Manchester City 1 Stoke City 0 :: FA Cup Final, 14-5-11

I'm a 3rd generation Man City fan. My late grandfather, Eli Tray, went to the first ever game at Maine Road, in 1923. We won the FA Cup in ’56 but dad never saw it – no TV! My grandfather took my dad, aged 10, to his first match in 1960. Due to having to leave school to help support his family, he got a job in Burton's Menswear in Deansgate, Manchester, in 1965, working 6 days a week, including Saturdays, and almost never got to see the great City teams of the late 60s/early 70s. He'd go to the odd away game but missed the glory years, including our title-winning season of ’68 and our last FA Cup win in '69 against Leicester.

I’ve seen the old footage; the scorer, Neil Young (no, not that one, he didn’t moonlight between CSNY gigs!) fired in a Summerbee cross and won us the cup. Neil, Manchester born, was of the old brand of players – he never earned much money and when his career ended he battled alcoholism and depression, finding work as, variously, a milkman, a supermarket worker, sports shop manager and insurance salesman. Diagnosed with cancer at the end of 2010, the club stepped in to pay his medical bills. He died in February. The cup run was dedicated to him, including a poignant match against ’69 Cup finalists Leicester where the thousands of away City fans held a banner and stood in silence in the 24th minute – the minute he scored the ’69 winner.

We won one more trophy after that, the League Cup in May 1976, 5 months before I was born. After years of missing the games, in 1978, 2 years after I was born, dad stopped working Saturdays and bought a season ticket. He tried to shield me from the misery of being a City fan, and who could blame him? His dad passed in 1979, so I never got to know him or what a proud Blue he was. His season ticket purchase heralded the start of a pathetic decade for the team but I had the bug, I had the genetics, and that was that. In the early 80s I found my first favourite player, Paul Power, now one of our Academy managers. Dad went to the FA Cup semi against Ipswich at Villa Park in ‘81, and watched us win. He went to the final shortly after, standing behind the goal, as Hutchison's own goal took it to a replay. The replay was on a Thursday night, and he couldn’t get the day off work. But he couldn’t bear to miss it either, so, despite having Springsteen tickets for the night of the game, he stayed home while mum went to see Bruce and watched us lose to Spurs. He said he’d stayed in because he didn’t know when our next final might be. He was right – it was 30 years.

Despite the 80s being a shocker of a decade for us, I persevered, my youthful enthusiasm trying to pull him out of City darkness. He tells me that every second Saturday I'd see him at the bottom of the street, coming back unhappy from Maine Road, and I'd run to him; he’d pick me up and I’d say 'don't worry dad, we'll win next week!' I had no idea of the decades of misery that I was, that we were, to endure. In 1988, when I was 11, my grandfather, Cyril Clark (mum's dad), who had been both a United and City fan in the 60s, which was possible then, took me to my first match at Maine Road, a reserve game against Liverpool. His split loyalty went back decades. He’d lost a friend in the Munich crash, a factory (and racecourse) owner who his dad had worked for, and started going to see the blues one week and the reds the next, though his heart lay with City in his final years. I can still remember that day, walking up the steps to be greeted by the huge green expanse of pitch; it felt so special, like I was where I was meant to be. In the early 90s, my dad’s best friend, Martin, a United season ticket holder, took me to their training ground to meet the players, including Hughes, Ince, Giggs, Bruce, Pallister and Schmeichel. He tried to convert me! I did quite enjoy the trip and felt a little confused for a short while (maybe a week!). A couple of years later he took me to Old Trafford and I started to wonder. What if I felt something? What if I loved it? I needn’t have worried. I sat there, feeling like an outsider. I felt nothing. These were not my people.

By the early 80s, grandpa had gotten a season ticket too, so he and dad went together – with a flask of coffee, they braved the terrible quality on show and stuck with the team, as you always do. We were relegated in ’82. In those days, if my grandfather couldn't go, I might even get his ticket. He passed in 1990 and going to the match without him just wasn't the same for my dad. He stuck it out for another 5 years, during which we went many times together, including on my 21st birthday where I was overjoyed to have my name read out by the stadium announcer. But he gave up his season ticket, because of price and because getting those two buses to Moss Side from our house in Crumpsall just got too hard. I'd always said to dad, when City gets to Wembley we'll go together! What did I know? We were never good enough to get there. Then, when he gave up his season ticket, he couldn't bear to tell me that even if we did get there we'd never get tickets because only season ticket holders get them. We were relegated in ’96, then again in ’98, dropping to the 3rd division, a new low. The game that sent both our opponents and us down was, ironically, against Stoke, who we beat to no avail. We lost games to Lincoln and, worst of all, at home to Bury and scraped past teams like Wrexham and Mansfield in little provincial grounds. It was depressing and humbling. I was at Bury College at the time and, I can tell you, that was a long Monday after we lost to Bury. Even at that level, we were getting an average gate of 28,000 at home. The next highest gate was, ironically again, Stoke, with about 10,000. It took them a few years longer than us to get out of that division. This was the same season that was United’s most successful ever – it was tough to watch them win the treble while we toiled in the lower leagues.

After a hard season, we made it into the play-offs. On Sunday May 30th 1999 dad and I watched the game against Gillingham, the 3rd division play off final, in United fan Aron’s house. Despite our differences, the fans of both teams are always connected – at work, at home, at school. Aron cheered and I wept as we clawed our way out of the division, Dickov and Weaver the heroes. Dad leapt dramatically off the sofa when we equalised in the 95th minute and then won on penalties – a game that changed the future of my club forever. The year after that I moved to London. I go to as many London away games as I can and, once a year, on Boxing Day (or the 28th), dad and I attend our annual City home game together when I visit for Xmas.

It's all I've ever wanted – to walk down Wembley Way with my dad. I don't dream of winning the Premier League and I never dream of winning the Champion's League. Just a Wembley cup, that’s my dream. Disappointment is such a familiar feeling to us, it's what I've had my whole life. When we got to the final I knew we’d never get tickets and dad said it was ok, we hadn’t watched any of the cup run together and he didn’t want to jinx it. We get a bit superstitious with football! In the week leading up to the final I didn’t sleep much. How would I deal with losing? Up to that point I’d just been happy, thrilled actually, to even be in the final but now the game was a few days away I wanted to win it. It could have been worse, we could have been playing Chelsea, but our record against Stoke was really poor. By 2pm dad and I had been on the phone half a dozen times, winding each other up in nervousness. It's the build up that kills me, I just wanted it to start. Matt arrived just in time to calm me down before the game started and we settled in to watch it upstairs – couldn’t watch it in the living room, since I’d watched the semi in my room. No tempting fate for me. Having him there actually chilled me out; I was a bit frenzied but didn’t want to appear like a total nutter so dialled it down a bit. No calling dad during the match, that’s our deal, unless we’re losing.

Amazingly, we were playing really well. Couple of great saves from their keeper. But I’ve been there before. Seen us play well and lose, more times than I can count. Half time, glasses of whisky, the cigarettes started piling up in the ashtray. We talked about football, work, a gig I’d seen the night before, the Olympics, and a hundred other subjects and it was just what I needed. Second half and the same pattern, one chance for Stoke; Hart did his job and closed the striker down. Nerves were rising again, and then in the 74th minute a neat little move – Tevez to de Jong to Silva to Balotelli, a neat back heel, a blocked shot and then… the semi-final hero, Yaya Toure, appeared and smashed the ball into the net in a flash. No stopping that. We exploded! The fans were going mental; I was punching the air, and that most pure feeling, the scoring of a goal, knocked me down. What feels better than that? But of course that meant 15 minutes of nail biting and, I tell you, those 15 minutes felt like years. The slowest ticking clock of all time. Three minutes of injury time. Please please please, let me get what I want, this time.

Whistle. All over. The room started spinning. Tears came to my eyes. We hugged, we shouted, the screen was a blur of blue happiness, crying fans. There were little kids who’ll never know what it was like to want and need and desire and beg for years on end. There were teenagers who joined up hoping for more than their dads had received. Their mums and dads, my age, wept after 30 years of getting nothing in return for their devotion. The guys in their 40s who just about remembered the ‘81 Cup Final couldn’t believe how long ago it felt. The fans my dad’s age – priced out of their season tickets 15/20 years ago – this was for them. We had to sit and watch while United won a dazzling array of trophies, while our team descended in relegation after relegation. The older fans who remembered the good times; the ones my age who’ve never known them; the kids for whom this will cement their love of the blues forever. I called dad, both of us in tears; I had to give Matt the phone because I couldn’t talk.

My team. My shitty team went and won something. The first trophy is the best. Who knows if there’ll be more, but these players and this manager have changed the club’s history forever.

Sufjan Stevens :: Royal Festival Hall, London, 13-5-11

Image © I-boy, the arts desk

I’ve been avoiding writing this. Because, what I saw on Friday night, which I might call a psychedelic happening of sorts, consumed me to the point of disorientation, joy, worship and downright awe. There are gigs and then there are shows. Experiences. Events where you walk out of the auditorium so dazzled that you struggle to comprehend and describe what you’ve witnessed. Sufjan Stevens.

He’s come a long way from his early folk days, making albums like the scripture-influenced Seven Swans, progressing to more ambitious projects like Illinoise, part of his, now abandoned, vow to make an album about each of the 50 states. Michigan, Illinois, what was next? Rhode Island?! Perhaps it was a gimmick, perhaps he believed it but, regardless, I’m grateful that, following the release of the wonderful All Delighted People (his idea of an EP – an hour long) in August 2010, he launched The Age of Adz, one of my albums of last year, in October. A song cycle of epic beats, samples and fluent guitar and keyboard playing, anthems all, it spoke of his inner spiritual crisis and, without putting it lightly, recent mental breakdown. It’s an extraordinary piece of work.

To perform it, he didn’t just roll out the songs and collect the applause. He spoke of star people and celestial visitors, all dripping with his unique blend of goofy, adorable, innocent irony. He knows how pretentious it all sounds, and seems to have a natural tendency to preface his banter with winks about bullshit psychobabble. London audiences aren’t much for rambling so you can imagine that we knew we were witnessing something unusual when you could have heard a pin drop during his ten minute tale of self-labelled Louisiana prophet Royal Robertson, an artist who created apocalyptic sci-fi comics and canvases, turned his home into a study in eschatology and stayed in touch with his inner id by refusing to take his schizophrenia medication. Sufjan clearly sees him as a kindred spirit, another casualty of spiritual panic, struggling to reconcile himself between his Christian faith and the pull of the universe. Both men design to hold onto their sanity in the middle of the wonder that surrounds us in the face of overwhelming outside influences.

His ten-piece band, dressed in fluorescent suits, played his complex art-rock electronica, with a screen behind them and, often, in front; a gauze descending to the floor as geometric shapes and spaceships whirled on both screens. Throwing off his feathery angel wings after the first song he indulged in some seriously daft dancing, and this was the mix of the night – cult of personality, intricate, powerful music, a product of 21st century technology and true vision, and a self-deprecating tale here and there. There’s an awareness of his genius within him, which is belied by his fantastically uncool charm. He almost seems embarrassed to be putting this deeply personal, but attention seeking, heartfelt, but self-indulgent, material out there.

Late on, he put on a silver cloak, with a rotating mirror ball chest piece, as a giant diamond prop descended from the rafters. It looked even more amazing and odd than it sounds. Sufjan is endlessly inventive and creative, with a delicate voice, and undeniable proficiency on any instrument he chooses to pick up; I can say after more than 20 years of gig going I’ve never seen a performance quite like it. The main show came to an end with a nearly 25 minute rendition of Impossible Soul, from, like most of the evening’s material, The Age of Adz. We sang its blissful refrain – boy, we can do much more together, it’s not so impossible. The encore saw a couple of Illinoise tracks, accompanied by Flaming Lips-style balloons and confetti tumbling from the ceiling, as the hall’s seats were abandoned and we danced joyously, led by this Pied Piper.

“Hi, my name is Sufjan Stevens and I'm your entertainment for the evening. We're gonna sing some songs about love, death and the apocalypse. It should be a lot of fun”.

Seven Swans

Too Much

Age of Adz

Heirloom

I Walked

Now That I'm Older

Get Real Get Right

Vesuvius

Enchanting Ghost

I Want To Be Well

Futile Devices

Impossible Soul

Encore:

Concerning the UFO Sighting Near Highland, Illinois

Casimir Pulaski Day

Chicago

Pharoah Sanders :: Ronnie Scott’s, London, 4-5-11

If you’re a pop musician you’ll never be cooler than when you were under 30. Indeed, the Beatles split before any of them reached that age. At the pinnacle of being respected and lauded, you’re told you produced your best work and you have a, say, 10 year purple patch before everyone starts saying you have nothing left to offer. And on comes the next bright young thing. With some notable exceptions, Radiohead spring to mind, being over 35 in pop music is a tale of raging against the dying light. Your audience gets old with you, you don’t attract fans who were your age when you started, your new albums are wheeled out to flog tickets for your tour, the only way you can make money now, and if you’re very lucky you won’t lose your jawline to chins, your waistline to elasticated trousers and your hairline to suspiciously placed hats.

You’re Van Morrison, Stevie Wonder, or Tom Jones; you haven’t made a decent record since the 70s even though your live shows are still worth going to, for nostalgia purposes only. You’re the Stones; you drag your excess skin out on the road for £125 a ticket. You’re Iggy Pop; with your ass hanging out, you look incredible and you do deliver live but it’s a schtick now, though it is remarkable that you’re alive at all. You’re Bowie; you’ve retired because after 5 decades of genius and, frankly, getting more beautiful with age, like Elvis should have but never did, you look a bit old now and you're too vain, and uninspired musically, to flog your hits anymore. Good for you. Better to give it up than be out there and phone it in. Then again, you might be Robert Plant; you don’t give a shit because everyone told you your career was over at 30 and you clawed your way back, using your voice in new ways, collaborating with peers and, lost looks aside (with the exception of resplendent hair) you get respect anew in your 60s. In popular music this is the dance, this is what you go through. And that’s if you’re already famous, your records are already owned and your gig tickets already sell, never mind if you’re trying to be heard in a sea of pathetic self-promotion and endless self-publishing.

However, there are genres, invisible to most, that don’t panic about their lack of attention, finance, talent shows, and all the other accoutrements that popular music is so desperate for. Metal is one, classical another, but, for the purposes of this, let’s talk jazz. You’ve heard it all before, that the musicians on stage have a better time than anyone listening, to paraphrase Tony Wilson. Marmite music. I think in order to appreciate jazz you do need to have an interest in musicianship, because, for wont of a better phrase, there is a certain amount of showing off involved. In terms of attending a jazz concert in the current era, where the great –tets of the past (Miles’ quintets, Monk’s quartet etc) are long gone, only a few of members of each generation remain so you get a fairly elderly figurehead taking on a group of session musos and doing what they know, what they’ve been doing for decades: getting out on the road in a different dark bar each night. But instead of what happens when old rockers go out on the road - at best, raking it in by filling a soulless arena with mums and dads revisiting their youth, or, at worst, eliciting groans from the critics bemoaning your tepid delivery while anyone in the first 15 rows winces at the state of your face - you’re faced by vibrant, thrilling sonic experiences delivered by men for whom age means they’re at the top of their game, not the bottom or, worse, the middle. Since improvisation is key, it doesn’t matter that the song might start out in the 50s, because it certainly comes round to the very moment in time that your ears take it in. Not that there’s no decent modern jazz being created, released and played, there certainly is, but that’s a whole other article.

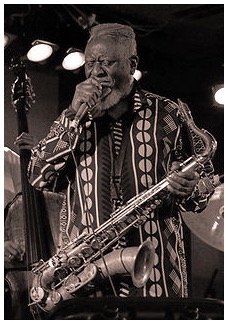

For once, you feel, the musicians are truly being respected. In rock, if you’re out there playing as a session muso for some dinosaur you’re happy to have the pay check, because you certainly aren't going to get the respect, perhaps because you’re often playing material that’s unchallenging. In jazz, playing with a remaining great, like Pharoah Sanders, is the pinnacle of your career. At 70, he’s playing more powerfully, with more skill and intricacy than he did in the 60s – when he was Coltrane’s favourite saxophonist. That’s some compliment. Described by Ornette Coleman as the best tenor player in the world, his lengthy, dissonant solos graced half a dozen Coltrane albums. In 1969 he released his masterpiece, the 30-minute free jazz blowout, The Creator Has a Masterplan. McCoy Tyner, Don Cherry, Sun Ra and more have all sought his playing in a career lasting 50 years.

I found it impossible to resist rushing to see him at Ronnie Scott’s recently. While the show was far from my first jazz gig, to my shame it was my first at Ronnie Scott’s. And what a venue, reminiscent of New York’s Village Vanguard; I had a little chuckle as I sat in the plush surroundings, surrounded by photos of jazz luminaries on the walls, low lighting, red table lamps, high-end fixtures and fittings and table service. You don’t get treated like this at a rock show. This was a long way from sticky floors and sweaty, beer-sodden gig-goers. I particularly enjoyed the body language of the table of couples in front of us – who had quite clearly picked Ronnie Scott’s on a random night, probably thinking they’d get some easy listening jazz to go with their bottles of white wine and birthday celebrations. The look on their faces as Sanders blew with wild abandon was a joy to behold. How wonderful that jazz can still horrify the tender-eared and inexperienced. It was an example of regular folks thinking they know what jazz is all about, then being shocked into silence by it. They should probably avoid Cecil Taylor.

What an honour, what a privilege to be in the presence of Pharoah Sanders. Accompanied by dazzling musicians – double bassist Mark Hodgson; pianist Jonathan Gee and drummer Gene Calderazzo – it was truly the most transcendent jazz concert I’ve witnessed. And this cool, charming pensioner blew everyone’s ears off, playing better at 70 than he did at 30. How refreshing to see a genre that doesn’t worship the young, but instead lauds achievement, and allows its members to actually get better with age. The very structure of jazz is designed to allow the artist to create something new with something old, and its demands are the opposite of rock music – slavish note-for-note recreations of hits are unacceptable. In an era of instant success, selling out arenas on one album, this show was a testament to well-earned longevity and timeless class.

...