Ronnie Scott's

Pharoah Sanders :: Ronnie Scott’s, London, 4-5-11

12/05/11 17:22 Filed in: Gigs

If you’re a pop musician you’ll never be cooler than when you were under 30. Indeed, the Beatles split before any of them reached that age. At the pinnacle of being respected and lauded, you’re told you produced your best work and you have a, say, 10 year purple patch before everyone starts saying you have nothing left to offer. And on comes the next bright young thing. With some notable exceptions, Radiohead spring to mind, being over 35 in pop music is a tale of raging against the dying light. Your audience gets old with you, you don’t attract fans who were your age when you started, your new albums are wheeled out to flog tickets for your tour, the only way you can make money now, and if you’re very lucky you won’t lose your jawline to chins, your waistline to elasticated trousers and your hairline to suspiciously placed hats.

You’re Van Morrison, Stevie Wonder, or Tom Jones; you haven’t made a decent record since the 70s even though your live shows are still worth going to, for nostalgia purposes only. You’re the Stones; you drag your excess skin out on the road for £125 a ticket. You’re Iggy Pop; with your ass hanging out, you look incredible and you do deliver live but it’s a schtick now, though it is remarkable that you’re alive at all. You’re Bowie; you’ve retired because after 5 decades of genius and, frankly, getting more beautiful with age, like Elvis should have but never did, you look a bit old now and you're too vain, and uninspired musically, to flog your hits anymore. Good for you. Better to give it up than be out there and phone it in. Then again, you might be Robert Plant; you don’t give a shit because everyone told you your career was over at 30 and you clawed your way back, using your voice in new ways, collaborating with peers and, lost looks aside (with the exception of resplendent hair) you get respect anew in your 60s. In popular music this is the dance, this is what you go through. And that’s if you’re already famous, your records are already owned and your gig tickets already sell, never mind if you’re trying to be heard in a sea of pathetic self-promotion and endless self-publishing.

However, there are genres, invisible to most, that don’t panic about their lack of attention, finance, talent shows, and all the other accoutrements that popular music is so desperate for. Metal is one, classical another, but, for the purposes of this, let’s talk jazz. You’ve heard it all before, that the musicians on stage have a better time than anyone listening, to paraphrase Tony Wilson. Marmite music. I think in order to appreciate jazz you do need to have an interest in musicianship, because, for wont of a better phrase, there is a certain amount of showing off involved. In terms of attending a jazz concert in the current era, where the great –tets of the past (Miles’ quintets, Monk’s quartet etc) are long gone, only a few of members of each generation remain so you get a fairly elderly figurehead taking on a group of session musos and doing what they know, what they’ve been doing for decades: getting out on the road in a different dark bar each night. But instead of what happens when old rockers go out on the road - at best, raking it in by filling a soulless arena with mums and dads revisiting their youth, or, at worst, eliciting groans from the critics bemoaning your tepid delivery while anyone in the first 15 rows winces at the state of your face - you’re faced by vibrant, thrilling sonic experiences delivered by men for whom age means they’re at the top of their game, not the bottom or, worse, the middle. Since improvisation is key, it doesn’t matter that the song might start out in the 50s, because it certainly comes round to the very moment in time that your ears take it in. Not that there’s no decent modern jazz being created, released and played, there certainly is, but that’s a whole other article.

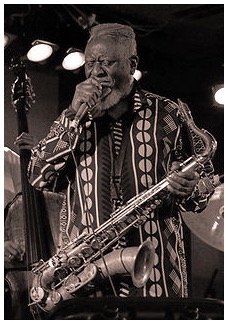

For once, you feel, the musicians are truly being respected. In rock, if you’re out there playing as a session muso for some dinosaur you’re happy to have the pay check, because you certainly aren't going to get the respect, perhaps because you’re often playing material that’s unchallenging. In jazz, playing with a remaining great, like Pharoah Sanders, is the pinnacle of your career. At 70, he’s playing more powerfully, with more skill and intricacy than he did in the 60s – when he was Coltrane’s favourite saxophonist. That’s some compliment. Described by Ornette Coleman as the best tenor player in the world, his lengthy, dissonant solos graced half a dozen Coltrane albums. In 1969 he released his masterpiece, the 30-minute free jazz blowout, The Creator Has a Masterplan. McCoy Tyner, Don Cherry, Sun Ra and more have all sought his playing in a career lasting 50 years.

I found it impossible to resist rushing to see him at Ronnie Scott’s recently. While the show was far from my first jazz gig, to my shame it was my first at Ronnie Scott’s. And what a venue, reminiscent of New York’s Village Vanguard; I had a little chuckle as I sat in the plush surroundings, surrounded by photos of jazz luminaries on the walls, low lighting, red table lamps, high-end fixtures and fittings and table service. You don’t get treated like this at a rock show. This was a long way from sticky floors and sweaty, beer-sodden gig-goers. I particularly enjoyed the body language of the table of couples in front of us – who had quite clearly picked Ronnie Scott’s on a random night, probably thinking they’d get some easy listening jazz to go with their bottles of white wine and birthday celebrations. The look on their faces as Sanders blew with wild abandon was a joy to behold. How wonderful that jazz can still horrify the tender-eared and inexperienced. It was an example of regular folks thinking they know what jazz is all about, then being shocked into silence by it. They should probably avoid Cecil Taylor.

What an honour, what a privilege to be in the presence of Pharoah Sanders. Accompanied by dazzling musicians – double bassist Mark Hodgson; pianist Jonathan Gee and drummer Gene Calderazzo – it was truly the most transcendent jazz concert I’ve witnessed. And this cool, charming pensioner blew everyone’s ears off, playing better at 70 than he did at 30. How refreshing to see a genre that doesn’t worship the young, but instead lauds achievement, and allows its members to actually get better with age. The very structure of jazz is designed to allow the artist to create something new with something old, and its demands are the opposite of rock music – slavish note-for-note recreations of hits are unacceptable. In an era of instant success, selling out arenas on one album, this show was a testament to well-earned longevity and timeless class.

...