse) and the play based on his songs, Girl from the North Country, which was published by the only fanzine that Bob himself gets a copy of, Isis. Another time I did a short piece about my dad being at the ‘Judas’ concert. There was even a review of the brilliantly strange I’m Not There, a semi-biopic that I think will hold up well as the years pass.

But writing this, as Dylan’s 80th birthday arrives, is a different matter, because trying to embody the depth of feeling I have for him is… impossible. I don’t know how to do it. How can I possibly use words that have been used before to say things that have been said before about my Bobby? A remarkable, yet ordinary, flesh-and-blood American man whose music will be listened to for thousands more years and inspire tens of thousands more books and millions more words? I can’t. There aren’t enough words in the world or hours in the day to dig out the inside of my heart and shout from the rooftops about what he means to me. If souls exist, and if I have one, I can only tell you that he reaches its edges and turns them inside out. In a very different way to Bowie, as well. He’s all about reaching my brain’s insides, my id, my body, my being; he consumes me, he stands alone. I am made of his music. Maybe Dylan’s meaning to me is more cerebral, less personal. To see what he is, is to acknowledge what he means to the world, whereas to know what Bowie is, is less tangible, but far more a part of my bones. Such different men, but also their stories interweave so much (that’s a whole other article).

As I write this, as we all stumble into the third decade of the twenty-first century, all the old rockers are dropping, the second generation (after the 1950s era’s Elvis, Little Richard et al., of whom Jerry Lee is the last man standing) of popular music stars who, quite clearly, nobody could see getting old at all. It’s a surprise to many that ‘one of the last legendary boomers left standing’ (if I can steal that phrase from a forthcoming book) is reaching 80 at all, I bet, as so many of them died before they were even adults. Even Bowie said, “I had this poetic, romantic, juvenile idea that I’d be dead by 30; that’s what all artists think, I’ll be dead by 30, I’m gonna get TB and die. Aubrey Beardsley and all that.” That he, a drug addict and alcoholic, made it to 69, just about, now feels like some sort of miracle. But it does change your relationship with the music, when its creator has departed. That was the spur for writing this. I decided last week to play his canon, from the second record (1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan) onwards. Almost immediately, I was overcome by emotion that I didn’t expect. Overcome by that young man’s words and his voice, its spoken-word quality, for he has never been a singer in the traditional sense (“I’m just as good a singer as Caruso!”). It took a while to figure out what the sensation was… gratitude. Because the dominant musical figure of my life, David Bowie, is gone. And I don’t remember having a moment like this when Bowie was still alive where I thought: I must appreciate this person because they won’t be here one day and everything will change. Perhaps that’s what this bit of writing is an attempt to do, to show that I am achingly grateful because I’ve realised that I must savour and hang on to every single album, song, gig (one can only hope for more, I’ve only seen him 12 times), lyric and moment while Dylan is here sharing the planet at the same time as me. I am lucky to have lived at the same time as both men. But now Bowie is gone and my relationship to his music has changed, because it was forced to. Thinking about the musical figures I was aware of when I was young, played loudly and often by the parents, it was always Bob and Miles Davis. But Miles died in 1991, when I was 15, so he switched from being an active person, who released music and could be seen in concert, to a gone person. I knew him as a living artist for only a short time. But Dylan? He kept on going. He kept on making albums too and, no, not all of them were great. Some of them weren’t even good, especially from the 80s to the mid-90s (with 1989’s Oh Mercy being a rare highlight). But the point is that he is here. And maybe you shouldn’t care to be heavily critical when that person has given you so much. Having said that, he has had a pretty surprising late-career renaissance, bookended by 1997’s Time Out of Mind and last year’s wonderful Rough and Rowdy Ways, a self-curation of his own legacy and the latest acknowledgment of his mortality. But even if he just phoned it in like Jagger, even if he’d not written a good song since the 70s, I wouldn’t love him any less.

Because love doesn’t work like that. There’s so much in the credit column that even if the debit column builds up a little, it doesn’t matter. It’s complex to talk about the warmth for Dylan that envelopes me and my dad now, especially now my mum is gone. I wish she was here to read this and celebrate the birthday milestone. She’d have a lot to say, for sure, about her Bobby. And what she’s missed eh? Not just five albums – two of his originals and three covers collections – but… he won the Nobel Prize for Literature! That was pretty surreal. When it happened, in fact, it was quite funny to see the fusty old academics and their spluttering, affronted articles talking about a pop singer who’s dared to walk the halls of great poets and novelists. But if the most significant influence on twentieth-century popular music culture doesn’t deserve a Nobel (and an Oscar, he has one of those too) who does? Like all the other gifted Jews who wrote those songs, he’s responsible for a second version of the Great American Songbook. Okay, yes, we can speak up for Sinatra and Elvis as towering figures. And honestly, I think Joni Mitchell is better on each individual count – musician/songwriter/lyricist/producer – than anyone else, full stop. But Dylan is the greatest and most influential musical figure of the last century. I’m not saying anything new here. But does anyone know what Bob Dylan, the constructed persona of Robert Zimmerman, actually thinks about it all? His lecture, given in writing, not in person, to accept the Nobel was sprawling, wild and filled with literary allusions, namechecking The Odyssey and Moby Dick, but it was also very self-aware. I suppose you’d become a monstrous asshole if you believed everything that people wrote about you. He does give the odd interview that lets the light in, just for a second but he’s also smart enough to know his place in history yet be able to brush it off his shoulder. Living long enough to see these types of tributes to your big eight-zero must be like reading your obituary.

It makes me think about how it must have felt for Bowie to witness the mass freakout when Where Are We Now? came out in 2013. It was probably a little like being present at your own funeral. Watching people react as if it were to a joyful eulogy. He had plenty of ego to him, but I suspect he was quite shocked at the outpouring of happiness that greeted his return and I’m glad he got to witness that. I hope Dylan is similarly tickled by how loved he is: perhaps he might catch some of the excellent articles and radio shows that have come out in the last couple of months.

Listening to his early stuff now, you can hear this arrogant, brash young man who knows how brilliant he is. He simply reeled off dozens upon dozens of songs that people will still be listening to for millennia. Sometimes I think about what he’s actually like, because none of us knows him. Only his family get to see past the character of ‘Bob Dylan’. To them he’s just an ordinary zayde (Yiddish for grandfather). A cousin of my dad’s told him that Bob showed up about ten years ago at her synagogue, near Encino, California, which was hosting a social occasion for Chabad (an Orthodox Jewish organisation which he has publicly supported, appearing at a telethon, of all things). A friend who was there told her that this unkempt man shuffled over and started a polite conversation, before asking her out on a date. She had no idea who he was. Equally politely, she said no thank you and he said it was nice to meet her. After he walked away, someone else came up and said, ‘You know who that old man was? Bob Dylan!’

Who else knows him, family aside? Maybe his famous friends (sworn to an omerta for fear of ex-communication). But not biographers or acolytes, and certainly not the bizarre, obsessed fan (one of many) who made a habit of going through the bins outside his house. You might think he’d be understood by others on his level. But even then, a figure such as President Obama found himself beautifully baffled by Dylan – and that was just how both parties wanted it. In 2010, two years before he awarded Bob the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Dylan performed at the White House. There was no rehearsal. He turned up, played one song, shook the president’s hand, tipped his head and gave a small smile, then disappeared. Obama later said, “That’s how you want Bob Dylan, right? You want him to be a little skeptical about the whole enterprise.”

These types of odd stories abound: showing up at his grandson’s school, coming off like the ‘weird guitar guy’. Taking the bus tour of Lennon’s childhood home with everyone else and just sitting quietly on John’s bed. The surely apocryphal tale of mistaking a plumber called Dave for his mate Dave Stewart in Crouch End in the 90s. The author Merrill Markoe, who lives near him in Malibu, has related a decade’s worth of cryptic but magical tales about his Christmas lights; some years they were very plain but later they became a touch more opulent. (I find it strange that any Jew would celebrate Christmas in any way but I know this is a great deal more normal for American Jews than British ones!) Another great story is told by the brilliant writer-director Larry Charles (Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Borat), who walked into HBO with Dylan to pitch a slapstick comedy at Bob’s behest. At the meeting, the head of the network, Chris Albrecht, approaches Bob and says, “It’s so nice to meet you, I have the original tickets from Woodstock!” Staring him up and down, Dylan says, flatly, “I didn’t play at Woodstock” then walks over to the windows overlooking the city and spends the entire time staring out of them. It’s also worth mentioning that Charles resembles a more far-gone version of The Dude – with long hair and long white beard – and at that time was going through a phase of wearing pyjamas every time he left the house, while Dylan was wearing a cowboy outfit like Lee Marvin’s in Cat Ballou. They sold the show but, on the way out of the building, probably because the HBO chairman thought he played at Woodstock, Bob said he’d changed his mind and didn’t want to make a Buster-Keaton-esque comedy sitcom starring himself after all. He and Charles later did make a movie together, the extremely loose and weird Masked and Anonymous.

Then there was the time when he got escorted by the police back to his hotel because a local homeowner in a New Jersey neighbourhood he was walking around in, late at night, thought he might be casing the joint. The deathless standfirst is one of the finest I’ve ever read, not least because, although he lived in the town at the time, there’s no reason to, again, mention the 1969 music festival: Forty years after Woodstock, Bob Dylan is mistaken for a homeless man. There are dozens more of these tall tales.

My dad told me the story that, I think, sums him up best. It’s my favourite because it makes me laugh every single time I hear it. Sometime in the 80s or 90s, an anecdote made the rounds about a guy getting into a lift at a hotel and, to his surprise, there was Dylan. He recognised him immediately and moved toward him, saying, ‘I know who you are, but you don’t know who I am’. To which Bob turned toward him, giving a death stare, and replied, ‘Let’s keep it that way.’

He’s always got his eye on the future. Selling his songs may have, to some, seemed a cynical venture but not only does it secure his legacy forever, it also ensures income for his descendants for the next ten generations. In fact, he’s well known for saying yes to any song licensing request whenever asked and has shilled for products for years, from lingerie to cars to his own whisky. I guess what we can infer from all those moves is that he doesn’t value his music as much as others do, which frankly comes off like a fairly healthy attitude to have. People have spent 60 years trying to understand Bob Dylan. And good for them. But I’m not interested in reading books about his private life or raking over the same old coals in nostalgia rock magazines or buying remasters on the anniversaries of album releases. And I don’t imagine that’ll change when he’s not here. I just want the music that he’s in control of putting out and I can leave the rest.

There’s a Yiddish phrase, I suppose the Jewish equivalent of ‘knock on wood’, which is keina hora. It, roughly, translates to ‘no evil eye’. Saying it out loud makes a fervent wish that a person will continue to have good health. Bob Dylan has reached 80 years old, keina hora. May he have another lifetime to go.

...

Stardust – 2 stars

Prologue

Between lockdowns, on a rare day in the office, I watched the trailer for the Bowie biopic, Stardust, drop on Twitter. Reaction was… uh… mixed. And that was just the trailer. A few reviews already existed, as it had been shown at American film festivals in the spring, so I read them: all the young dudes carried the news, and the news was not good. I knew then that I didn’t want to see it: I wanted to review it. In a display of entirely unearned confidence, I jumped up from my desk and followed the floor sticker arrows around to the desk of Phil de Semlyen, my colleague, the Global Head of Film at Time Out. I said, “Lovely Phil, how do you fancy letting me review the Bowie movie? Okay, I’ve never reviewed a film ever for any publication but I can do it, I think. And someone who knows the subject should do it anyway, so go on, let me! How hard can it be?” He said, “Sure, no problem. If I can do it anyone can!” Such a nice man.

Well, then. Slight panic. I did some research, made notes about technical things, then watched it on the Raindance website. Surely, surely, it was going to be better than early reviews said? Or, best-case scenario, those reviewers weren’t Bowie people and didn’t get it, and it would be filled with Easter eggs for the nerds. Why not? I’m an optimist by nature. Then I pressed play.

It became clear quite quickly that Stardust was, in fact, going to be even worse than the reviewers said. After about 15 minutes, hysteria set in; I couldn’t stop laughing at how bad the dialogue was. Then another 15 minutes passed, the laughing ceased and I started to get annoyed, because it wasn’t even bad in a good way. It was just terrible and humourless. And long. 109 minutes of my short life on this spinning rock I am never getting back.

But even if a film is profoundly bad, a review must be fair to the hundreds of people who worked hard on it. There is usually something to recommend it, to stop it from being a one-star. Stardust is not poorly made; the cinematography and other technical aspects are well rendered. But they alone can’t make for an enjoyable watch.

Also, what I didn’t entirely take in during that interminable viewing was the baffling decision to cast actors decades older than the people they’re playing. Obviously I knew that Flynn was a dozen years too old (when filming took place, last year). But Jena Malone (35 playing 22) looks young. I hadn’t given a thought to how old Ron Oberman must have been back then: he was 28, Marc Maron was 56. There was one scene with Bowie’s manager, in which the character was so primly English I thought it was Ken Pitt (49 in 1971). It was not. That was supposed to be the charismatic, cigar-chewing Tony DeFries, who was 28 in 1971: the actor, Julian Richings, who looks like Pitt and looks nothing at all like DeFries, was 64. That was so unclear I thought it was a totally different person! And on it went with the Spiders: Ronson’s actor was 42; Mick was 25. The guy playing Woody was 38; the drummer was 21. (Trev Bolder doesn’t even get an IMDB listing)

Why on earth would casting directors take out the young, vigorous heart of a biopic and fill each role with actors all far too old? I had only noticed Flynn at the time – the rest made so little impression that their various levels of decrepitude must have passed me by. I don’t believe the filmmakers didn’t know how old these real people were: they chose not to care. That’s the level of detail and commitment to reality we’re talking about here.

Anyway, my review was well-received. People told me it made them not want to see the film.

The version below is 95% the same as the original. I have reinstated a couple of bits I felt were important and dropped back in a few extra details for colour. I’ve also added links to provide backstory, which isn’t the style of TO’s Film section but no harm in adding here.