Paul McCartney :: Hammersmith Apollo, London, 18-12-10

In some ways, he’s the very opposite of John, who put everything out there: good, bad and ugly. He was a work in progress and didn’t shy away from everyone knowing it; being incomplete, being painfully flawed, always searching for something, not even knowing what to look for half the time, was part of who he was and when he tried to be a better person, finding success or failure, he would never hide the journey. A confessional genre was born out of him, but Paul has never been like that. There are songs about heartfelt love, yes, but few (aside from Flaming Pie, when he didn’t know what else to do) about human flaws and personal frailty, which I always took as rather unappealing. Not that all singer songwriters must be confessional but, for me, if you’re not connecting with your audience on a personal level, there’s something missing. While songwriters with nothing to say can’t write words worth thinking about and self-absorbed lyricists mask deficiencies in song-craft, the perfect balance is one who can communicate on both musical and lyrical levels and I felt McCartney was sometimes lacking in the latter.

George would always talk about the Beatles as ‘them’, knowing the construct of pop culture iconography was something that shouldn’t be believed, something that shouldn’t stop you from looking for more. Paul, only half joking, once said that sometimes he would walk past the mirror and think, ‘you’re him!’ He and Ringo (who should be grateful, frankly) are satisfied with the tangible, whereas John and George always yearned for more. As such, with all the misgivings I have about his personality, I felt like a blank canvas as I trudged through the snow to Hammersmith to see him live, excited but wary.

After all that, you can guess what happened. He’s Paul fucking McCartney and he will work his arse off to make you forget every doubt you have about him, even if just for those two and a half hours on stage.

Some days I love the Stones more. Some days I love Led Zeppelin more. But they cannot make me feel what I felt last night. The Beatles are woven into the fabric of this country in a way that no other band is. These songs are your life; they’re in your DNA. I saw teenagers, hipsters, mid-30s couples, I’m-still-cool 40-year-old dads with their youngsters, record-fair guys like my dad pushing their late 50s and a collection of sweet old couples in their 60s who might even have seen him play this venue before, long before. And to a man, woman and child, every one of them laughed and cried and sang their hearts out, a deafening roar greeting every song. Strangers looked each other in the eyes with recognition of the moment. Those songs… there are so many - with that back catalogue, how can you go wrong?

The stars even aligned to the point where I ended up closer to the stage than my ticket allowed. I had a balcony ticket, but I was lucky enough to get to use what I call the ‘Arcade Fire trick’, only because I first did it for them at Brixton Academy a few years ago. You need two friends with standing tickets. They go in together. One comes back out with both tickets. You walk in with the spare. Simple. And thus, I ended up 10 rows back from the stage. Good work. Everyone was ready and wide-eyed, thrilled to be in such a small venue, thawing out from the snow, ready to feel or stay young, how they felt when they first heard, or their parents first played them, a Beatles song.

And not just Beatles songs either, there’s a lot of love for the 70s solo/Wings stuff – Band On The Run, Let Me Roll It, Jet and Maybe I’m Amazed were warmly greeted before massive explosions and fireworks, which I thought might set the roof alight, blasted out alongside Live And Let Die.

You simply lose yourself. There is no resistance; you can’t help it. These songs are part of who we are and, as you stand with a crowd of people who have come from all over the world, there’s an inevitable, inescapable, joyous, Englishness about every single person there. The Beatles make you feel, or rediscover, what it is to be English. Fifty years worth of people have grown up with this music in their head and, even in another fifty years, it’ll still mean as much. Undoubtedly, we’re in a lucky position now, to be able to hear these songs performed live. I saw him at Earls Court in 2003, a small figure in the distance, and it was a great show. Then I saw the next night and he came out with the same schtick, verbatim, between songs. I know your game, I thought. Everyone likes to think the gig they’re at, no matter who is on stage, is like a snowflake. Just for you, with your own touches and unique events on the night you went. And sometimes it is, but sometimes it’s not. And yet, with McCartney, despite yourself, it's just one of those things that you let simply float away with the opening bars of Magical Mystery Tour.

We got ‘em all – the innocence of youth (I Saw Her Standing There); Hard Day’s Night Beatlemania (Drive My Car/All My Loving); a Dylan-influenced lyrical move forward (Eleanor Rigby); solo in everything but name late-period rockers (Get Back/Back in the USSR), a little bit of quirky rubbish with good humour (Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da), weepy tributes (Here Today/Something); and so on and on and on. Songs you’d forgotten about completely, songs that remind you of being a kid, hearing them at home. Songs that you want to be the last songs you ever hear on this earth. And just think of some of the songs he can afford to leave out: Penny Lane, Can’t Buy Me Love, We Can Work It Out, Things We Said Today, Fixing A Hole, Fool On The Hill, Hello Goodbye, I’ll Follow The Sun, Here, There and Everywhere, Day Tripper, Lady Madonna…

He has everything to offer and, even if he knows it, it is irresistible. One need not be filled with humility when you can say you wrote Hey Jude and Yesterday. Hey Jude in particular is a tune we’ve all heard and over-heard. It goes on forever but, having lived through nine fake endings of Neil Young’s Rockin’ in the Free World, I could take it. So I sang and waved my arms and knew it might be the last time I’d get a chance to do it. Arenas and stadia are not for me, this was my night to have, to remember, to thank him for what he’s done. I sang Yesterday, and wept. And just when you think neither you nor he has any more to give, he plays Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, followed by The End and, with everyone joined as one, the meaning strikes home: and in the end, the love you take, is equal to the love you make.

Magical Mystery Tour

Jet

Got To Get You Into My life

All My Loving

One After 909

Drive My Car

Let Me Roll It/Foxy Lady (snippet)

The Long and Winding Road

1985

Maybe I'm Amazed

Blackbird

Here Today

I'm Looking Through You

And I Love Her

Dance Tonight

Eleanor Rigby

Hitch Hike

Sing The Changes

Something

Band on the Run

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da

Back In The USSR

A Day In The Life/Give Peace A Chance

Let It Be

Live And Let Die

Hey Jude

Encore 1

Wonderful Christmas Time

I Saw Her Standing There

Get Back

Encore 2

Yesterday

Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

The End

...

Zappa plays Zappa :: The Mighty Boosh Band – The Roundhouse, Camden, London, 6-11-10

With a character as large in life and who has lived as long in the memory as Frank Zappa has, it is fitting that a series of events celebrating his life and work could so dominate the Roundhouse this past weekend, the centrepiece of which was a Zappa plays Zappa performance. His eldest son, Dweezil, has been dutifully performing his father’s songs under that name, almost note for note, for years as his mother Gail wields a caring, but firm, hand over the great man’s legacy, pulling the strings from the California home they shared, which is still a living museum to one of Baltimore’s favourite sons.

The Roundhouse, a perfect venue, had been selected for a programme of celebrations to mark what would have been FZ’s 70th birthday next month. An art exhibition here, a Q&A there, the events culminated in a celebratory gig. Having released 62 albums during his lifetime, there was certainly no shortage of FZ material from which to draw. The crowd, highly knowledgeable, took this, quite acceptably, as their chance to pay tribute. Some, no doubt, never saw him perform for real; those present were the kind of audience I’ve seen so often – teenagers at the beginning of discovery, hipsters who’ve spent many a night talking rubbish while listening to Hot Rats and balding record-fair attendees reliving their 20s, who saw the real thing but aren’t smug about it.

The music FZ left behind was an encyclopaedia of the sounds he heard in his head – from doo-wop to jazz-fusion, from rock and classical to novelty. He might have smiled ruefully to note that his legacy in America is as someone remembered for arguing his anti-censorship-at-all-costs position, as a self-described ‘Constitutional fundamentalist’, on CNN (and in Congress) against the right-wing religiously-motivated moral guardians of the time (how little has changed) while getting his only hit with a bizarre tale of the dumbest Californian Valley Girls, featuring his then 14-year-old daughter Moon – who appeared to perform the song in the encore, joined by her adorable 5-year-old daughter Matilda, who shares Frank’s birthday. Being remembered for both music and politics is a legacy no-one would turn down.

It was a joyous, rather family-oriented, atmosphere. The musical pinnacle was reached upon the performance, in entirety, of perhaps his most complete album, 1974’s Apostrophe. These are classic songs – from the oft-heard Cosmik Debris to the rather normal, in context, and even moving, Uncle Remus.

The evening had started with a musically limited but game performance from a non-band – comedians the Mighty Boosh, lifelong Zappa/Beefheart fans, spent two weeks rehearsing, they said, for the show. Perhaps longer would have been a good idea, but that is their way: often appearing to indulge in little rehearsal and mostly getting away with it. They didn’t quite pull it off but it was a decent effort nonetheless, mostly due to their visible delight at having been included in the events of the weekend. They were well received and, in truth, I quite enjoyed their show (which would have benefitted from some visuals other than costume) until the ‘real’ musicians came on and, guitarist Julian Barratt aside, I accepted that heartfelt amateurism was the best they could offer. Still, they did employ Diva Zappa hidden inside Charlie, a pink, triangular, cowboy-hat-wearing, moustachioed, formerly animated, puppet made of chewing gum, which her old man would certainly have approved of.

One couldn’t help, however, sparing a thought for the path of the handsome Zappa family members. Being rock progeny is no easy task, since you can’t match up to your ancestry if you choose to follow the same medium. Even if you choose another outlet you’re still going to get compared to a figure you can’t live up to. However, there’s no doubt that Dweezil is a gifted guitar player, seemingly happy enough to recreate his music as a way of staying close to his father, and flexible enough as a musician to add his own flourishes along the way. Younger brother Ahmet is an ideas man in the Hollywood movie industry, which seems like a satisfying way of letting his original mind run riot. Moon, the oldest, is a sometime author/stand-up comedian and the youngest, Diva, who seems the most unaffected by the burden of Zappa-ness, is a painter and a creator of knitwear (really). Other people’s expectations don’t seem to affect them; they all seem happy enough. Not all of their contemporaries are as lucky. One might say an exception was Jeff Buckley, but his father Tim hardly reached the levels of fame that would weigh heavily and, sadly, he was only around to make one remarkable album anyway. It’s true that the McCartney kids have turned out pretty well, as has Duncan Jones, now an acclaimed filmmaker, who has flourished since his dad, Bowie, retired a few years ago.

But Lennon’s kids struggle, making unremarkable music, and the Stones/Rod/Geldof/Osbourne offspring just haven’t bothered at all (being a model doesn’t count) and have adopted the job of being socialites (one of the least attractive words in the English language). Whatever you do, you’re on a hiding to nothing. Use the name and you’re accused of profiteering, ignore it and the media press you on whether you resent your parents. Any talent you may have lives in their shadow. The Zappa kids seem remarkably level-headed, which is an achievement in itself considering they never knew what early bedtime was and their dad was away for six months out of every year. They’re all doing a bang-up job of keeping his memory alive in the right way, without attempting any projects that would have caused him to raise an eyebrow like he was hearing a wrong note on stage. Take note, Yoko.

One imagined the performance was how a real Zappa gig must have gone: complex, chaotic, disjointed, compelling and hugely enjoyable. I’ve rarely felt such warmth radiating from the audience to the stage and back. Once the fantastic performance of Apostrophe had ended the show did somewhat descend into a blizzard of muso noodling and guitar solos, as Dweezil was joined onstage by Scott Thunes and Jeff Simmons, who had played, at different times, with Zappa. Unavoidably, the best bits of the night were when the onstage band played with a recording of Zappa on the big screen, looming over us, as Dweezil puts it, from ‘grave to stage’. It’s a tough legacy to follow but one that is easy to honour.

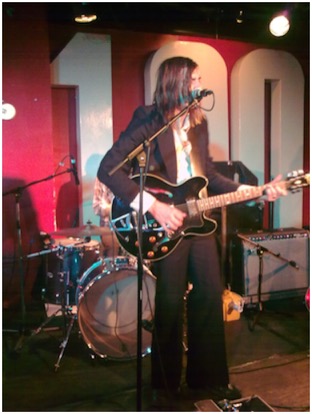

Dylan LeBlanc :: Josephine – 100 Club, London, 15-9-10

I’d planned to arrive late but by chance took a look at the 100 Club website and saw that the support was called Josephine – it turns out that this girl sounds like a cross between Tracy Chapman and Odetta and is from my very own manor, Cheetham Hill. Well. I had to see her. She was beautiful, charming, humble then confident, in possession of a superior talent for finger-picking and had a voice you could listen to sing anything. The songwriting was raw but all she needs is a proper break. Very impressive. In my life, I never thought I’d hear anyone sing a song about Cheetham Hill. I must have been the only other person from there in the room and it was a surreal moment, one that gave me an inner smile.

Thanks to Uncut, in any given month I will download at least ten albums that they have recommended in reviews or articles. Last month, they gave a fabulous review to Pauper’s Field, the debut by a 20-year-old Louisiana boy, and the son of a Muscle Shoals session musician, called Dylan LeBlanc. When listening, one can’t help but be staggered at how these country blues tales of regret and lost love, sung with a world-weary voice, over mournful pedal steel backings, could possibly have come from the heart of a kid barely out of his teens. A little Townes Van Zandt, a little Neil Young, with the delicate sonic and visual beauty of Nick Drake and Jeff Buckley, he seems out of his time. He’s already had a stay in rehab, confessed with bashful contrition in a recent Guardian interview, for booze and pills and you have to hope some marketing department doesn’t get hold of him and push him too far and too fast.

I remember the first time I heard Kings of Leon, a good, solid, no-nonsense band. And then I blinked and they got sucked into the machine; hair was cut, beards were shaved and they were made MOR. Except the drummer of course, you’ve got to keep one of them ‘dangerous’ looking since the PR company told you some of the target market wants a bad boy. The gritty, swamp blues-rock of their first album was long gone, replaced by Grammy-bland stadium pub rock. This is what can happen to musicians from the South; their God-fearing but happily hedonistic personas get boxed up nicely into something an X Factor Idol Who’s Got Talent auditionee can strain out. At least, since he’s signed to Rough Trade, I have hope that LeBlanc can get the guidance and support he needs without contrivance.

A vision of Southern charm, imbued with politeness and a fringe to hide behind, he gently walked onto the 100 Club stage to make his London debut. With a few pints to steady his nerves, he later confessed, it was only when he smiled shyly that could you see this was a lad who looks like he doesn’t shave yet.

At any other time, leading his band of hot rednecks, who look like they’re straight out of Bon Temps (think Sam Merlotte), he’s confident and turns out song after song of undeniable quality. The opener Low had a country strut, the ballad 5th Avenue Bar was played with tenderness on solo acoustic, he played Death of Outlaw Billy John with a nod to Americana and The Band and, even without the Emmylou Harris backing vocals, If The Creek Don’t Rise, with its epic swirl, had the small crowd enraptured. All of this while looking like a Massey Hall-era Neil Young.

The crowd wouldn’t let him leave, even after he’d thrown in a couple of covers – one by Van Zandt and a quite brilliant heavy blues rendition of Grandma’s Hands by Bill Withers – and he had to play pretty much every song he knew. It was a laid-back but compelling performance. A broken string here, a quip there, he was engaging, gifted and unique. One can only look forward to how good he’ll be when he’s 30.

...

Barbarism Begins At Home

Used by figures such as Churchill, Gandhi and Pope John Paul II, the quote above, or a variation on it, has its original roots in The Bible. Its invocation is designed to inspire us into action to help those less fortunate than ourselves. But one can’t pick and choose when it comes to which of those considered vulnerable is most deserving of our concern and care. If you work in a field where the goal is to gain greater understanding of, and provision for, special needs children or adults nowhere does it say that you can’t also find it in you to care for the elderly. If you devote time to raising awareness of, and building structural support for, those who are impoverished by geography and circumstance you can also fight for those who are denied decent working conditions by their employers. It might come down to a battle for civil rights, whether that takes the form of marrying the person you love or protecting the people around you from harm.

And if those in need can’t speak for themselves you can and should stand and speak for them. Another version of the quote, as Gandhi related it, is as follows:

“The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.”

When I’ve spoken about my concern for animal welfare in the past I have occasionally been met with rolled eyes. Animals matter less than people and wouldn’t my time be better spent speaking up about the welfare of children, workers and so on? As if I should have only a certain amount of concern to spare and as if it’s an imperative to rank causes of interest in order of socially accepted importance and then allocate time in the day one should give them. Is the welfare of my family more important to me than the life of an animal in a factory farm? Yes. Does this mean I can’t regale anyone who will listen with appalling tales of factory farming? No.

As a Western consumer, I’m fortunate to have a great deal of choice at my fingertips and a wise friend once told me that the greatest power you have is where you spend your money. Four years ago I chose to never eat another sentient being. Before then I never spoke out on animal welfare issues because I felt a hypocrite. That’s just me – there’s nothing to stop any carnivore from being active in animal rights matters.

My choice often provokes a curious defensiveness. I’m quizzed with suspicion on my choice of footwear material, whether I buy goods from China, eat Nestle products or avoid Nike. If I fall down on any of these standards I’m told that I’ve failed to live the life I preach about. I’ve never claimed that it’s possible to go through any given day without sometimes having to make regrettable choices: you just try to do the best you can. Defending one’s choices is part of trying to be a person of conscience, I’ve found out. However, I do notice that vegans never question me on why I’m not one of them!

I’m often asked if being a vegetarian is hard, if it’s expensive and (the classic) if I eat fish. I smile and say no to all three. The latter question is the most common, so much so that labels like pescetarian have been adopted into common language – as if eating a fish didn’t count somehow. Well, it’s not as cute as a lamb is it? Never mind that we’ll run out of fish to eat before we run out of land to raise lamb chops on.

By making these choices and talking about them, am I subconsciously telling those who make the opposite ones that their choices are wrong? I don’t mean to but perhaps I am. I’ve never tried to convert anyone to vegetarianism, but I don’t mind presenting information should the moment arise. I’m a bore to my family, telling them tales of animal cruelty I have learned of. But even in the delivery of information, sneaking it into family dinners or events, I do my best to take the McCartney family approach, even if I lean towards a cheeky Meat Is Murder reference now and then.

Morrissey, who guilted a generation into putting down their mince, is of the militant, aggressive variety of animal rights advocates. He doesn’t care if anyone listens, he doesn’t care who makes him an enemy and he doesn’t care if anyone agrees; he’ll say his piece regardless. He won’t bite his lip about any subject and certainly not about animal welfare – many of his own fans recoil in annoyance at his on-stage sermons about eating ‘flesh’ and animal experimentation. A kindlier polar opposite, Paul McCartney, appeals to the emotional and practical side – he stopped eating meat in 1975 upon seeing a happy lamb outside the window of his farm, he promotes healthy meat-free eating by continuing the pioneering work his late wife started with her cookbooks and cuisine and his daughter Stella has recently completed designs on the Queen’s guard’s bearskin hats in faux fur. This Morrissey Vs McCartney scale is the difference between the eye-catching and aggressive shock tactics of PETA (who certainly gain victories, if not friends, by the truckload) and the reasoned and intelligent campaigns of the organisation Compassion in World Farming.

A friend took me to a CIWF meeting last year and, while I do support and appreciate PETA’s stunts, from naked models to forceful lobbying, I found that the practical idealism of the CIWF lectures spoke to me. Their approach was simple enough. People are going to eat meat. Most will never give it up. But what they can be persuaded to do is find a moment to think about what they’re eating and how it arrived on their plate. At the CIWF lecture we were shown two side-by-side photographs of chickens, not yet matured. One had been raised free range, in a farm’s outdoor space, and the other in a wire cage. The difference between them was clear to see. One had bright, abundant feathers and sturdy legs; the other was considerably bigger, with paler feathers and bent legs. Due to being injected with hormones, but denied outside roaming, the bigger bird would provide more meat but could not hold its own weight. Any larger and its legs would surely break. It was then that I realised that I was being given the information on how to appeal to people who were fine with breaking this bird’s neck and eating it. Do you really want to eat a chicken stuffed full of hormones? Or a cow injected with a mystery serum to make it produce more milk? It’ll taste better if it’s had a good life, I started saying, with plaintive persuasion, to those around me.

It helps my case that the British public is, on the whole, a compassionate nation of animal lovers. One can’t imagine this country tolerating a condition I read about on a farm in Japan where, to prevent the pigs from moving in their cramped cages, a metal spike was speared through their jaws to keep them stationary.

Of course there are endless issues to address: animal labour worldwide in zoos, circuses, bullfighting, horse-racing and more; the passion for hunting that some barbaric sections of, among others, Africa, America and Canada still have; the status symbol dogs that I see far too often in the UK and the now sadly resurgent appetite for the fur industry. It would certainly also be desirable to break the hold that cheap, poor quality fast food has but doing that would be partly connected to breaking the hold that cheap, poor quality booze has and that, I fear, is a mission too far!

It is the issue of factory farming that is most easily addressed and prime for legislation and change.

So can we all agree on one thing at least? That if you must eat animals they should be treated well before slaughter. If you’re going to eat them, why not avoid torturing them during their short lives? Of course, there are different levels of torture. There’s being kept in cages, never seeing the light of day. There’s being mistreated by workers at slaughterhouses before the throat-slitting day comes. But there is only one delicacy that has physical torture built into rearing: foie gras, recently described to me as ‘animal water-boarding’.

The literal translation of foie gras is fatty liver. Mostly produced in France, it is made from ducks and, to a lesser extent, geese. For a few weeks prior to slaughter, the animals are subject to gavage, French for ‘to gorge’. In short, it’s force-feeding. A tube is inserted into their throats and two or three times a day they are pumped full of boiled maize and fat, in order to increase the size of the liver by up to ten times, which then leads to production of an expensive and, I’m told, delicious meal. After this process many farms then put an elastic band around the animal’s neck to stop it from throwing up the food.

During the rearing period, it’s possible that some of these birds may have access to the outdoors but not enough to produce their natural behaviour. If they are allowed outdoors, they can forage for food but are not given any other food before the force-feeding begins. However, it’s more likely that they are confined in tiny cages, day and night before being slaughtered at six months old. This force-feeding in human terms would be like having 45 pounds of pasta pumped into your stomach every day. It’s cruelty, it’s torture and for what? So posh restaurants with pretentious menus can serve it to their customers.

Force-feeding for foie gras production is prohibited or prevented by general animal welfare legislation in many countries, including most provinces in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. EU laws that allow free movement of goods mean importing it can never be banned so a consumer boycott is the only option. The following places, in London alone, still serve it:

http://www.squarerestaurant.com/

http://www.odettesprimrosehill.com/

http://www.thewolseley.com/

http://www.comptoirgascon.com

http://www.capitalhotel.co.uk/

http://www.le-gavroche.co.uk/

As Harrods continues to sell foie gras, chains such as Selfridges, House of Fraser and Harvey Nichols have banned it. AirCanada, AirAsia, Virgin, United, Delta, SAS and KLM have removed it from their menus. It has been removed from menus at all royal functions, thanks to Prince Charles. Sainsbury’s, Marks & Spencer, Morrisons, Tesco, Whole Foods and Asda will not stock it while Waitrose sells CIWF-approved ‘faux gras’. And thanks to Tamara Ecclestone, PETA’s foie gras campaign ambassador, it has been removed from the menus of Formula One teams such as Williams, Cosworth, Mercedes, Red Bull and Lotus.

I’m sure foie gras tastes great - people wouldn’t eat it otherwise. The choice is your stomach or your conscience. Whether you love animals or couldn’t care less about them, anyone with an ounce of compassion shouldn’t sanction and participate in this kind of cruelty.

http://www.ciwf.org.uk/

(all photos from www.ciwf.org.uk)

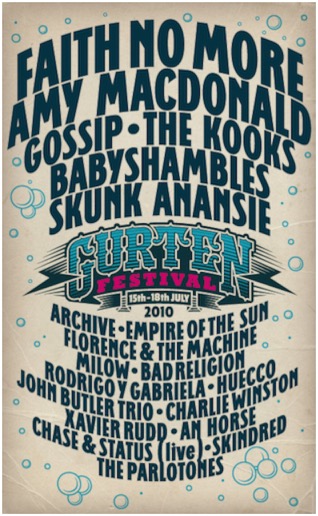

Editors :: Faith No More :: Rodrigo Y Gabriela :: Gossip :: The Cribs :: Charlie Winston – Gurten Festival, Bern, Switzerland, 16-7-10

Firstly, it was on the top of a mountain, accessible only by a long uphill walk (I think not) or a cable car (yes please). Festival attendees are universal; they’re all looking for the right weather, bands, facilities and vibe. Unsurprisingly, there was a large amount of beer being downed but still nothing compared to Brits, I’m embarrassed to say. Drinking is a sport in the UK; the only aim is to get as wasted as possible. As I surveyed the happy tipsy crowd, they were actually enjoying a drink without hurtling toward the final result, they weren’t hoping to pass out on the grass or wear a volley of vomit as a badge of honour - they just wanted to have a good time.

At the bigger UK festivals performances come with a certain pressure. As TV broadcasts bring self-consciousness to some acts, the critics sharpen their knives as the seen-it-all main stage crowds wait for hits. At a larger festival you have dozens of stages and hundreds of acts to discover away from the main stage pressure but at smaller gatherings an intimate (for a festival) setting can often bring out the best performances.

I suspect many of the smaller European festivals are like Gurten - refreshingly unpretentious and free of the weight of expectation and media pressure. Not that the festival isn’t publicised or given radio/TV coverage, but the attention is national, rather than international. Taking the pressure off further is that Gurten is the smaller relation compared to the legendary Montreux Jazz Festival, finishing up just as Gurten starts, and the larger Paleo Festival, taking place in Nyon, near Geneva, all this week. As a result, the bands clearly feel much freer than when they’re under the make-or-break microscope at Reading/Leeds, V, Wireless, Isle of Wight, T in the Park, Glasto et al.

The performances started with British singer Charlie Winston, completely unknown here in the UK. His easy manner (a likable Jay Kay, if that’s not beyond the realm of imagination) and unfussy songs recall Paolo Nutini. He’s very popular in French-speaking countries, it would seem. It made me wonder how many other British singers there are plying their trade in Europe, achieving considerable success without anyone here noticing. A little cheesy but undoubtedly talented, he was a mildly diverting opening act in the burning sun.

It was at that point, as people looked to their show guides to see what was up next, that I realised something was different. With larger festivals the acts are on different stages simultaneously. People are made to make choices and, while they may go for a food/drink wander between bands, the crucial aspect is that not everyone is doing this at the same time. Not at Gurten. There were three stages, a small one with regional acts, a larger tent and the main stage.

As such, the acts in the larger tent and on the main stage were scheduled not to coincide. The advantage is that no one misses a band they want to see and a short walk between stages ensures you can see every band. This also means you can get to the front easily for any band, should you leave the previous one a couple of songs early. The negative side of this is everyone is doing the same thing, all the time. Everyone goes from one place to another, together. It’s a little crazy. Massive queues for food and a bottleneck formed as everyone tried to get to the other stage for the next band. With limited space, it was a little difficult to move around but the crowds were so good-natured and friendly that you just went with the flow. As an aside, the loos were like luxury compared to what I was used to. Separate ones for men and women; toilet paper, even flushing! Partly, this civilised atmosphere is due to a lot of day tickets as well as campers. Since it’s near the city centre many choose to come for the day and go home.

After Charlie Winston we made our way to see The Cribs. I saw them at Glasto a couple of years ago, out of devotion to Johnny M, and was disappointed. This time they were much better; good punk pop with better songs than I had remembered – or perhaps, their more recent album is a vast improvement. Pretty good but another band beckoned – we strolled back to the main stage to see Gossip.

Admittedly, they do have a schtick; Beth Ditto’s southern charm and powerful voice connect with the crowd instantly and the minimal electro pop is well played with a fair few hits sprinkled throughout the set. Without guile, without self-consciousness, she is a supremely entertaining leader. The crowd was well up for it and bounced happily to Heavy Cross to close the show. You know what you’re getting with Gossip but, I must say, I enjoyed the performance immensely. As evening turned to dusk, everyone rushed for food - a limited selection in truth but by then, a few beers down the line, no one seemed to care. We went for a little walk around the larger part of the site, browsing at the myriad stalls selling clothes and trinkets. We still had time for some heavy flamenco guitar in the form of Mexican duo Rodrigo Y Gabriela. They do get the crowd going, which considering no one knows the songs and everyone is simply recoiling in admiration at the musicianship is impressive. The last time I saw them they played songs by Metallica and Pink Floyd but we were keen to get a great spot for the real reason we had been so excited to come to Gurten: Faith No More. As such, we made a quick exit before the encore and rushed back to the main stage.

I’d seen Rage Against the Machine recently so it was fairly amusing to be faced with another band of my youth so soon. Quickly gaining a place at the front, I was delighted to see them appear, in matching lounge suits, and power into From Out of Nowhere. They had reformed a year before, playing festivals including Gurten, and you sensed that Patton had been on the road for long enough. As a man who creates as much unusual material as he does, you could sense his slight bitterness at the lack of interest projects like Lovage, Mondo Cane, Fantomas and Mr Bungle generate in anyone but his hardcore fans, compared to the collective muscle memory reception given to these 15-20 year old songs. Growling and throwing himself around the stage, but hitting every note, he was almost a parody, if an entertaining one. My companions, who had seen FNM the year before, said the difference was marked, in terms of his tiredness. I suspect the reunion will last long enough for him to fund his next project. Despite this, the songs have lost none of their power and he gave it his all, that’s in no doubt.

Noticeably, rather than a RATM type collective, FNM are very much a band with one leader. Stage diving, he was lifted up to surf, only to be dropped several times, before he made it back to the stage expressing mock annoyance at the crowd for dropping him. Taking over a camera operator’s job he fell again, only to get back up, headphones still perfectly in place. Daft and likable, he elicited a great deal of affection from the crowd.

Billy Gould, Roddy Bottum and Mike Bordin were animated and rock solid throughout, Bordin in particular being impressive, as always. Guitarist Jon Hudson, despite being on their last album, performed competently but came off like a session player, adding nothing in the way of stagecraft or passion. I would imagine he’s in the band precisely for that reason - because he’s no trouble. I can’t see them creating a song like The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, also played, about former guitarist Jim Martin, about him. All the songs you’d wish for were played – Be Aggressive, Surprise! You’re Dead!, Epic, Midlife Crisis, Easy and set closer We Care A Lot. It was a powerful, breathless show received by a rapturous crowd.

As the crowd dispersed to find more drink and then reconvened for Editors, strolling back a few songs in, I realised what a headlining-non-headliner was. Everyone had used their energy on FNM, which felt like a headliners set – a lukewarm reception was all they had left, and wanted, to give. Considering their well played but ultimately fairly dull songs, fronted by a third rate Ian Curtis tribute singer whose voice could put you to sleep, this was no surprise. By then, at nearly 2am, my legs ached and, having not slept for a couple of days, I was ready to make an exit and leave the masses to their all-night party. Off we went, a crush for the cable car down reminding me that Germans (even if they’re Swiss) aren’t big on forming a queue. It was a unique experience and one that I would be happy to repeat.

...

Kick and rush, 16-6-10

But were we ever able to leave kick and rush? In reality, how many players really does Capello have to choose from to make his squad? No-one doubts that he has picked the best 23 players to take to South Africa. And no-one doubts that most of the first 11 would walk into any Champions League team - individually. Collectively, they're not up to much. Of that reported 38% how many of those should be considered good enough to play for the national team anyway? Many of the poorer, in terms of ambition, talent and finance, clubs in the PL have no choice but to employ average English players. Bolton, Blackburn, Wigan, Sunderland, Fulham even. These are teams who have English players but ones that no-one would argue are good enough to grace Capello's squad. It's hardly like he has 50 or 60 players to choose his 23 from. It's more like a good 35 and decent enough 28 leading to a very good 23.

So let's blame the ball. The Jabulani, the perfectly round (what were balls before?) Adidas made ball that is now being used at the WC has been steeped in controversy. England cannot use it in the PL - a deal with Nike prevents it. England cannot use it in internationals, a deal with Umbro prevents that. But for those nations with Adidas sponsored leagues and teams - Switzerland, Argentina, France and Beckenbauer's Germany - have all been using it since February. I've watched goalkeepers fumble that ball for the last week and the ones that survived did so because of their positioning. Get your body behind the ball and you can fumble it, you'll still probably be alright. Crucially, Rob Green didn't do this. And he's been doing it all season for West Ham, his positioning is to blame - not the ball. We're even getting desperate enough to blame the altitude though I cannot figure out why the Germans, the most impressive team so far in the tournament, are training at sea level and England are training nearly 1400 metres above it. Their first match, at sea level, was almost perfect. If we're training above sea level to make later tournament games easier that's all very well but what if we're knocked out before then?

We fear heartbreak in England and history tells us it is coming. It's our own fight, our own stubborn resistance, our own uniquely English attitude to being beaten by the better teams that has actually harmed us in tournaments. We never just lose 2 or 3-0 to Portugal, Argentina, Germany et al. It might help if we did. It might force us to confront the deep seated issues that have damaged English football in the last 20 years. Is it any wonder that managers such as Wenger are claimed as geniuses? His professorial approach to training and living has changed Arsenal forever - but he chooses foreign players to carry out his visions and this cannot be a coincidence. English players, from childhood, are trained with outdated methods. Commerce rules in the PL and the expensive foreigners have been brought in to make our league the greatest in the world - precisely because the cloggers and bulls who populate the Bolton's and Blackburn's aren't going to put bums on international TV seats.

But we are English, we fight harder than anyone else. Surely no-one can claim that no less than five major tournament exits of the last 20 years via penalties are down to coincidence? We have not been beaten easily, we have fought until the last seconds against better teams and taken them to penalties. And then we lose, the nation weeps and bemoans nothing more than bad luck. It's this failure to lose fair and square, this peculiarly English desire to fight until the last penalty has been taken, that has led to our failure to truly assess why we keep failing at tournaments. It's because of bad luck, people cry. No, it's not. The penalty strewn, heartbreaking exits are the real smokescreen.

We are a nervous nation that awaits our World Cup 2010 fate. We know it will happen again. We know we will scrape to the quarters, play a decent team, fight with all our might, defy the odds with passion and hunger, bely the greater skill of our opponents and lose in some heartbreaking fashion. And rather than blaming the PL, the FA, the training of kids playing football from youth, the manager (we now have a good one, can't blame him) we will throw up our hands and say what bad luck! Again! And we'll go right back to our expensively assembled PL teams, who, if we're all honest, we care far more about than our national team. We'll just accept our failures, with a catalogue of excuses about cheating opponents and bad luck. The PL is worth so much money it's too far down the road to change, despite the cap being brought in on homegrown players. That won't change the infrastructure, how they're trained. Our first 11 might be able to walk, individually, into any CL team. But they aren't up to much all together. How will we exit the WC this time round? Who will be the villain? As ever, we will blame the penalties and close our eyes to the real reasons.

...

Rage Against The Machine, Finsbury Park, London 6-6-10

So, when Jon and Tracy Morter started a Facebook campaign to get a Rage Against The Machine song to challenge the X Factor/Pop Idol dominance of the Christmas number 1 slot the prevailing feeling was that it wouldn’t work, how could it? How could a country that expects something for nothing, whether it’s in the pursuit of these X Factor golden tickets or the reluctance to pay for media, be motivated into dropping their apathy?

The campaign was grass roots; rationally, it had no chance against the multi-million pound ITV-powered exposure of the X Factor. But a funny thing happened. It turned out that as many people as there are lapping up paparazzi-fuelled, reality TV drivel and endless celebrity magazine coverage, there are just as many who not only exist completely outside that world but also were looking for a way to protest against it. There are those of us, even if we’re unable to avoid the cultural proliferation of it all, who don’t watch these shows nor buy into the voting/buying follow-up aspect, and we felt strangely compelled to support this Facebook campaign. By our thousands we downloaded, and no doubt some people were doing so for the first time, the anti-corporate anthem Killing In The Name.

To be part of something that for just one moment defeated the Cowell machine, all cynicism aside, felt undeniably good. The Christmas number 1 race, whether it ended with a cheesy pop hit or a novelty record, had at least always been interesting, a laugh. Now with X Factor et al the race had been destroyed for five years on the run. No longer. More than half a million souls bought that RATM song and proved their point. The promised gig, last night in Finsbury Park, brought 40,000 together for a victory party. It had a Reading Festival feel, with its stalls of endless no quality fast food and poor facilities. It was no Glastonbury, with its veggie burgers and Hare Krishna tent. This was a booze-sodden public space, overtaken by metalheads, current and former, and kids likely born after the 1992 release of the band’s first album.

The conquering heroes from Los Angeles took the stage as evening became night, powering through a flawlessly chosen 75-minute set – Bulls on Parade, Bullet in the Head, Freedom, Bombtrack, Testify – and those monstrous bass-driven riffs felt as powerful as they did 18 years ago. For me, and I suspect many others, there was a sense of youth reliving, having found that first album to be an unwavering accompaniment to my teens. Each member of this muscular and powerful band connected every sinew and thought to each other and the audience. I’ve never heard an outdoor gig sound as good.

I’m sure record labels, themselves raging against the dying light, and PR companies will try to harness the lightning in a bottle campaign and copy it, in a futile attempt to con the public into doing this every year. But they won’t pull it off. The internet has been harnessed many times into creating a buzz about films or flash mobs but it never felt like this before. A band most people in our culturally deprived and tabloid-fed nation had never heard of were made into household names almost overnight. It was a campaign free of guile and agenda, which won’t be repeated in quite the same way again.

As the main show ended and the crowd roared their approval, a short film, accompanied by the losing song, appeared on the screens, telling the David and Goliath tale, complete with quotes from the poor lad who won the X Factor and lost the bigger battle. Who will remember him another 18 years from now? He’ll be a footnote, along with the other ‘winners’ of these shows. The encore performance of Killing in the Name was utterly triumphant, the perfect end to a brilliant show. RATM have always prospered as outspoken advocates for the power of the individual. They had their victory, and we had ours.

...

Rufus Wainwright, Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, 13-04-10

The stage stayed dark, save for a single spotlight over him. Flanked by scenery from his own opera, Prima Donna, playing currently, he weaved melodies from his own hand, Shakespeare’s sonnets and a French libretto. A ten-foot coat train draped behind him stretching half way across the stage, as the visuals of Douglas Gordon gently unfurled on a cinema size screen. Known for his Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait film, a real-time study of the graceful, balletic Frenchman playing for Real Madrid, he took film of Rufus’s eye, clad in make-up, black oils and a silver tipped false eyelash, and played the footage back in slow motion as the large eye, or several smaller ones, opened and closed. At the surprising end of his Zidane film, the master fights his way into a red card. As Rufus played the last song, Zebulon, a tale of an imaginary childhood friend returning to witness adulthood, a bulbous tear collected in the on screen eye and slowly made its journey, as tears do. I wiped my own tear, not for the last time in the evening, and took pause as he again slowly walked off as the curtain fell and the applause was finally allowed to rise. With a wonderful absurdity and a theatrical pretentiousness that somehow didn’t feel unwelcome, it was quite simply one of the finest and most moving performances I have seen.

Recorded a month before Kate McGarrigle’s death in January, All Days Are Nights has inevitably taken on the role of songs mourning the end before it came. That he gets out there and plays these songs feels like part of the recovery process, with emotions open and raw. That’s always been the way in his family, gladly beholden to their folk tradition. Intimate feelings are poured into songs, be they complimentary or vicious. The song Martha exhorts his sister to take over the matriarch role, as something she must do, hers to make in her own image. Dinner At Eight, performed in the second half, is a devastating, sad tale of child abandonment and plea for remorse directed at their father Loudon. Now Kate has gone the healing of parental relations seems to have begun, with that song the last, you hope, of the most brutal of judgements.

Coming out for the second half rather more modestly dressed, Rufus was visibly relaxed, performing songs of great beauty – The Art Teacher, Poses, Vibrate – for the assembled crowd. Always a bundle of nervous energy he riffed on the noticeable blue plaques in London, given to notable residents: “I need one of those… or a statue maybe!” He is a curious mix of extreme show-off and goofy joker, welcomed with great affection by his audience.

Taking two encores, the setlist spanning all of his recorded work, he warned us that what was coming, The Walking Song, was by his mother and an example of her being the most talented of the family. It was beautiful and, since he has elected to perform it nightly, it brought the outcome one might expect: he made it almost to the end without breaking down but upon singing “We’ll talk blood and how we were bred, talk about the folks both living and dead” he could hold onto his concentration no longer and, with cracking voice, it rumbled to a quick halt. He stood, wiped tears from his face, and took a bow. One final note of brightness, the first song from his first album, Foolish Love, ended the proceedings.

He pushes himself harder than ever at a time when he’s most vulnerable, inviting us to intrude on his grief. Public mourning is very often painful to witness, and it was, but one could not turn down the invitation of going on the journey.

Who Are You New York?

Sad with What I Have

Martha

Give Me What I Want and Give It to Me Now!

True Loves

Sonnet 43

Sonnet 20

Sonnet 10

The Dream

What Would I Ever Do with a Rose?

Les Feux D'Artifice T'Appellent

Zebulon

----------------

Beauty Mark

Grey Gardens

Matinee Idol

Memphis Skyline

The Art Teacher

Poses

Vibrate

Little Sister

Dinner At Eight

Cigarettes And Chocolate Milk

Going To A Town

Millbrook

The Walking Song

Foolish Love

...

Suede, Royal Albert Hall, London, 24-03-10

Your heart was consumed by it but your head knew it was fleeting. It was the difference between childhood crush and adult love. Transpose that to music and my crush was Bowie. Then in ’93 he released an album I didn’t, and still don’t, like. He took his eye off the ball and Suede swooped in to take advantage. He got me back in ’95 but Suede had taken hold by then – maybe they did it so easily precisely because they were so in thrall to Bowie too.

The press, as is their way, built them up and then rubbed their hands in glee when Bernard Butler left and their sprawling, insane, brilliant second album Dog Man Star, and its preceding single, Stay Together, fell into wreckage. But Brett Anderson had always been stubborn, he recruited a 17-year-old Suede fan to replicate those guitar parts perfectly and then the press had to shut their mouths as the band produced their most successful and hit-packed album, Coming Up, in ‘96. Anderson/Oakes wrote better pure pop songs than Anderson/Butler. They weren’t ambitious but they were irresistible.

I was there until the bitter end, seven years ago, as they bowed out with the forgettable A New Morning. And then, at the Royal Albert Hall this week, I found that most unimaginable of things – the band I cheated on my crush with had not been dimmed by age and the ardour I felt had not been extinguished by the passing years. I pondered aloud, on these very pages, in a Brett Anderson review in January whether youthful love had blinded me. That in adulthood I feared finding the music dated and shallow, unable to stand the test of time.

Half way through the show, after a breathless Metal Mickey, the applause carried on, and carried on, until it became a full standing ovation. One by one each of them broke into a smile, finally stopping the breakneck pace of the show, and started to take in the wave of love and gratitude coming at them. Even the impermeable Neil Codling, on guitar and keyboards, broke rank. Always a Suede song made flesh, all pale glamour and high cheekbones, he broke character and took in the moment, his first Suede show for nearly ten years. Solid and cool on bass and drums, Mat Osman (now a magazine editor) and Simon Gilbert (living in Thailand, now a member of punk rock band Futon, big in Asia apparently) joined him, exchanging smiles. Richard Oakes, the teenager who never felt the weight of what he was replacing, remembered that the first gig he went to was Suede. He made this possible.

A contented smile covered Brett’s face, visibly overwhelmed by what he had not felt for years. His more self-conscious moves gone, he had retaken the vibrant leader role and made it his again. He still knew how to do this, becoming the focal point of the collective energy of both band and audience. He revelled in it because he hadn’t spent the preceding seven years chasing it.

We jumped and sang and rejoiced, but that was the thing, I wasn’t reliving my teens. It was all happening now, right now, it wasn’t some flashback – this music was still great. Everyone felt it and it was better than when we were young, as if none of us had aged.

I saw them at the Manchester Apollo in ‘96 and given that Coming Up was the first record they’d made with Oakes writing and playing, it was deemed best to not play anything from the first album. They did play some of Dog Man Star but Animal Nitrate et al were too hard to face. I never did get to hear those debut album tunes then but there they were in 2010, we heard it all - B-sides, album tracks and hits.

They could have gone on for another half hour playing songs there were no time for – We Are The Pigs, Still Life, My Insatiable One, By The Sea, Sleeping Pills and Stay Together (never likely, the band disowned it when it came out). But nothing like that mattered. Everyone just forgot how the years had passed, how we’d all grown up, how we were tired of our office jobs, and we let the music do what it does.

The press wrote them off as foppish posers, after once declaring them the most exciting band in England, and they never got the respect they deserved. No more. It was undeniable. A childhood crush lasts forever; it stays with you, frozen in perfect time. But your first love fades, as it’s supposed to. Sixteen years have passed since my first love. I imagined what it would be like seeing him now, still looking the same as in ‘94. My heart would jump; there would be no letdown. It would still mean everything.

She

Trash

Filmstar

Animal Nitrate

Heroine

Pantomime Horse

Killing of a Flash Boy

Can’t Get Enough

Everything Will Flow

He’s Gone

The Next Life

Asphalt World/So Young

Metal Mickey

The Wild Ones

New Generation

The Beautiful Ones

The Living Dead

The 2 of Us

Saturday Night

Them Crooked Vultures, Royal Albert Hall, London, 22-03-10

It’s the 10th anniversary of the Teenage Cancer Trust, the charity set up by Roger Daltrey, who introduced the band with his customary East End swagger. Having block booked this very week a decade ago, to ensure an uninterrupted series of gigs at the venue, the Hall shuddered, bounced and blasted my ears to shreds. It must have been the loudest show since Led Zeppelin played there in 1970. After about 45 minutes I thought the sound lost something, either the band lost a little energy, which wouldn’t be anything to be ashamed of considering the pace they started at, but then I realised it was just the ringing in my ears.

With one hour-long album out, it took some magic and a couple of new tunes to make a great 90 minute show - but that’s what it was. It was completely without pretension, guile, artifice and calculation. They just enjoy it, there’s no more to it than that. As you might imagine, with a combined age of 135 for the three core members (Mere babies compared to The Stranglers, then - Ed.) and decades of playing to their names, they were tighter than most bands I’ve seen.

It was hard to take your eyes off Dave Grohl. Not just because it’s a pleasure to see him behind the kit again but because he’s a compelling figure, a talisman now as close to Bonham as anyone will ever get. Josh Homme’s voice and playing are perfect, his persona the epitome of tough West Coast cool. He even did a little shuffle dance during Interludes With Ludes, an almost swing track from the album and the only guitar-free song on offer. Grohl and Homme are doing this really to fulfil a childhood dream; that much is obvious. They don’t want to let John Paul Jones, always classy and still lightning quick at 64, down and they’ve made a record together that stands beside the best of Plant’s solo output. Sure, there’s a bit of filler on it. But when they get it right – New Fang, Spinning in Daffodils, Caligulove, Gunman, Mind Eraser No Chaser – those riffs are big enough to stand up to anything they’ve made before.

...

Grizzly Bear & Beach House, Roundhouse, London, 14-03-10

How many kinds of gigs are there? There’s always a mate’s band and if you’re lucky you won’t have to pretend they’re good. You’ll see overhyped bands in underground clubs with foot-high stages and variable outcomes. You’ll tolerate arenas or stadia to see the artists who’ve always meant the world to you and you’ll feel the pang of songs that have been embedded into your consciousness. For the amount you’re paying these days, 50 quid up, it should be worth it. You might take a chance and find a show unexpectedly enjoyable, not to mention eccentric (as I did last week seeing bass legend Les Claypool – more avant-garde jazz funk experimentation than you could bend a Larry Graham thumb at).

The better experiences last in the memory at least until the next gig. But if, by some miraculous alignment, you combine good judgement and luck on a particular night, you witness a show that you know you’ll be talking about for years to come. I felt that way the first time I saw Arcade Fire, when I knew not one of their songs, in May 2005 at the Astoria. And I felt that same way last Sunday, as I stood in spellbound shock after Grizzly Bear’s last chord had faded.

More of a double bill than a support slot and headliner, I also can’t remember enjoying an opening act as much as I enjoyed Baltimore’s sublime Beach House. I swooned as French-born Victoria Legrand’s soaring, sonorous voice reached into every nook of the Roundhouse’s columns and circus-top roof. Their new album, Teen Dream, one of my favourites of the year so far, resurrects a Cocteau Twins dream pop feel I thought was lost a generation ago. Mac loops, jangly guitars, keyboards and that voice: it won’t be long until they’re filling the venue by themselves.

And so, to Brooklyn’s Grizzly Bear. Where on earth do these songs come from? Walls of dense noise, musicianship connected on a cellular level, climactic epic sounds, gentle psychedelic pop floated up to the Roundhouse balcony as lanterns flickered across the stage; all this from four young men who play without displaying any of the arrogance that should be inevitable in a band this good. When you think of how much praise powerful but derivative acts like Kasabian get, you feel like shaking record (CD/digital) buyers by the shoulders and saying come on, listen to this, music can be so much more than the pedestrian big-chorus-and-nothing-else Kings of Leon/Killers rock we’re all being force-fed. It can be more than churned out formulaic electro or Cowell-created packaging. This joyous magical music comes from the Radiohead end of that spectrum – no wonder they’re Jonny Greenwood’s favourite band.

Veckatimest was 2009’s best album, a headphones record that washes over you, a sonic pleasure. The show as a whole and the performance of those songs improved on recorded perfection. I just stood there in shock, taking in the harmonies and the instruments – yes, drums and guitars but also a Rhodes organ, flute, clarinet, glockenspiel and Autoharp – as it all went by in a haze. It was a special night and everyone there knew it. Some say all the chords have been used, all the great songs have been written. Not for them. It felt like a step forward.

Midlake, Shepherds Bush Empire, London, 18-02-10

Midlake, a few EPs and three albums in, are just now able to play venues the size of the 2000 capacity Shepherd’s Bush Empire. Allowed to make a couple of albums while no-one noticed, they are now ready and moving at their own pace, growing in experience and gaining a fan base at a comfortable level. Now expanded to a seven-piece live, their chilled psychedelic folk rock was a charming way to spend an evening. There’s something undemanding about them, almost forgettable. But you sense they’re the kind of band who’ll start making their best records at album five or six. That’s how it used to be – some of the best artists you can think of, from U2 to Tim Buckley, made several albums before anyone noticed. Albums were made quickly, and to a budget, so that a label weren’t going mad at the studio bill and the artist didn’t find themselves deeply in debt to a label unwilling to take chances on them or anyone else in the future. Now albums can be self-made in a home studio as good as any you can record in. This recording freedom is death to big labels and relentlessly invigorating to everyone else. Midlake took 18 months to make their new album, The Courage Of Others. A decade ago they wouldn’t have had a chance. A beautiful grower of a record, they played much of it last night to a typical London crowd.

By typical, I mean everyone found it hard to shut up and stop moving around constantly for drinks. People treat gigs like they’re in a pub. You don’t notice it when you’re at the front, because those that surround you are committed to the artist. Arriving late, I was at the back, constantly distracted by the search for booze and inane chatter. But as the gig wore on everyone started to focus, realising this band were working hard up there and deserved more attention. And of course, they had started playing songs the audience knew, from 2006’s breakthrough album The Trials of Van Occupanther.

They’re what I’d call a Whistle Test band. They look young, laid back, long- haired, wear a bit of flannel and indulge in the odd jam. Not too much though, it was all tightly played, mostly through their four minute folk pop gems. CSNY harmonies backed by post-Green, but pre-Buckingham, Fleetwood Mac. They might have listened to a lot of what leader Tim Smith has called ‘fair maiden’ music (meaning Fairport Convention and the Pentangle) but fortunately their sound remains relatively untouched by that particular kind of British folk sound, which is a relief to my ear. It was an undemanding but enjoyable night and it’ll be a pleasure to see them find their feet in the next few years.

...

Brett Anderson, Shepherds Bush Empire, London, 22-01-10

Uncertainty aside, I came to think that they deserved better and more recognition as one of the great British bands of the 90s. They were the first band to be on the cover of Melody Maker before they released a song and were promoted straight to the cover of the NME at pretty much the same time. The knives were out but when The Drowners arrived, the critical praise and frenzied acolytes poured forward. I remember watching them on the Brit Awards; Brett struck that androgynous chord with me that Bowie had done some years earlier. Shaking his hips, whipping the mic-lead, with his skinny frame barely covered by a chiffon cardigan, there stood the next descendent of Bowie and Morrissey. The latter couldn’t resist covering their Moz-ish B-side My Insatiable One. Always with an eye toward the bitchy he then proclaimed in an interview, ‘Brett Anderson will never forgive God for not making him Angie Bowie.’

After a string of superb singles came the epic Stay Together followed quickly by Dog Man Star, which became one of my favourite albums of the decade. Bernard departed; to be replaced by a teenage fan that followed his, at first, slavish imitation by co-writing hit after hit on Coming Up.

After their split, followed by a well-publicised bout with drug addiction, Brett has, to little attention, moved forward into a surprisingly brilliant musical reinvention. Not that you would know about it, since his albums don’t attract the press these days. Admittedly out of nostalgia I grabbed a ticket for last night’s gig, my ardour having been reawakened by the news of Suede’s forthcoming brief reformation, minus Bernard, who seems busy enough wasting his talent on helping Duffy make average records, for one of March’s Teenage Cancer Trust gigs.

Everyone wanted Suede songs, there were none played. At first there was an understandable restlessness to the crowd, with it being a Friday night and everyone desperate to remember what being young was like. For an artist whose not yet made his name as a solo artist this is a dangerous game. You’re selling tickets on reputation while virtually no one knows any song they’re hearing. And then suddenly, you let go of the reason you came, you forget that you were there to recapture a part of your youth. And the reason this happens is because of the dark, lush, Scott Walker-ish, torch songs coming at you. Cello and piano fill the room and that voice, more powerful than it ever was, sells it. It hardly hinders that the man has charm to spare. Now 42, he’s still dazzling to look at, in a sunken-cheeked Man Who Fell To Earth kind of way, still rake thin and still as impossibly sexy as he was in 1993.

Brett Anderson, the great overlooked icon of Britpop. I’d wondered if I’d be disappointed if nothing old was played. It was a rediscovery.

...