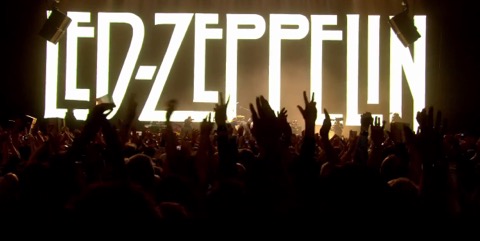

Led Zeppelin :: Celebration Day

Led Zeppelin never did get a proper send-off. I suppose there’s Knebworth ’79 , with a bloated, but still brilliant, John Bonham behind the kit. That was his last stand, certainly. But by then Plant had grown up, discovered irony and started to parody his own Golden God ridiculousness. Knebworth was good. It wasn’t great. Let’s not even go there with Live Aid (Phil Collins was the drummer). Then, to honour their mentor Ahmet Ertegun, who had signed them to Atlantic after hearing one demo, they did reasonably well, with Bonzo’s son Jason on drums, at the Atlantic Records 40th anniversary do in 1988. A couple years later they all jammed at Jason’s wedding. Seriously. And that was that. Until Ertegun passed away and, for his charity foundation, they agreed to do one big show at the O2 in 2007.

It’s been felt that Plant is the one who has moved on most successfully, professionally and personally. He’s a clever and engaging man, a blues scholar, a country bluegrass singer, a wonderful interpreter of song , and a hundred other things including a very private fella (so would you be if you’d had kids with two sisters in different decades). But this show, this one night, was his last chance to just drop it all and say ok, I give in, I’ll shake my mane and tilt my hip and play the part all over again. Everyone who attended went crazy about how good it was and then that was that – a DVD was expected but never arrived. Everyone knew it was recorded so what was the problem? Well, anything that has the Zeppelin name has to be perfect, and every fan knows that. It’s why their Live Aid show was kept off the box set. It’s why Plant refused to let half of his performance at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert go onto the DVD. That’s how they are. So what a shock when, a month ago, it was announced that, five years after the O2 show, it was coming out on DVD and in the cinema. Cue fan frenzy. I had to go and see it on the big screen. I’ve just returned and I’m waffling because I don’t know how to begin to describe this overwhelming, extraordinary musical experience I’ve just witnessed. I should say that I had a bootleg CD of the show the day after and a bootleg DVD the week after so I knew the content. But seeing it properly fixed up, on the big screen: it just knocked the wind out of me.

Right from the start – Good Times, Bad Times, track 1 from their 1969 debut album – the band crowd round the drum riser, and they barely move from that central square throughout. They’re connected, in a way that very few musicians are, and every nuance, every note, every smile, every single aspect of the performance is utterly, completely, inevitably and beautifully perfect. Every band member is on his own personal journey. If Bonzo himself were alive there’s not a chance he’d have been as good as Jason was that night. His powerful, muscular, frenzied energy powers the entire concert; he’s the rock on which everything builds from, and it’s clear how much everyone else relies on him to provide that explosive foundation, as strong as the one his dad built those 40 years ago. Listen to The Song Remains the Same and tell me that he doesn’t outdo his old man with ease. Listen to Kashmir and try not to feel your spine bending with those thunderous bass drum kicks. And listen to that final flourish in Rock and Roll and you’ll know in that moment that not a drummer on earth could have done it better.

John Paul Jones, then aged 61, has carved out a rather fascinating career as a collaborator, with the likes of Diamanda Galas and Brian Eno, and as a producer/arranger, most notably creating the gorgeous string parts on R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People. After this show he found his taste for playing live again with Them Crooked Vultures but at this performance he’s a serene, anchoring presence, though I could have stood to hear his bass a little more crisply in the mix. He comes into his own on keyboards and organ on a flawless No Quarter, fluidly nails the lovely melody line on Ramble On, leads the show during Trampled Underfoot, and what a pleasure to hear that bass run on the big finish at the end of Dazed and Confused. He and Page have an almost telepathic connection, two old stagers butting heads and grinning at each other when they know they've hit a perfect moment, when everything has gone just right.

Jimmy Page, then aged 63, is looking a little haggard these days, but so would you if you’d lived the life he’s had. There’s a reason that kind of guitar playing died out – surely looking at those scrunched up faces just got too funny after a while. In a way he has the hardest job of all, because he’s not played these songs, or indeed any songs, on stage regularly since the band broke up. He turned up for Plant’s 1990 Knebworth Festival encore , and reunited with him for a quite brilliant 1994 TV special for VH1, followed by two well received tours together in 1995 and 1998. But on the whole you know he’s the one who’d most love to be that guy again. The one who is the least creatively satisfied with what he’s accomplished in the last few decades. (Whisper Coverdale/Page if you dare.) He just wants Plant to be his guy again. And there’s no way he can play like he did when he was 25, just as Plant can’t possibly sing like he did when he was 25. But with all that said, he delivered one of the performances of his life. Not every note was perfect, not every run was as fast as it used to be, but he put every single shred of himself into that performance – from riffs to solos to violin bows to a bit of Theremin, it was all there. And he got better and better with each passing song, as if he was finding inside himself some internal clock that he was able to force backwards.

Oh Planty, Percy Plant, the former layer of tarmac on the road to West Bromwich. The Golden God (age at gig time: 59). The man who survived the 80s, somehow, to go on and win the Grammy for Album of the Year . The man who launched a thousand utterly terrible copyists. The man who shook his luscious blond hair, wore the tightest pants in rock, stuck his bare chest out, and howled like the hammer of the Gods was upon him. He has so very much to answer for. It all rests on him, truly. The band played like demons and shook the foundations of the venue, the cinema and my aching, bruised head (I fell off a spaceship the day before, but that’s another story). The groove these guys got going behind him was out of this world – no pressure then. But which Plant would turn up? The one who’s barely bothered to look back to those days, to his credit? Could he just shove it all aside and play that role for one night only, for the last time ever, and not ruin it by winking or getting the tone wrong? He had to be the last hold-out, the last person who wanted to do this, but he was doing it for Ahmet, not for himself. So he just stepped out onto the stage and, like an actor playing a classic role in his twilight years, he howled and preened and nailed the shit out of the songs. He took it seriously, finally. Not the songs themselves, after all, half of them are about rescuing maidens from castles or climbing mountains dressed like Gandalf, but the music. The sound, he just used the noise itself to push his performance to the limit. And, like Page, he just got better song by song and, being as smart as he is, he knew what to hit and what to leave. He knew which songs to excise (no Communication Breakdown or Rain Song; too high, they’d sound wrong sung lower) and he knew which moments to let go. He’s no fool: there were notes he’s a mile away from being able to hit so he used his voice, as he has been doing for the last 20 years, very cleverly and gained power and confidence with each passing minute. He’s still snake of hip (if not of jowl) and manages to exude sex almost every minute he’s on stage. And blow me down, he truly looks like he’s enjoying the night, getting off on every second and the camera captures some wonderful moments of exchanged ‘we’re really doing this!’ recognition and affection between him and Page.

They turn to Jason often, and these precise, insanely powerful songs just come at you in waves. It’s actually highly moving, seeing these four people on stage side-by-side. And that’s why they should never do it again – because it was so perfect. I hear people say that there are no bands like Zeppelin around any more. And perhaps it’s good that the more bloated bands of that ilk are long gone. But I tell you what – there were no bands around like Zeppelin even when they were around. No-one could touch them. They were out there on their own for so many years. And that’s not bad considering that I can’t tell you what a single song lyric is about. It’s the sound, it’s the interplay, it’s the alchemy – man for man, Zeppelin are the best rock band there’s ever been. And that holds true in 1969 and in 2007. I used to say that, if I had a DeLorean, and I could go back in time for certain gigs, I’d choose a particular bunch, like Bowie at the Hammersmith Odeon ’73, Hendrix at Monterey ’67, and a dozen more. And then I would always add to that list, Zeppelin at Madison Square Garden July ’73, aka The Song Remains the Same concert film. But now, today, right this minute, I’m taking it back. That night, December 10th 2007, is the one I’d choose as the crowning night of their career and the one I’d have given anything to attend.

Jack White :: the Roundhouse, London, 8-9-12

Jack White repackages the blues (and a bit of country, bluegrass and folk) in his own dirty, stripped down way, to an audience who probably knows little about its history or leading figures. This can only be a good thing. He’s an old fashioned sort; there’s no frills (or self-indulgence) to his music but, undoubtedly, stagecraft is his speciality. Watching him at such close quarters was a joy: he expressed himself with power and passion, he shredded to within an inch of his life and his excellent band, or bands, back him with the kind of belief and musicianship he’s never been surrounded by before. I say bands, because yes, there are two.

First up were his all-male band, The Buzzards – keyboardist (and Mars Volta member) Ikey Owens, the brilliant Daru Jones on drums, bassist (often on double bass) Dominic Davis, violinist/pedal steel player Cory Younts and Fats Kaplin on second guitarist/fiddle/mandolin. His music has always been rather masculine and virile, and yet, the show only truly kicked off when his first band made their exit mid-song to be seamlessly replaced by his all-female rhythm section, The Peacocks. Punching even harder than their male counterparts, these women laid waste to the songs. Much has been said about his attitudes toward women but only a fool would deny that he is quite clearly musically smitten with each and every member of this band. They all dazzled: the awesome Autolux drummer Carla Azar , pianist Brooke Waggoner , co-vocalist Ruby Amanfu , fiddler player Lillie Mae Rische , Margaret Bjorklund on pedal steel and bassist (formerly a Cardinal for Ryan Adams) Catherine Popper .

Still, this was a free concert to promote iTunes, so no music was on sale. I guess running those two bands needs the odd concession. He ran through his own greatest hits – a dozen White Stripes songs, three from his Raconteurs period, a couple of Dead Weather tracks and half a dozen from his excellent solo album Blunderbuss. This whole show was just plain fun. The interplay was next level, and at times he seemed completely taken over, possessed, ferociously channelling this music, as the electric currents passed through him. What a privilege to watch this extraordinary performer, singer, songwriter and guitarist at such close quarters. These are just brilliant songs: Black Math, Hello Operator, Hotel Yorba, Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground, Ball and Biscuit (with a nice snippet of Dylan’s Meet Me In The Morning at the start) and of course, to finish, the frankly iconic Seven Nation Army.

I still have it in me, it turns out, to take on the pit at the front of a gig. But I couldn’t match this southern gentleman for energy, intensity and conviction. I walked out aching, and he’s doing it all again night after night. Of course, the old tropes were there – gently berating the audience for not making enough noise, having his manager (I assume, like his entire crew he was kitted out in a sharp suit so he could have been a roadie) good-naturedly exhort the crowd to leave their mobiles in their pockets and just enjoy the show and so on. It was old school but never felt contrived. It felt primal, distorted, thrilling and, paradoxically, completely current. I love a back of the venue saunter but, truly, you can’t beat looking the performer in the eye. I must do it again.

http://www.setlist.fm/setlist/jack-white/2012/roundhouse-london-england-33ddbc61.html

http://jackwhiteiii.com/news/

Elizabeth Fraser :: Meltdown, Royal Festival Hall, London 7-8-12

As she stood, very still, the crowd collectively inhaled. The backdrop, a sprawling, black, metallic silhouetted tree over a latticed screen, which covered much of the back of the stage, started to come to life, and projections started to run. The ambient noise from her side-stage tech guy that had wound its way around every quiet moment, and would continue to between songs throughout, stopped and her band started to play. A visual focal point was her keyboard player – a cross between Mike Garson and Ming the Merciless, and with the fashion sense of Klaus Nomi – who commanded a bank of vintage organs and synthesisers. The guitarist made Torn/Fripp sounds, excellently; the drummer, in his glass box, surrounded everything with consummately played fills. The bassist switched effortlessly from bass to rhythm guitar. However, the sound, one must say, was poor at times. A shuddering bass seeped out of the speakers now and then, overwhelming all. The two female backing singers were sometimes superfluous. The sound mix was, at times, annoyingly poor. Everything was designed to frame her voice, but since it’s not the loudest there is, the mix was an engineer’s struggle. But despite these flaws, the voice everyone longed to hear was to win. Imperceptible at first, this delicate, undulating sound started to come out of the speakers. Like a hummingbird, it buzzed up and down and around, barely noticeable. It’s not a strident voice, and it’s not going to make the chairs wobble and the glass crack, like Diamanda Galas did last week. But it soars and swoops and, quite honestly, is one of the most beautiful sounds that has ever passed through my ears.

The love washed over the stage in waves. As each song ended, applause and feting filled the room. Declarations of love and marriage were suggested. She smiled sweetly. Just less than half of the set was new material – it reminded me a little of the more recent Kate Bush albums (now there’s a Meltdown fantasy: Kate curates) – and the remainder was old Cocteau Twins songs, greeted like long lost friends. I don’t think a single person present thought they were going to hear these dream pop masterpieces ever performed again. In all seriousness, while she’s been away, her band’s music has had an immeasurable influence. A band like Beach House (or Animal Collective or Bat For Lashes or the xx, and so on) simply wouldn’t exist. The esteemed indie-folk-pop record label Bella Union wouldn’t either: started by former Cocteau’s Simon Raymonde and Robin Guthrie, the label has given us the aforementioned Beach House, Explosions in the Sky, Fleet Foxes, John Grant, The Low Anthem, Midlake and dozens more.

That her voice is unintelligible, in terms of lyrics, matters not. It’s all about the sound. At times I felt as if I was in a waking dream, with the perfect soundtrack. Her instrument is untouched by years of touring, of slogging around the world and its festivals, and this concert was enriched for it. It’s slightly different, of course, with age, but the mesmerised audience was rapt and thrilled. She must have no doubt now of how much she is loved. In truth, she looked deeply touched at the standing ovations, applause and bouquets offered, and taken, from delirious fans. As she encored with Song to the Siren, a strange and exquisite Tim Buckley song, which, Teardrop aside, she is best known for (recorded as part of This Mortal Coil ), I thought I might dissolve into the seat. Simply, it was the most beautiful rendition imaginable of one of the most beautiful songs ever written. Gratitude fills me – to Antony for the invite, and to Elizabeth Fraser for overcoming her fears and saying yes.

...

Diamanda Galas :: Meltdown, Royal Festival Hall, London, 1-8-12

Avant-garde

Noun:

The advance group in any field, especially in the visual, literary, or musical arts, whose works are characterised chiefly by unorthodox and experimental methods.

Adjective:

Of or pertaining to the experimental treatment of artistic, musical or literary material; belonging to the avant-garde: an avant-garde composer; unorthodox or daring; radical.

What has the over-used term avant-garde come to mean? Anything that’s even a millimetre outside of the perceived mainstream; perhaps a Whistle Test prog throwback glaring blankly at their audience through their beards while new instrumental shoegaze swirls around an East London club with a dreadful sound system; or a hipster Brooklyn electronic ‘collective’ declaring their album works best with 12 concurrent mixes. Ok, I’m guilty in this regard: from Okkervil River to Dirty Projectors to the Flaming Lips, count me in. But I know, truly, that calling something ‘experimental’ is a lazy term used entirely too often to describe anything that’s even a little sonically different or visually intriguing, and it’s mostly used inaccurately to label music that isn’t daring or radical at all… and then, among all that wankery, with thanks to Antony Hegarty’s first Meltdown night, I found the real thing.

The audience are always a fascinating barometer of the artist. I keenly observed the Guardian-reading South Bank crowd + a few specs-wearing, plaid-clad hipsters + a hell of a lot of alternatives (a Torture Garden kinda crowd: all tattoos, flesh tunnels and those who graced the 90s as goths). My gig companion had seen Ms Galas at a Brel tribute in the same venue, singing Amsterdam, alongside Marc Almond and other kind-on-the-ear artists: she was booed. I asked why, but he found it hard to explain, exactly.

Within a minute of her striding to the piano, I knew why. Out came this… noise. Operatic and dramatic, enveloped by dark, rolling piano trills, this instrument, this vocal, guttural sound, coming from some unholy place, filled the auditorium. My earholes were being assaulted. I had no idea what this insane woman was screaming about but I knew it was in Italian. The next song was in Greek, then Italian again, then Spanish, then German, then French, one in English, back to German, Italian and so on. Every song was about death. It was unbelievable, truly. You just never knew what was coming next – more ear-splitting soprano shrieking? A chanson-style growl at least two octaves lower? A middle eight which consisted of only high-pitched, but completely controlled, banshee wailing? Yoko’s got nothing on Diamanda. It was sometimes unlistenable, yet often deeply moving, and you wanted it to be over but you never wanted it to end. The most traditionally enjoyable song was a little bluesy, but still ended with a truckload of piano banging.

Near the end I played out several fantasies in my head: Diamanda on the X Factor, the look on Cowell’s face; Diamanda invading a hen-night-jukebox-musical, like Dirty Dancing, and the theatre staff locking the doors; Diamanda on a Lloyd Webber Saturday night BBC1 West End competition show – perhaps she could be the next Wicked Witch? Diamanda on the Royal Variety Show: following Brucie, bowing to the Queen, perhaps a duet with Gary Barlow?

I’ve been watching live music for 24 of my 35 years. I have never seen a gig like this. It was like being punched in the face with sound. Half way through the show an audience member dared to express her devotion with a plain ‘I love you!’ The Cruella De Vil-esque response: “Do you know who you’re talking to? Shut up!”

At the end of the show, as my entire being tried to recover from this unique experience, Antony quietly made his way on stage to hand her a bouquet of flowers. A symbol of traditional beauty, grace and elegance, she accepted it with an affectionate, benevolent smile, took her bow and her standing ovation and walked slowly into the wings.

...

Manchester City – Champions of England :: 15-5-12

By anyone’s standards, the last few days have been groundbreaking and historic. Where to start? I see I haven’t written anything in this blog for a year, I can’t say why really, perhaps I’ve just not been feeling the writing since last summer. Anyway, doesn’t matter: this one is certainly full of incident. So, it’s a football blog, but it’s really more about family, as football always is. It’s about my dad, my team, civic pride, community, togetherness, and feeling connected to total strangers. Best of all, it has a happy ending.

How many years have I had to take shit from Manchester United fans? It started when I was a kid, one of three City fans in the school. At least it seemed that way, there may have been a few more, but they wanted to avoid being mocked so they probably kept quiet. This was in the late 80s through to the late 90s, a period where the reds had started to win every trophy going and the blues were hiding in the corner, with a collection of comical mishaps in our recent past – awful players, inept management and increasingly bitter fans. The United and City paths had been similar, pretty much, and then started to diverge wildly in 1990 when United won the FA Cup, then bagged a European title in 1991, and then in 1993 collected their first Premier League trophy for 26 years.

And the years came and went and City got worse and United got better (and spent plenty of cash on players incidentally, throughout) and the jokes became more painful and the relegations started. The phrases ‘Typical City’ and ‘Cityitis’ were invented, to describe our state, which you had to laugh at, otherwise you’d cry. We were a laughing stock, a once-great club reduced to rubble, patronised and ridiculed in our own town. On the rare occasions where we’d play United we’d take our beating in good humour and go slinking back to our corners. This was my life: my youth, my school years, my teens and my twenties. The final indignity came in 1998, when we were relegated to League One (the third tier of English football) and scrambled for points at teams with tiny followings, who welcomed us with glee to their grounds like it was their cup final. Humiliations aplenty followed, which included a defeat to local club Bury, who got the result of their lives by beating us 1-0 at Maine Road. As a student at Bury College, at the time, I don’t have the words to describe how painful that Monday morning was.

But we fought, and with an inspirational captain and leader, Andy Morrison, whose book I later edited, we ground out results and got to the play-off final, where I witnessed the single greatest football moment of my life in my friend Aron’s living room. Aron, a rabid United fan, cheered right along with dad and I, never thinking I’m sure that this lowly team would ever rise up to challenge his. A few days earlier United had won the treble of course (Premier League, FA Cup, Champion’s League) and held a victory parade through the city centre, where they flaunted their hard-won trophies. City were too embarrassed, understandably, to make much of a fuss about winning the third tier play-off final and shuffled off to toil some more. I remember thinking: what would it be like to go to such a parade? To be so proud of your team, instead of having them disappoint you all the time?

Our League One support had remained strong, with average crowds of 28,000 in that season, but we all knew how important Dickov’s goal was – it changed the future of the club forever. We got promoted again the year after into the Premiership, and then relegated again the season after that. I resigned myself to forever loving, unendingly, with passion and heart, a team who might escape relegation, or even become Premiership mid-table, at best. After the Commonwealth Games in 2002 was over we leased the newly built stadium in East Manchester and made our move. At first, the place was cold and empty, and even now suffers from atmosphere issues, as all big new open stadia do. It had no history. But what were we mourning? We hadn’t created anything at Maine Road worth remembering since the 70s. We bounced up and down between Premiership and Championship (second tier) and then finally attained some kind of stability, thanks to a shrewd businessman, and lifelong City fan (and now FA Chairman), David Bernstein. We got so desperate we let a former Thai prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, who was a criminal, take control of the club in 2007. He spent a few quid, and we did ok with Eriksson as manager, but it was always doomed to fail. And then, somehow, in what might be called the greatest bit of tourism PR in history, an oil-rich sheikh went and bought the club in September 2008. This fella, Sheikh Mansour of Abu Dhabi, a member of the royal family, just suddenly decided he wanted to put his country on the global map, having seen Dubai start to dominate as the Middle East destination of choice. Apparently, he fancied Everton but lost interest as soon as he saw their stadium. But ours, yes, he liked it. So, we became a billionaire’s toy.

And believe me, no-one gave a shit about the money, the issue of so-called ‘selling out’ – partly because we were desperate, and partly because the owner was a crook and we wanted rid of him. It became clear very quickly that Mansour was a very different person from Chelsea’s Roman Abramovich, the previous big-bucks club owner, who had spent half a billion on Chelsea. The sheikh lived in Abu Dhabi, didn't move to England, didn't interfere in transfers, didn’t tell anyone how to run the team (Abramovich, it should be noted, does all of these things and more) and in fact didn’t even come to games (though we’re told he watches every minute of every match). Instead, he gave the Thai villain’s managerial choice, Mark Hughes, a chance and installed a very smart, Boston-educated businessman called Khaldoon al Mubarak to be the chairman and run things. Hughes wasn’t up to the job, we all knew, and sure enough he made a right mess of things, spent wisely on only half of his targets, and was replaced (in a badly handled transition) by Italian Roberto Mancini, a ruthless but fair tactician who, following a glittering career as a striker, had built teams at Fiorentina and Lazio before assembling Inter Milan’s side, which went on to win three scudettos in succession. Mancini is, one might say, a control freak: he does it his way or out you go. With his players - he’s not their mate, like Keegan was; he’s not there to kiss their arses or hug them if they’re feeling down; he’s there to win, and if you don’t like it you can leave. Or, if a player behaves badly and apologises, he’ll wait for them and then wipe the slate clean. Hard but fair, always. In his first full season we won the FA Cup. I never thought I’d be so happy again, and then came Sunday May 13th 2012.

We’ve been the best team in England this season, and we’ve scored more and let in less than our nearest rivals, who just happen to be our lifelong bullies Manchester United. We’ve spent money wisely, we’ve weathered storms of all types (including player misbehaviour, to put it kindly) and we came back when it looked like we’d bottled it in March. After the Arsenal defeat on April 8th, at which time we found ourselves eight points behind United, all I heard was how they’ve been here before, they’ve got the experience coming into the final month, and that they’d see us off just like they had everyone else. Well, not this time. While they are still a very very good team they are not the force they once were. They saw the whites of our eyes, coming up fast behind them and, like their fans, they didn’t know how to handle it. So, they panicked while we won six in a row. We won't be brushed off so easily now. We spent money fast and improved faster and they aren’t going to have everything go their own way any more.

We started to eat away at those eight points. And again, I heard about their manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, being the master of the mind games, letting no other manager best him. And then he went up against Roberto, he cracked up on the touchline at some perceived slight and got up in his face at the home derby and, instead of backing away, as all managers do when confronted with the red-faced grandfather of them all, the greatest club manager of all time, our fiery Italian manager went toe-to-toe, snapping back at him. It was a watershed moment – you will not push us around anymore. You will not bully us. Everything will not go your way. We are not your inferiors, your rivals to be patronised, no longer. We won the derby and our celebrations were muted – we did a job we had to do, we have more in our sights now than just beating United. By then, United had already crumbled to a defeat at fighting Wigan (which I predicted) and slipped to a crazy home draw with Everton after leading by two goals, twice (which I had not). After a sleepless night I watched us play like champions away at Newcastle last weekend, the goals scored by the colossus that is Yaya Touré, who had also scored the winning goals in the FA Cup semi and final last year.

And so, to the final game of the season: home to QPR, managed by Mark Hughes, the man shifted out. He held grudges, it was said, he wanted revenge, which he denied, and he was an ex-United legend. It was all set up for Cityitis, for Typical City to screw it up. We very nearly did. We should have won the title a month ago, but we choked, and then United choked, and now it was all down to this one game. We couldn't win it 5-0, that’s not how we do things. We must drain out the last drop of nerve-shredding stress from every fan that has waited 44 years for this moment. In 1968, the last time we won the league, my dad was 17, and he missed the winning game because he was working and had to read about it in the Football Pink (a Manchester Evening News supplement printed one hour after the match ended). He’s now, he won't mind me saying, 61. When I was a kid, I would run down the street to greet him as he returned from every miserable home match. One year I said, ‘dad, will you shave your beard off if City win the title?’ I’d never seen him without a beard, which he grew after his father died in 1979. He laughed and said yes – I promise you; it was a safe bet back then. He said to me yesterday that he’d said yes because at that time there was more chance of him becoming Pope than us winning the title.

Both he and I had been more than nervous before the QPR match – for a week, I’d barely slept. We were both totally out of our minds. We had put so much into this. Just one win against struggling QPR was all we needed. We had the same points as United and they’d need to win by 10 goals if we both won. Considering how much better we’ve been than everyone, United included, this season, I wasn’t thrilled about it going to goal difference but never mind that, I was ready to take it. It’s said that City fans are obsessed with United. This is true. I guess it’s to be expected if you share your lives, your workplaces and your schools with them every day. I’ve been outside of that for 12 years now, having left Manchester in 2000, and I care far less about United than most blues do. It’ll always be that way back home, I suppose, since we share the city. But now they’re wondering if they’re looking at a coming era where they’ll soon feel how we’ve felt for the last 20 years.

The match was tense, and we had all the play but couldn’t break through. Yaya Touré’s last act of the season, before leaving the pitch at half time with an injury, was to set up Pablo Zabaleta for the opening goal. I was cautiously happy but I feared what was to come, without our midfield lynchpin. The second half began and the fans roared but the Cityitis tension grew, and then QPR scored twice. Doom enveloped us all, overwhelming crushing darkness. For 25 soul-flattening minutes we all just stood/sat where we had watched/listened to the matches all season, gaping in horror: the fans in the ground, dad on the bed listening to the radio (where he can see the stadium from the bedroom window) and me watching the match illegally on my laptop. We were going to screw this up, consign ourselves to a tag of history’s greatest chokers: we would never recover from this. United, despite being an average team, and desperate enough to have a midfield three with a combined age of 108, were going to win a 20th title. Worlds turn on such moments. I would have cried if I hadn’t been so numb. I got up from my chair and went to lie down on the bed. I stared at the ceiling. After all this stress, we weren’t going to do it.

But much like in that Gillingham game, when Dickov scored that club-saving goal, the universe realised that we had had to take enough of being shit, being maligned, being lesser than. In the 92nd minute our hard-working and determined striker Edin Džeko scored to equalise. But I didn’t move, it felt even crueller, to be one goal away from the title. United’s game finished, they had won their match and were ready to start celebrating. Thirteen seconds passed between the end of United’s game and what happened next. Before another thought could even get into my messed-up head, the commentator started screaming. AGUERO!!!!! GOAL!!!!! With the last kick of the season our handsome, talented, absolutely no trouble, striker Sergio Agüero , the son-in-law of Maradona no less, made time stop as he skipped round Nedum Onouha (QPR defender and lifelong City fan) and decisively blasted the ball into the net. Off his shirt came and absolute hysteria erupted . I jumped off the bed, sank to my knees and started to cry, simply praying for the final whistle. One long minute later, we were champions of England.

My phone lit up like an Xmas tree, and I talked to some friends through sobs. I called my dad. We shared our total disbelief of what we had just heard/seen. We were simply and genuinely in shock. This doesn’t happen to us, this kind of blinding triumph. We’re famous for getting it wrong, for falling down, and we always lose. United always have the last laugh. I was delirious. Without thinking, I booked a train ticket to Manchester, after calling the local radio station and confirming that the victory parade was on for the day after, and just floated to Euston. I was home in time for Match of the Day, which we watched half in joy, half in tears. I met dad at 4pm the day after in town and we got a spot among our fellow blues in Albert Square, in front of the Town Hall, a most stunning building. We were with our people. I’ve never seen so many scallies in all of my life. Yes, they’re chavs, but they’re my chavs! There were babies, toddlers, little ones, teenagers, students, mums and dads, middle-aged couples, pensioners – to a man, woman and child they were in joyous shock. Everyone had their match-day tale. For the players, it looked like this . To my eyes, it looked like this:

like this

this

this

and this.

Truly, it was one of the best days of my life, of our lives – to share this with dad was unimaginably special and momentous. We dragged ourselves home, and I was so excited I actually tripped and fell up my own front steps. But that was it, the day that marked the end of Cityitis, the day that consigned Typical City, always screwing it up, to history forever. And yes, dad is going to keep his word on the beard bet.

So, exhausted, I got the train home this (Tuesday May 15th) morning. But that’s not even the end. I had a reserved seat, but for some reason kept walking and sat one coach down, for no particular reason. With 10 minutes to go of the journey, I got up and turned towards the rest of the carriage.

My gaze alighted on two very handsome men sitting two seats behind me. And then I had this moment. My City shirt registered on his face, which broke into a warm smile of recognition, my brain registered that I knew him and in a split second I realised that it was Kolo Touré, the City defender, who was looking back at me, sitting next to his youngest brother Ibrahim. Not all footballers are the same, and from the press you’d sense that most are boorish drunken hooker-shagging oafs. This guy, from the Ivory Coast, a civil-war-torn country, has always been different. He has always been a model professional, and he has always behaved in the correct way. Last year he made a mistake: he was so worried about his weight (despite looking like a Greek statue) that he took his wife’s diet pills, failed a drug test and was banned for six months. He took it on the chin, apologised (even though the team doctor had told him the pills were fine to take), never complained, and worked his arse off to stay fit. After his ban ended, he returned as a squad player, and was welcomed back with open arms. Fellow defender Joleon Lescott had usurped him in the team, taking his place in his absence, and he never complained. His younger brother Yaya had become the team’s heartbeat, totally overshadowing him, and he never complained. He never went crying to the press, and he never banged on the manager’s door demanding why he wasn’t in the team. When our majestic captain Vincent Kompany was banned for four games he slotted into the team and held the defence together. When Kompany returned he again went to the sidelines, and he never complained. When Lescott was injured, without a word he took his place and played superbly. When Lescott was fit, he lost his place again and he never complained. He is a team player.

So when I saw him, it didn’t occur to me to do anything but what I did. We exchanged a look of two people who, despite not knowing each other, had been through something together. I held my hand out, and he shook it. I burbled something – I think I told him how long we had waited for this moment, how old my dad was when we last won the title, how old I was and how I thought this day would never come – and I looked him in the eye and just said thank you. You don't know what this means to me, to my family, to all of us. He was kind and gracious. I shook his hand one more time, thanked him again, and walked down the train. Imagine that, to get a chance to personally thank a hero: I will never forget it. I called dad immediately, who was incredulous that I’d met him and that he hadn’t been sitting in first class. I then bumped into a guy who said ‘Did you see Kolo? He’s in that carriage, in standard class?!’ Footballers are reviled, honoured, worshipped, envied and hated. They’re millionaires, and we’re surprised when they behave like human beings. This last couple of days I’ve seen players strain every sinew to do something for fans like me. I don’t give a fuck how much they’re paid or how much we’ve spent. They did this for us. And today, the city is ours.

...