Hartsfield’s Landing: a West Wing story about how much your vote matters

It’s been a hard year. People are reaching out for comfort. You might have remodelled a room, bought new art, a rug, plants; got new clothes, even though you have nowhere to go; hunkered down to watch TV, as we face whatever the fuck this is and is going to continue to be.

How can money be sucked out of you? Pay-per-view football, a live-streamed gig (remember gigs?!), benefit for a struggling theatre, donation to a food bank or community food project? Are you bereaved? Working, furloughed, made redundant or on the dole? Getting government money, barely enough to survive on? (which you – not the rich – will be repaying via higher taxes for the next two decades) Or have you fallen through the social support cracks into anxiety-induced near-penury?

The roulette wheel spins, we pick and yet… sameness. A tiny event like a distanced visit with a loved one marks out a day. You pounce on any work offered, as who knows when the next will come. Talking a walk in a wood or park near home, if you don’t have a garden, has become important, and yet it takes a gargantuan effort to muster any energy to go out. Out in shops or on public transport, on overloaded buses, half-full tubes or empty commuter trains, you weave around the chin and nose cunts, too self-absorbed, too selfish, to notice or care about fallen masks. Recipes distract, it’s a surprising interest in cooking a passable version of food you can no longer order in restaurants. An acceptance that there will likely be another year of this shit. Who knew the end of the world as we knew it would be so… slow.

In reaching out, maybe you (re)discovered something that doesn’t remind you of all this. John sang, ‘whatever gets you through the night, it’s alright’. Me? Buffy again. The warm, delightful Schitt’s Creek. The viciously good Better Things. And partly because of [i]all this[/i] and partly because of White House occupancy, a walk back to the warm hug of how American politics can be of The West Wing.

I’m not sure any other show inspires such devotion and blame. American journalists are obsessed with ripping it up, as if it actively harmed their country. It’s dated, smug, preachy, a liberal fantasy, or an act of self-harm so egregious you’d think people voted for the White House’s occupant because Toby Ziegler chewed a cigar and expressed a progressive opinion that social security could be saved for generations, healthcare should be available to all and university tuition should be tax-deductible (an idea so left-wing it was backed by Rand Paul, one of the most viciously right-wing/libertarian politicians). TWW has a huge amount in common with the sweeter small-government politics of Parks and Recreation, a show that never got called a liberal fantasy, despite being exactly that (with showrunner Mike Schur massively influenced by The West Wing). It might come down to creator/head writer (for the first four of its seven seasons) Aaron Sorkin, the Bono of screenwriting. Journalists hate that guy. Yes, The Newsroom was bad; yes, Studio 60 was flawed but watchable; but The Social Network, Molly’s Game, Sports Night, Moneyball, Charlie Wilson’s War, A Few Good Men, The American President and The Trial of the Chicago 7 are all very good indeed.

Such hatred is based on a shallow understanding of The West Wing. The administration achieved… very little. There is no triumphalism; they don’t remake America. They were blocked by Republicans (portrayed as John McCain types, not venal Mitch McConnell types, at least during the Sorkin years), blocked by themselves and blocked by circumstance, incompetence, arrogance and hubris. Yes, they are sexist. The sexual harassment in the boys’ club workplace is sometimes borderline, sometimes blatant. But the idea that Sorkin painted perfect characters and we should all wring our hands over the damage they did to liberal causes because of their implausible idealism, and that we should stop trying to make America like this, is naïve. It’s not like those who love it are blind to its flaws. The West Wing Weekly podcast calls out those flaws in detail. But it also posits that, especially given the trauma of the last four years, politics can be different. Why not? What’s wrong with a bit of hope?

TWWW, co-presented by podcaster Hrishi Hirway (Song Exploder) and former cast member Josh Malina, started in March 2016 and was a deep dive, with episode breakdowns and interviews featuring ex-cast members, guest stars, technicians, producers, writers, directors, famous fans and a whole bunch of experts – senators, speechwriters, military figures, press secretaries, chiefs of staff and more, most of whom worked in the real White Houses of the last 40 years. These were political operatives from the administrations of Nixon, Carter, Johnson, Reagan, both Bushes, Clinton (whose White House the show is largely based on) and Obama (whose staffers told the cast they went into politics because they grew up watching The West Wing). If you like to know how things are made, if you want to be inside baseball, as they say, it’s a wonderful insight.

The West Wing is a relic, as are other late-90s-early-2000s shows about cops, lawyers, doctors and aliens (and by the way, nobody writes articles saying The X-Files damaged America because it popularised conspiracy theories and pushed them into the mainstream, even though arguably it did).

I don’t doubt that getting the band back together for the podcast is part of the reason that Sorkin, who gave TWWW his full, grateful participation and appeared in many episodes, decided to come back for a one-off reunion episode to benefit When We All Vote (it’s supposed to be a nonpartisan organisation but I don’t see any Republicans in its ranks apart from a few local mayors; nevertheless, the episode raised more than $1m for it). And so, in this era of visors and distances, most of the cast of The West Wing got together in LA in September and filmed a staged reading of season three’s Hartsfield’s Landing. It is, simply, about how important it is to vote, with side plots of a chess game (figurative) with China and Taiwan, and two chess games (literal) between the president, Josiah Bartlet (Martin Sheen), and two of his staff, Communications Director Toby Ziegler (Richard Schiff) and his deputy Sam Seaborn (Rob Lowe).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g868M-27qpI

I got an evening of it going, first watching the 2002 original to play spot the difference. The 2020 version started thus, with Bradley Whitford (Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman), now a multiple Emmy winner, giving a bit of charming side-eye, fully aware of the ridiculousness of the entire enterprise: “We understand that some people don’t fully appreciate the benefit of unsolicited advice from actors. We do know that. And if HBO Max was willing to point a camera at the ten smartest people in America, we’d gladly clear the stage for them. But the camera’s pointed at us. And we feel at a time like this that the risk of appearing obnoxious is too small a reason to stay quiet if we can get even one new voter to vote.”

We were off. All the setups are on the same stage, LA’s Orpheum Theater. The design, deceptively simple, is stunningly directed by the executive producer of the Sorkin years, Thomas Schlamme. He is the ‘walk’ of the famed ‘walk and talk’. It asks whether a TV drama can be broken down, reverse-staged: usually plays become films, not the other way round. The dynamic energy of the 2002 episode is brought about by camera movement and the actors’ physical movement, as they rush from office to office… now, in 2020, nobody goes much of anywhere, and the power of the setting is allowed to come through, which lets the actors, cameras, plot and even the chess pieces settle. That comparable stillness is what makes sure the dialogue sings even more than it did first time around.

On first watch, I found it all so moving. Eighteen years have passed. Some of the women look different but the same, in the way that Hollywood insists women’s faces must look. The men look genuinely older, greyer, more worn (even Rob Lowe). But certainly, the political devastation of the last four years sees the toll written on each face. The lines were delivered with more anger in 2002; this time there’s weariness, a resignation to the mileage taken on. Adding poignancy, one role had to be recast, because of the passing of John Spencer, whose Chief of Staff, Leo McGarry, was TWW’s heart. Leo was transformed into a younger version, played very differently by Sterling K Brown (Sorkin said if he ever rebooted TWW – making clear he would never do so – Brown should be the president). Brown did a great job: being nothing like Spencer helped both him and viewers disassociate from the overall sadness of the lost cast member.

On second watch, beyond how lovely it was to see them all together again, I remembered how sharply funny so much of Sorkin’s dialogue is, even in tense moments. To leaven the China plot and the big finish, a heavy chess game between Toby and the President, there was a lighter chess match with Sam, wherein the machinations of the diplomatic dance between China, the US and Taiwan were played out like real-life Battleship. There was a very funny thread, where press secretary CJ (Oscar winner Allison Janney) and Charlie (Dulé Hill, the youngest cast member – now 45 – the president’s ‘body man’, an executive assistant) battle over a missing paper schedule, which escalates into a prank war that puts the life of a goldfish in danger. We also wisely avoid the fairly inappropriate workplace flirtation between Josh and his deputy Donna (Janel Moloney), who get the title card plot. Hartsfield’s Landing – based on two real towns in Bartlet’s home state, New Hampshire: Hart’s Location and the brilliantly named Dixville Notch – is where 42 voters will cast their ballots at midnight: the town has been historically successful in predicting the general election winner, so these 42 votes matter. There is a plot hole big enough to drive a truck through here, wherein we are half a season away from the general election (Bartlet beats Rob Ritchie, played by Barbra Streisand’s husband, James Brolin, to win his second term) so what are they voting for? It can’t be to choose Bartlet as the candidate because he is running unopposed so wouldn’t be on the ballot. But… we gotta let it go.

Josh It is absurd that 42 people have this kind of power.

C.J. I think it’s nice.

Josh Do you?

C.J. I think it’s democracy at its purest. They all gather at once…

Josh At a gas station.

C.J. It’s not a gas station, it’s nice. There’s a registrar of voters, the names are called in alphabetical order, they put a folded piece of paper into a box. See, this is the difference between you and me.

Josh You’re a sap?

C.J. Those 42 people are teaching us something about ourselves: that freedom is the glory of God, that democracy is its birthright, and that our vote matters.

Josh You’re getting the pizza?

C.J. Yeah, I should call ahead.

The show said it best: “Decisions are made by those who show up”. And so, Josh elevates 42 votes to a place of high drama and high importance. Not just because politics is a superstitious game, but because every vote does count. A couple he met on the campaign trail, the Flenders, have called Donna to say that they are thinking about voting for Ritchie. She is sent out into the cold with a mobile (yes, even in 2002!) to try and persuade the Flenders their two votes matter. Back and forth it goes:

Donna They think the President is going to privatise Social Security.

Josh He’s not going to... That’s the other guys! He’s not going to privatise Social Security! He’ll... He’ll privatise New Hampshire before he privatizes Social Security!

A side note for the nerds: this remake takes a deep-dive into the supporting cast from the original. The journalists in the press room, all in multiple episodes, are recognisable to long-term fans. CJ’s aide, Carol, is there – played by Melissa Fitzgerald, she quit acting and founded Justice4Vets, an org which campaigns for veterans’ treatment courts. The China plot brought back the wonderful Anna Deavere Smith, who as well as being a brilliant actress (and professor) is a Pulitzer-nominated playwright: her one-woman show about the prison-for-profit system, Notes from the Field, played off-Broadway and at the Royal Court. She took no part in TWWW, purely, we were told, because of being too busy so it was a real pleasure to see her again.

Reading the scene directions [Cut to: Int. Josh’s bullpen – Night – Donna comes in, wrapped in a long coat] (that sort of thing) was the brilliant Emily Proctor. She joined in season two to play a Republican operative, Ainsley Hayes. President Bartlet’s nature was to be interested in those who disagreed with him, like Lincoln’s ‘team of rivals’ (as described by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin), so he hired her. But there were, as Sorkin put it, ‘too many mouths to feed’; Procter was offered another job (CSI: Miami) and left for a bigger break. He regretted not making space for her, and I’m certain that’s why she appears (rather than any attempt to reach out to Republican voters). Hayes presented a realistic face of conservatism that never sneered, not even when she argued against the Equal Rights Amendment.

The episode’s big storyline, though, is Toby’s chess game with the president. The scene, simmering, comes to a boil with a question about what voters want. A guy they can have a beer with? A rich guy they’ve been conned into thinking isn’t elite? The smartest kid in the class? Watching that scene makes you recoil, knowing what we do about who sits in the Oval. While Bartlet has had enough of Toby, Toby has had enough of tiptoeing around the idea of whether a candidate should be ashamed about being smart and capable.

Toby Abbey [the First Lady] told me this story once. She said you were at a party once where you were bending the guy’s ear. You were telling him that Ellie [his middle daughter] had mastered her multiplication tables and she was in third grade reading at a fifth-grade level and she loved books and she scored two goals for her soccer team the week before, you were going on and on... And what made that story remarkable was that the party you were at was in Stockholm and the man you were talking to was King Gustav, who two hours earlier had given you the Nobel Prize in economics. [laughs] I mean, my god, you just won the Nobel Prize and all you wanted to talk about to the King of Sweden was Ellie’s multiplication tables!

Bartlet What’s your point?

Toby You’re a good father, you don’t have to act like it. You’re the President, you don’t have to act like it. You’re a good man, you don’t have to act like it. You’re not just folks, you’re not plain-spoken... Do not, do not, do not act like it!

Bartlet I don’t want to be killed.

Toby Then make this election about smart, and not... Make it about engaged, and not. Qualified, and not. Make it about a heavyweight. You’re a heavyweight. And you’ve been holding me up for too many rounds. [Toby lays down his king on the board. Bartlet stands and turns to walk out.]

Bartlet Pick your king up. We’re not done playing yet.

That scene is incredibly powerful. It was in 2002. And it’s 100 times more so today. Sheen and Schiff are remarkable, two heavyweights slugging it out, a masterclass in tone, emphasis, balance. There is, it’s been said before, real music in the cadences of Sorkin’s words.

We know it should work like that. Because being president is a serious job and these are serious times and elevating an unserious person to its heights is disastrous. Who sits in the White House is always… a mirror. This is a bleak moment in American history and we all know the conservative side suppresses voting because they benefit when fewer people vote. So we must hammer the idea every time even if it never changes turnout: voting is a right and should be widely accessible.

In the end, with the Flenders and their economic anxiety, Josh gives in, saying ‘let ’em vote…’ And the lesson is done. This show is about public service. It’s not a harmful bubble to live in for 42.5 minutes. Between scenes, where ad breaks usually go, are unsubtle messages about voting from Michelle Obama, Bill Clinton, Samuel L Jackson, Elisabeth Moss (who the show discovered, she played the Bartlets’ youngest daughter), Lin-Manuel Miranda (a serious TWW nerd, he and Hamilton director Thomas Kail did a special TWWW episode and his last Hamilton curtain call was done to TWW theme). There was a return for the iconic Marlee Matlin (who played pollster Joey Lucas), the only deaf actress to win an Oscar, who looked beautiful: and looked her age. Her bit with Whitford was on why voter fraud is nonsensical, how it doesn’t and cannot happen. Some of these sections are serious, some funny, some pointed, especially interjections from Jackson and Black cast members Dulé Hill and Sterling K Brown. In a glowing review of the special, Vanity Fair’s TV critic said the show ‘feels so removed from reality’ but she said that out of sadness, rather than criticism. Buying an idea/myth of politicians acting in good faith isn’t a failure of The West Wing. You should believe that, even if it feels we’ve gone far away from Obama’s optimism into today’s cynicism. We should all know that – and this goes for politics and pandemics – it won’t always be like this.

To end, this clip (from earlier in the third season) is on the nose. It’s the worst of Sorkin if you can’t bear him, the best of Sorkin if you get him. And call me a sentimental old fool if you want, but I love it. In it, a leak has embarrassed the President and Toby assembles the junior staff. The audience expects him to be angry, take the roof off, with a lesson about loyalty. He does the opposite, and even out of context it’s… what the show is all about.

The West Wing.

It’s just a TV show: lighten up, don’t take it seriously.

It’s not just a TV show: it matters, and it has changed lives.

It’s okay for both of those things to be true at the same time.

Final note: The West Wing Weekly’s special episode on The West Wing’s reunion special

Bohemian Rhapsody – 2 stars

Biopics are not easy to get right. Squeezing an entire life into two hours, with commercial considerations banging on the door… meaning, it usually has to be a PG13/12A rating, and you have a big story to tell, often of sex and drugs and rock and roll. Nine years in the making, with three leads, three screenwriters, two directors: these are not the ingredients that result in a gratifying portrayal of a human life. And with Freddie Mercury, lightning in a bottle personified, it was always going to be a fool’s errand. It’s a two-star film, at best, with a four-star performance. Rami Malek’s virtual channelling of Mercury just barely saves the film from total disaster.

First off, there’s a problem with what they’ve chosen to include: half the film is set in the 70s, and there are lengthy sequences of recordings, including of the nonsense masterpiece the film is named after. There are some people – myself included – who find the inner workings of recording studios grippingly fascinating. But I imagine the majority of an audience wants to see something else, even though I found those scenes fun, mostly because I was listening out for different vocal takes and such like. No doubt putting that much music in is a done deal when you have band members producing a film, but it doesn’t make for terribly interesting scenes. A great many exciting events happened to Queen, from their formation in 1970 to their sad, enforced end in 1991. With their first album out in 1973, the band recorded music for only 18 years, and Mercury has been gone for very nearly 27. So it seems cynical to attempt a biopic now, after all these years (original Queen fans + their offspring = double the audience), and the controversy, and firings, around it have hardly helped to cement a consistency of storytelling. Bryan Singer (who will shortly have an Esquire article expose him as a predator) has tried to do a good job, with help from the underrated Dexter Fletcher. And it is nearly impossible to cohere multiple satisfying narratives into two hours, especially with the subject gone. But there is no reason for the script to be this terribly poor. It shouldn’t be, with The Queen showrunner Peter Morgan’s original bolstered by The Theory of Everything’s Anthony McCarten. Why is it so bad? Freddie Mercury was passionate, generous, gifted, very funny, sometimes difficult and, yes, sex-driven, with a side of shy and vulnerable, and this is a meek, painfully sanitised exploration of his private life. I’m not saying I wanted the bathhouse-based director’s cut, but a bit more bite would have been great. His seven-year romance with his lifelong muse, and the woman to whom he left his grand home and half his wealth and royalties, Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton, doing well with bad writing) is covered in endless detail. Austin has not played any part in this film, understandably; indeed, since he died she has given only a handful of interviews, and her relations with the rest of the band, his friends and family are said to be tense. With one person gone, and the other unwilling to discuss the reality of a private relationship, the scenes between Malek and Boynton feel like basic coming-out-story melodrama, when the reality must have been much more complex. It is important to note that Mercury’s bisexuality is not washed over, at least. And nor is the gay side of his life, later on. It’s also correct that Austin should be given the credit and legitimacy in his life that she deserves, but it’s all rather bloodless. It also means that, unfairly, less importance is given to his relationship with the late Jim Hutton, the Irish barber (here a waiter, why?) who he also shared his life with for seven years, until the end. You can’t get private moments right without input from those who were there, of course, but they don’t even get close to making a decent job of it. The Hutton storyline is undercooked in the extreme, little more than a footnote, which is insulting to his memory, too (he died of cancer in 2010, aged 61; when Freddie died Mary had him evicted abruptly from the home they shared for years).

The band, even today, seem uncomfortable with his sexuality, with a recent interview with May discussing his ‘men friends’ alongside Austin. Understandably, if you lose both your friend and your career overnight it’s not something you ever get over. I’m just not sure that that discomfort should be shared beyond boilerplate rock-star autobiographies: such coyness has no place influencing the content of a film that’s should have largely not been about you. Brian May (Gwilym Lee) is hardly a ripe character for a biopic. He may be a musical god, but he’s a gentle, quite dull man who cares more about badgers, physics and stereoscopic photography than any person should – Lee manages to do miracles with the character, frankly. His dry humour comes across nicely. While bassist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello; the little lad from Jurassic Park, trivia fans) is imbued with a rather surprising amount of subtle personality by an actor who’s been doing his homework. But drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) should have been made much more of; he’s a spiky, no-bullshit, Tigger-like presence in real life, and his closeness with fellow hedonist Mercury doesn’t come across at all. The character is dull, and the actor is too, and it does Taylor a disservice. Let’s not talk about Mike Myers, in his Jeff Lynne costume. He was amusing as a composite character of a snooty record exec and their first manager Norman Sheffield. But he just seemed to be there so the band could say, ‘thanks for making the song big again in America via Wayne’s World.’

As for the ‘straightwashing’ the trailer was accused of: I didn’t find that to be true. I wasn’t expecting a Caligula-esque series of scenes set in London’s iconic 80s gay club Heaven, or any one of the myriad Munich bars that he spent most of his nights in starting from 1979 or so. A big studio picture is never going to allow that level of exploration of gay life, especially with the spectre of Aids hanging over the film like a black cloud. It did feel like a series of missed opportunities, however, to rip open the virulent media-led homophobia that he faced his whole life, and his fear of being outed.

Also a missed opportunity was a more rounded storyline for the villain of the piece, Paul Prenter (Allen Leech). One can’t libel the dead, and this snake should have been written with much more narcissism. He drew Mercury away from the band and into drugs and long nights in dark rooms that ultimately proved his undoing. Glossed over, too, was his heartbreaking betrayal of Mercury, which he never recovered from. He sold his story to The Sun for £30,000 in 1987, outing the singer in the process (in the film this was a fictitious TV interview where he slings a racial slur at Mercury: never happened). Prenter may as well have a neon sign saying ‘danger: I can’t be trusted’ hanging above his head, but this terrific actor is wasted in an underwritten part. Two more great actors do wonders with average parts: Aiden Gillen does the best he can as the band’s 1970s manager John Reid, while Tom Hollander as Jim Beach, who guided the band at their imperial 1980s peak, does sardonic well. But everything should be sharper: the drama, writing, plotting.

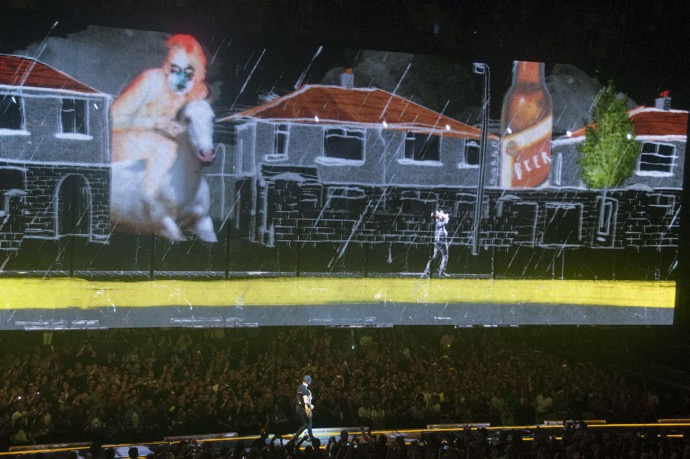

One faultless aspect of this flawed film is the musical sequences. In this, we get perfection. The swirling, thrilled, sweaty crowds; the peerless music, sometimes overblown to the point of laughter, sometimes achingly beautiful, always decadent, works a treat. The live concert scenes are handled with great skill by Singer. These details, speaking from a fan’s perspective, are spot on. From the costumes to the settings, the performances are finely tuned. And Rami Malek comes close to saving the whole movie, somehow. The depth of understanding from this fine actor of his subject is critical. Immersion in such a life only works if your subject was layered, thrilling company, and it helps if there’s a creditable, exciting, possibly tragic, story to build on. Malek is given all that raw material to work with, and he runs away with it. There is no shortage of drama and dynamism and power on show. Embodying a beloved person is an impossible job, one that can go wrong without the right focus, or can veer too much in a Stars in Their Eyes direction. To inhabit a rounded portrayal of a real man, with very little offstage material to go on (Mercury did precious few interviews), is not an easy task, but Malek pulls it off and then some. He captures a perfect mix of bravado and vulnerability. The script makes a cheap shot about ‘having not enough time left’, sold to us as prescient but it made my eyes roll, yet he still manages to imbue these moments with the ending we know is coming, of a life over at 45. He beats the thin script into a pulp with sheer force of will. In particular, the big finish of the film, a full-length recreation of the band’s Live Aid performance, is breathtaking. I have no issue with the lack of descent depicted, that the film ends in 1985 rather than going toward deathbed drama. There are plenty of films, and documentaries, that show the cost of Aids in grisly extreme detail; it’s not needed here. And for those of us who lived through it well enough at the time, traumatised by seeing this extraordinary man turned into bones in front of our eyes, there is no need to portray it here for prurient interest. If you want to see what happened to Mercury, his devastating end, the video footage is available. It was a smart choice (badly handled, as I’ll get to later) to end the film at his life’s professional peak.

Much like the tedious Queen musical, We Will Rock You, here the music works and not much else does. And for Malek, it’s the star-making performance of a lifetime. But if you let a band produce a film about themselves it will have music-making, and their version of events, as its centre, rather than a truthful core about the person who has no ability to reply. Worst of all, the falsities on show here mostly in the final third are wild and reckless. And there is no need for them: his life was a thrill-ride without the need for embellishment. If you’ve gone to that much trouble to get a piece of recording studio equipment right, or the correct Japanese light in a recreation of his house, then why on earth would you allow complete lies to be in the film? I don’t mean something like a gig showing him crowd-surfing: that’s in the film, it was apparently not in the script; Malek just did it. Mercury never did that in his life. There are tons of small things like that which are wrong. That’s fine, a bit of exaggeration, who cares? It’s not a documentary. But the big stuff, you have to get it right.

The remaining band members’ judgement looms large: we’re normal Freddie, we have families, you have to slow down. Never mind that May cheated on his wife with groupies multiple times and just after Live Aid left his family. Never mind that Taylor shagged everything on the road that moved, unable to create any sort of stable relationship for decades. Oh, it’s Freddie and his ‘appetites’ that are destroying the band. They’re having normal heterosexual sex: the kind of sex Freddie has is the wrong kind. Their resentment of him beams through. I always thought it was grief. That the loss of their friend was something they never recovered from. It’s not. It’s anger, at his gayness destroying their careers. And it culminates in changing the truth for their own ends. And incidentally, if Brian and Roger are going to make a big deal about how Freddie’s solo career put the band in jeopardy, they might mention that they had already made three solo albums between them by that point. His solo record came out after Live Aid, not before. It’s one thing to put in a stupid press conference where Freddie is pressed on his sexuality while high (never happened). It’s a badly written scene but changes nothing that’s materially important. It’s another to indulge in a parallel universe fantasy.

And that leads me to the biggest, and most insidious, lie in the film. He is given his HIV diagnosis, for dramatic effect, just before Live Aid – as fuel for that career-defining performance. The real diagnosis happened two years after. This is sick, distasteful stuff, as is the fictitious meeting with an Aids patient covered in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions outside the doctor’s office. What were they thinking? Everyone involved in this film should hang their heads in shame for making it happen. The band has thrown their friend under the bus to make themselves look good and benevolent for letting him back in the band (never happened).

He put on that 20-minute performance of his life at Wembley Stadium because he was fucking remarkable. Not because he had been told he was going to die. This messianic trash, this ‘I’m going to die for you, audience’, cheapens the power of the scene, the film, and worst of all it cheapens his life and death. Malek plays it, despite it being nearly shot-for-shot, with a determined face: I’ll make this the show of my life because I have limited time left. Watch the real thing.

It’s not determination. It’s joy. It’s conviction. This guy knows he is doing the 20 minutes of a lifetime. A year later he is said to have started to feel unwell, telling everyone the tour they undertook was to be his last. He avoided tests, in fact, for another year, out of fear. Then he was calm about it, wanted no sympathy. Just wanted to get on with it, make music until he dropped. This is an era of ‘my feelings matter over your facts’. Well, no. Facts matter.

This Live Aid fantasy was the filmmakers’ insulting solution to dealing with his illness? They made the correct, quite brave, decision to not do his death onscreen. But the fix for this problem was not to openly lie. It was not to create an alternative timeline that ruined a good idea with a bad one.

It could just have been a post-script: you don’t change history and a person’s literal HIV status for show. It could also have had a braver end: Hutton was backstage at a Queen show for the first time, and Freddie was in love, after being lonely, and taken advantage of by hangers-on, for so long. Finally, he’d found someone to whom he could come home to, who nursed him to the end. But I guess a gay love story isn’t going to sell the way the fake inspiration of illness does. It makes me so angry that people will watch this and think it’s true. I hope they seek out what really happened, I hope they seek out the real thing and consign this version of events to the bin. Freddie Mercury deserved better than this film.

Girl from the North Country – Written and directed by Conor McPherson. Music and lyrics by Bob Dylan.

This review, which contains spoilers, ran in Issue 194 of Isis, the Bob Dylan magazine.

Artists who diversify have sometimes been viewed with suspicion. An actor makes music? Bruce Willis crooning Under the Boardwalk springs to mind (don’t bother). A rock star makes a movie? Mick Jagger played a mercenary in Freejack (really, don’t bother). David Bowie’s last work, Lazarus, was a sprawling, experimental piece of theatre which used his songs in a dynamic, thrilling way. But would the play have worked without the music? I don’t think so, and I saw it workshopped in New York and then tightened up in London. In fact, after seeing Girl from the North Country, I wished that Conor McPherson was the Irish playwright that Bowie had engaged, rather than Enda Walsh, the one he did. Because while Lazarus could not stand easily on its feet as a play, Girl from the North Country certainly can. There were a couple of ill-judged parts, more of which later, but on the whole this was a dazzling night at the theatre.

It’s 1934 in Duluth, our man’s birthplace. The Great Depression has taken hold and casts a chill over proceedings like the local cold. The parallels between Dust Bowl America and our own recession, turned into cutting, cruel austerity, are marked. The narrator (Ron Cook), a doctor, introduces us to the scene, and provides grounding throughout. We are in a guesthouse, leaking money and about to be put into foreclosure, run by Nick (Ciarán Hinds), a gruff man with a complex life: a wife with dementia (Shirley Henderson); an adopted African American daughter (Sheila Atim) who is seemingly pregnant at 19 by someone long gone and also being pursued by a predatory, creepy old man (Jim Norton); and a layabout son (Sam Reid) with his head in a whisky bottle most of the time. He has a mistress (Kirsty Malpass, stepping in from the ensemble, superbly), who asks for little, and can’t stick around much longer in this desperate economic climate. We meet a variety of dishonest lodgers, tempers fraying, trying to eke out a living in impossible times.

The dialogue races by, each strand woven together masterfully. I was gripped by the intensity of the storytelling. And then, there’s the music. I thought, how on earth could this work? Will dropping a bunch of Dylan songs into an autonomous play distract? Will Americana arrangements suit? Will the choices make sense given that they can’t further the story? After all, he didn’t write these for the play. And then the first song, Sign on the Window, drifts in and wow, just wow, it all coalesces better than I could have dreamed. A hipster-looking (1930s beards/attire is twenty-first century hipster chic) house band (double bass, piano, fiddle) accompanies the actors, who take turns on percussive instruments. Twenty songs are used to soundtrack lives of anger and passion, sadness and regret, worry and loss. I was sometimes taken out of the moment, if briefly, to reflect: this song is part of me, part of the fabric of who I am. But then a second later I was locked back in to 1934 Minnesota. It’s a tightrope walk and McPherson, previously known for his supernatural works, has aced it. There are no easy choices here: you try and pick 20 Dylan songs out of them all to accompany a plot organically and soundtrack this highly strung chaos.

The performances are remarkable, particularly Henderson as Elizabeth, Nick’s wife. She gives an untethered lightness to the role that is sure to win her buckets of awards; I predict the Olivier for Best Actress. Physically slight, and 51 but looking two decades younger, she is a mismatch for a big man of 64 like Hinds. They don’t convince as a couple in that sense but there is genuine chemistry between them as he tries to cope with her disinhibited behaviour towards the guests. There are no weak links in the company, with Sheila Atim in particular owning the stage during both dramatic and musical moments as a woman who everyone wants to control. Her version of Tight Connection To My Hearttook my breath away; nearly unrecognisable, it is all the better for it. As the stories interlink, and there is much to weave in, we come to a couple of troublesome moments.

A young African American man arrives (played flawlessly by ensemble player Karl Queensborough) and reveals himself to be a boxer just out of prison, so he says. This is a pretty clumsy way to shoehorn Hurricane in later on; it didn’t fit, at all. In fact, after a tight first half, it came off the rails, briefly, shortly into the second. It almost felt like McPherson had lost his own threads and, while he tried to find them, shovelled in a couple of songs that didn’t fit. He pulled it all back together but then took the only major misstep in the play, a storyline of parents and their adult disabled son.

Portraying disability is not easy, and unless it’s central (like in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time) it’ll come across as throwaway or played for effect. The actors in this plotline were fine enough, with the mother in particular (Bronagh Gallagher) compelling. But a confusing blackmail scenario with a menacing Bible salesman (Michael Shaeffer) led to exposure of their ‘secret’: the son had sexually assaulted a woman and the family had to flee. Their section ends with the father, at the end of his tether, letting his son drown. Then, appearing as a ghost in white clothing, the son (Jack Shalloo) returns to render a gospel-tinged rendition of Duquesne Whistle. None of it worked and such a portrayal of disability was inappropriate and veered to the offensive given that the ghost was miraculously cured of his learning difficulties. This inherent condescension was compounded by a regressive decision to cast this character as dangerous in the first place. I tried my best to forget it, because it should not sully the rest of the play.

I’d decided not to spoil any musical surprises by finding out the ‘setlist’. My dad bought a programme and scanned carefully to see which were to be featured. I turned away, much as I had done for Lazarus: I wanted to gasp with surprise when Jokerman appeared (it was the first Bob song I loved; Infidels came out on my seventh birthday). Or grin and feel an inner thrill at the storming, foot-tapping, tambourine-bashing version of Slow Train, making it sound better than it ever has. I’m not going to drone on about voices, and how these singers give new life to the material. But they do. I don’t need to tell you anything about Bob’s voice, its tenderness in these later years mixing with a road-worn timbre (she said politely). Watching excellent actors embody these songs sets light to them, shooting jolts of electricity through their hearts. And quite frankly, it is no bad thing to have an audience become agog at these lyrics because they can actually hear the deathless words perfectly. It all reinforced my great love for this material; you won’t believe how delightful it is to hear Like a Rolling Stone with a snippet of Make You Feel My Love in the middle. A pleasure to hear tracks from each decade too; it would have been easy to make it all 1960s stuff, given its relative proximity to the 1930s – acoustic renditions would have fitted seamlessly. Instead, there are just three songs from that decade, a welcome, gutsy, non-obvious choice.

McPherson has set himself a challenge and pulled it off. He manages to evoke Thornton Wilder’s classic Our Town as well as the work of Eugene O’Neill. He also makes you want to drag Street-Legal and Infidels out of storage. The songs run between 1963-2012, and each one is judiciously chosen. What Simon Hale, the orchestrator/arranger, has done with them will melt you in your seat; simple but ravishing, these often moving interpretations of music you know inside out will make you hear them anew.

Girl from the North Country, described by McPherson as a ‘conversation between the songs and the story’, is full of life. It is about trying to find hope through suffering and making the best of it. Dylan’s ‘team’ approached McPherson to write and direct this play, no doubt having heard tell of his acclaimed works The Weir (which ran at the home of new theatre, the Royal Court) and Shining City. And of course we know that hands-off Bob is never quite hands-off; even though he played no part in the writing or arrangements of the dialogue or songs, he did send Jeff Rosen to attend rehearsals. The last time the canon was offered it was a flop, a Broadway show in 2006 that closed after three weeks. But this time, gold has been struck. I hope Bob gets to see it and I feel sure he’ll be very proud of this inspired play bearing his name.

Donny McCaslin :: Rich Mix, London :: 15th November, 2016

Originally published on davidbowie.com in March 2017

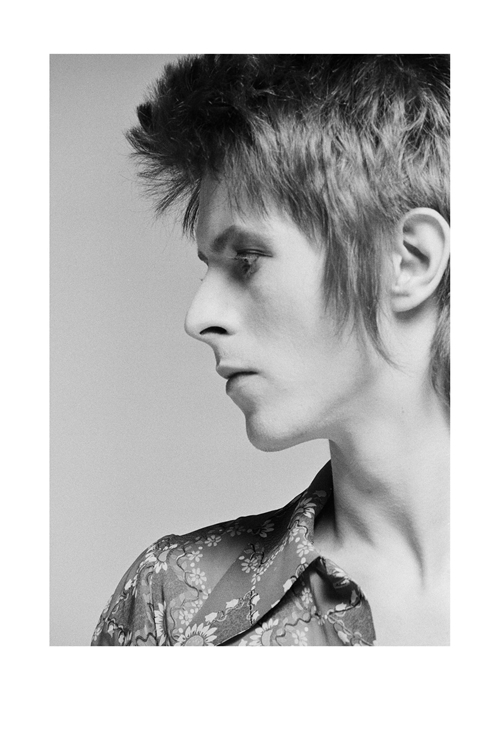

Make no mistake, Donny McCaslin, this genial giant sax player from California, has had a distinguished career in jazz. He’s spent nearly three decades carving out a groove in modern jazz playing, starting with filling the huge shoes of Michael Brecker in the legendary fusion group Steps Ahead. With three Grammy nominations to his name, he’s become the trusted right-hand man of bandleader Maria Schneider, herself a multiple Grammy winner. The dreaded term ‘crossover’ has come to be applied in jazz to artists who break out of the somewhat closed jazz world (closed to mainstream rock/pop fans, in that sense) and make a break across the aisle. In the 70s it was Herbie Hancock who did it, and even before then Miles Davis – the greatest jazz artist of all time – had broken the mould, with Kind Of Blue becoming the best-selling, and most famous, jazz album of all time.

Historically, plenty of pop musicians (looking at you, Sting) have sought out jazz players on their records to give them a bit of cool. And as a lifelong jazz fan, Bowie was no different, taking on saxophonist David Sanborn and trumpeter Lester Bowie to play on his records, among others. Even Mike Garson, of course, is a jazz player. As we all know, Bowie was one of the great casting directors of our time. But beyond bit parts – musicians popping up – he had never given over an entire record to jazz musicians, until Blackstar. Everyone knows the story now. He wanted to continue his collaboration with Schneider after their magnificent foray with Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime) in 2014. But she had already committed to her Grammy-winning Thompson Fields project. So she pressed a copy of McCaslin’s Casting For Gravity into his hand (having sent him this link to a live version of the track Stadium Jazz first) and suggested they visit Greenwich Village’s Bar 55 to see his quartet (with Mark Guiliana, Tim Lefebvre and Jason Lindner). McCaslin says he spotted Bowie sitting at a table with Schneider, tried to keep calm, as you would, and just concentrate on playing. Shortly after, he got an invite to perform on what would turn out to be Bowie’s last album. Since then, one imagines, his feet haven’t touched the ground as, suddenly, this brilliant, powerful quartet have become among the most famous jazz musicians in the world.

During a short European tour, McCaslin’s group (minus Lefebvre, whose regular gig – with the arena-filling Tedeschi Trucks Band – called; replaced by Jonathan Maron) called at Shoreditch’s Rich Mix, packing out the overheated main room and shaking the walls. They’d dropped into London to play some stuff from his new Beyond Now album, a follow-up to 2015’s excellent Fast Future. You could tell the crowd had some Bowie fans at their first jazz gig present; they looked a bit shell-shocked. As I heard someone say, listening to jazz on record is hardly like seeing it live. It’s so much more visceral, muscular, and frankly, louder than you can imagine, especially with a fusion quartet like the one McCaslin leads. The bass thundered. Lindner’s synthesiser textures lent a cosmic vibe reminiscent of the early 70s electric playing of Keith Jarrett when he was with Miles. Guiliana’s complex, intricate drumming evoked the greats; one can feel comfortable comparing him to all-time greats like Elvin Jones and Jack DeJohnette, alongside recent masters like Brian Blade and Kendrick Lamar’s drummer Ron Bruner Jr. That’s how good he is. Get his 2015 album Family First; you won’t regret it.

McCaslin leads this band through twisting and turning renditions of songs new and old. You might have expected Warszawa to be on the setlist; the band closed with it. Less expected but incredibly welcome were two more Bowie songs. First, one that caused the room to experience a sharp intake of breath – Lazarus. It sent a chill, until of course the sax came in where the voice should have been and then it took off, with the closing section containing some absolutely remarkable playing from McCaslin, who was on fire all evening. Then, a lovely surprise, the very familiar drum part of Look Back In Anger kicked in and off we went. The room was electrified. If you’d never seen a jazz gig before, or even if you’d seen 100, this was a top class night.

Lazarus

This symphony

This rage in me

I've got a handful of songs to sing

To sting your soul

To fuck you over

This furious reign

David Bowie – Killing A Little Time

A person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration

Icon (noun) – definition from the Oxford English Dictionary

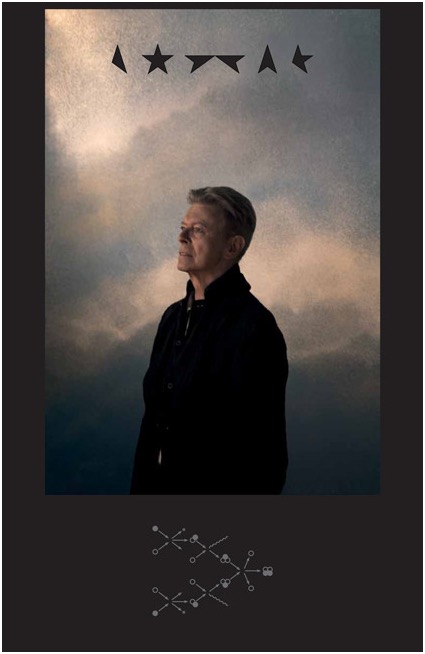

I don’t write much, I don’t write enough. I don’t write unless I need to say something. There was no intention to write about Lazarus, Bowie’s final work, but here we go. Is it his final work? I suppose it’s his joint last work, alongside ★. These works of art dovetailed each other, the play being begun in 2014, the album made in 2015, the play finished off at the same time. Then came the album’s title track in November, following by the play’s premiere in December, and finally, the album in January 2016. They are a Venn diagram of the last two years of his life; the play bristling with anger, the album filled with sadness, creating together the masterpiece of the perfect exit. A lyric, for a song written in 1992, recorded in 2003, springs into my mind:

You promised me the ending would be clear

You'd let me know when the time was now

Don't let me know when you're opening the door

Stab me in the dark, let me disappear

I’m writing this first part the day before I see Lazarus in London, because tomorrow the meaning will change. And unlike ★, which I spent three days listening to (January 8-10) without knowing the meaning was about to be ripped open dramatically, I do know this time that his final work is about to come to me anew.

This is not a review of Lazarus, because others will do that better. Suffice to say, it’s a wonderful, odd and thrilling fever dream of an evening at the theatre. It’s confused and confusing, it’s only really got two great characters (Newton and Girl), and most of the London cast is changed from New York. The theatre is absolutely huge: five times larger, going from the NYTW’s 198 seats to 1002 (unless I’m counting wrong! I thought it was 960…) in King’s Cross. The songs carry it forward, as if he wrote them over a span of 45 years to tell this story. It’s sieved through this character, who he identified with when at his worst during the making of The Man Who Fell To Earth, and who he let follow him throughout his life and chose to ally with just before he left the earth. He sent Lazarus to London in his place. He sent his costumes and lyrics and drawings to London in his place. He sent his art collection to Sotheby’s in London in his place. The 2013 V&A exhibition was a method of ‘touring’, since he had little interest in doing any actual touring, with nothing to gain from appearing on stage. As ever, he created the parameters (choose from my archive, from the artefacts I let you see) and had the V&A curate a retrospective that he visited, quietly, privately, with his family. As ever, again, like the consummate casting director he was, he created the parameters to let Lazarus and ★ keep him alive in perpetuity. ★ occupies a rather physical, tangible place; it’s mostly listened to alone, at home, or during travel, or walking down the street. It’s not a communal experience; it’s not acted out without him and the musicians on it (outside of cover versions, to which I say, too soon!). Lazarus, the play, is a live version of his final thoughts. The actors give you his message, in person. I didn’t know any of this when I was in NYC in December 2015. What was it like then? What can I remember now that will tomorrow be joined by new memories in the hard drive of my brain?

I was nervous, that it wouldn’t be any good. It was ambitious, daring, a mad thing for him to do: a musical, which he’d dreamed of and planned for over 40 years, coming out at the same time as a new album. The one thing he had never done, and now, running out of time, it was the last thing he wanted to do. Gifts upon gifts for me, for us. Seeing it in NYC was a remarkable experience, done twice on consecutive nights. I hardly understood a thing on the first night; it was impossible to take in, the density and complexity of it all. Overwhelming in every way. The second night I got a handle on it, and though I try to shy away from being too literal, those I spoke to immediately after, with heads spinning, already thought it was all about death long before we realised it was about his death. Of course, it’s open to interpretation from all angles and there is no definitive reading (multiple readings, the absence of an authoritative voice and all that). Is the ‘Girl’ character Newton’s surrogate daughter? Yes, the casting call says so (though interestingly she was supposed to be over 18 until they saw then-nearly-14-year-old Sophia Anne Caruso and she dazzled, so the part went younger). If Bowie is Newton, again (as he was in 1976), is Girl a cipher for his own daughter (Caruso is 11 months younger)? I think so. I don’t know so, and I never will. Ambiguity and performance: the two constants throughout a 50-year career. He was never himself, there was always smoke and mirrors. He never explained, and you wouldn’t want him to anyway (not that he didn’t muse on the idea of revealing more over the years before losing interest and moving onto the next new thing).

I don’t want the meaning of Lazarus to change, but it will, when I see it again. I didn’t want the meaning of ★ to change, but against my will it did. A friend told me that he couldn’t get the notion of Lazarus being entirely/only about Bowie’s death out of his head during the play when he saw it at a London preview. Understandable, and that’s what spurred me to write this, as I have the New York version playing in my head and, honestly, how many people will be able to write about seeing it in both cities? One or two hundred? It’s special to me, now, more than ever, the ‘before and after’ contexts. Now Lazarus comes to London, like a morbid travelling version of his ashes. What’s new? So far, what I know is that the brief appearance of a famous actor on the screen has been excised. Good creative decision, as I found it distracting. A too-famous face takes you out of the moment. There’s one more new big creative decision, to put Bowie’s face on screen at the end, which was absent in NYC even after January 10. I’ll see it tomorrow and decide how I feel about it, but my gut feeling (which I suspect I’ll be largely alone in) is that it’s a fucking dreadful, mawkish decision that grates in the worst kind of sentimental, emotionally manipulative way. And for sure, if you knew him at all, you’d know he’d hate that. He refused to have Heroes in the show until Henry Hey re-arranged it so it couldn’t be sung along to (the Lazarus version sounds like the bleakest John Lewis Christmas advert ever). He was not a sentimental man. The subtlety of the references to him inside the play – a few scattered vinyl albums in a corner, a brief snippet of Sound and Vision – were clever, jarring in a good way, and deliciously cheeky. But a photo of him so we can applaud at the end? He’s dead, I get it, I know it, I don’t need to hear a big cheer in a theatre. That brings me to another reason I wanted to write this, to talk about changing fandom and iconography.

It’s been a weird year, in innumerable ways. Setting aside real world life and death and politics and the depressing right-wing rise of what was previously unspoken in polite company, the transformation of Bowie from a live, real human person into this deified dead guy, standing alongside Elvis and John and Amy, has been pretty hard to take. It won’t last, I predict; most people will lose interest in a year or two. His marketable quality won’t match that of Michael Jackson or (what a year) Prince (whose ashes are being displayed in a miniature urn in the shape of Paisley Park, inside the newly opened museum of the actual Paisley Park. Not even kidding). Nor will his rock legend infamy be as long lasting as the murder of Lennon or the bloated junkie self-destruction of Presley. But to make financial hay while the sun shines, the legacy bombardment has started and it’s only the tip of the iceberg of trying to open our wallets. His own estate has many decisions to make about what comes out and when, and at what pace, as they drip-feed us promises of new mixes and alternative takes and so forth. Without Coco in charge, I have little faith that his ruthless, always forward-looking spirit will be honoured. Or more accurately, that business decisions will be made that stop at this red light first: ‘would he have been ok with this coming out? Would he have been ok with me saying/writing this?’ In the pursuit of money, and in the cloudy heads of grieving family, I’m quite sure that plenty of stuff is going to happen that I don’t like. And that’s just from the people who actually knew him.

The next category – those who worked with him either briefly or on and off – have their own books to write. The final category – those who met him briefly and are gleeful about making a few bob out of it – is the one that I must try and go to my happy place when I hear about. I don’t think I’ve ever written this word in any writing before, but there are some people who are just behaving like plain old cunts (among others, I’m talking to you, Lesley-Ann Jones, you hack; I’m flattered you blocked me on Twitter out of your own guilt and glad to hear that your shitty book has tanked). Rather than being ashamed of themselves, their greed and narcissism, like a normal human would be, they delight in the attention their falsehoods bring them. But that’s it, isn’t it? He’s no longer someone who belongs to me, to you, he’s everyone’s, for a while at least. He’s a face on a t-shirt in Camden Market.

We’re all still trying to process what life is like without him. The transformation of our fandom, which is out of our control. Mostly, I just feel… grateful. Lucky. That I exist now, a miraculous pinprick on this spinning rock, and that I existed at the same time as him on a planet 4.5 billion years old. That he made music that I’ve sewn into myself, grafted onto my heart. That he told me about non-music things (like art and philosophy and literature) like an inspiring teacher. That he gave me non-music gifts, like people who I’d never have met if not for him, who I lived half a world away from and had a one in 7.4 billion chance of meeting. It was all one way, from him to me. I’ve nothing much to offer, there’s nothing much to take…

Let’s wrap up part one: the ‘before’. I can close my eyes and think of how I felt walking into the New York Theatre Workshop on December 9/10, 2015. Excitement, trepidation. Ready to fall in love with him for the thousandth time in 30 years. So high it made my brain whirl. Dear friends around me, joined together from all over the world to celebrate the second part (after The Next Day) of this most unexpected return, after nearly a decade of near-silence. Hugging and crying, drinks and hangovers, singing and laughing into the early hours, and the next day and the next. That was how New York felt, and will never feel again.

Tomorrow that context changes, which is fitting in itself as who else was he but someone constantly on the move? Never look back, walk tall, act fine. Much more than ★, Lazarus is the exile’s legacy. It’s an audacious wink from beyond the grave about resurrection. It’s about a man who left England when he was young but spent the rest of his life collecting art that reminded him of home. Spent his last overseas trip taking his child around old London addresses. Spent one of his last songs talking with sadness of never being able to visit England’s evergreens again. The sailor who spent his life travelling has executed his master plan, which will leave me forever in awe, and is finally home.

_____________________________________________________________

Before I start, on this fine morning, where I awake to the frankly unbelievable news of my team having beaten the biggest and best in world football, I would like to say that I loved Lazarus in NYC. Sure, it didn’t make a huge amount of sense, I thought Walsh’s book was a bit of a mess and I was just happy to have the songs carry it home. I didn’t really like Cristin Milioti as Elly and the Greek chorus of girls had a fairly undefined, shaky role. The supporting characters felt a bit underwritten too. It had the air of an idea being worked out; after all, the clue is in the title. The New York Theatre Workshop. My dear friend Jake, the most knowledgeable theatre nerd I have ever known, told me that it was going to be much bigger and better in London, and that the intention was always to bring it home and watch it soar. We agreed that the NYC production was, essentially, a dry run for the real thing. I still treasure every second of the NYTW production, for what it gave me at a particular time, and that holiday will be something to remember forever.

So, you can understand that I had felt a bit anxious about seeing it again, kind of fearful that it would have the same affect on me as ★. That it would have its second meaning – it’s all about his death – revealed to me as the album did. That I would find it hard to get through without crying. That it would be, frankly, a depressing experience in the world of ‘after’. Absolutely none of those things happened. I’m as surprised as I could possibly be. To say the producers and creatives have pulled this show together is to commit a great understatement. It has taken all the elements that Bowie and Walsh and Van Hove put into the NYTW production and tightened them beyond what I thought was possible. There are entirely new sections of dialogue. There are performances that soar in a way they never did before (primarily Amy Lennox as Elly, with singing and acting of top quality – Always Crashing, I never thought it could be like that, with some light in it). Everything is bigger. The stage set is several feet larger all around, and this suddenly allows everyone the space they need to tell this story properly. The dialogue is polished and sharper, the central performances given the breathing space to be even better than in NYC from Hall and Caruso. It’s not at all about death. It’s about love, it’s about defeating forces that try to stop love from working, it’s about mental illness (a very old subject for Bowie to get back into), it’s about letting go. All the bits that didn’t quite work in NYC have been coalesced here. It is a truly, properly fantastic play. A theatre experience that absolutely works as a piece of art, not just a collection of great songs on a piece of string with some ropey dialogue holding it all together. There are still some rather Broadway moments (mein herr!), like Changes and Life On Mars, but that’s fine, you must allow a touch of glamour!

The final scene, of course, is still a bit of a wrench. The dialogue about reading to his ‘daughter’ on the hill, the farewell, it’s hard not to see the real life behind that. I felt a bit choked up, a heartstring tugged, but you know… Heroes will do that. He gave it greater meaning in the 2000s himself, following 9/11, and on tour, and it’s intensely powerful here. Even the photo of Bowie at the end on the screen was fairly unobtrusive and not made a big deal out of (though it isn’t needed and I still think they’d do well to drop it).

I do not subscribe to the idea that The Next Day’s songs were destined for this; rather that he fitted them around bits of the story. So on the album Valentine’s Day is about a school shooting, but here it’s the big theme for the murderous, psychotic Valentine – played with so very much more menace and darkness, eliciting genuine dread, by Michael Esper than in NYC. The Next Day is a backward-looking album, his only one. It’s taking stock, it’s angry, it’s partially a statement on the 20th century’s wars and religion and their effect on culture (I’d Rather Be High, Grass Grow, The Next Day). It’s wistful for England (Dirty Boys), wistful for Germany (Where Are We Now?) and coruscating on those who deserve it (You Feel So Lonely…). It even finishes with a nod to where he’s going next, as he often did, with Heat. It’s about love and mortality and the future. It’s about a man with a young child and a heart condition coming to terms with his own fragility. It’s actually not ★ but The Next Day that makes more sense now, because of Lazarus. ★ is nothing to do with this play, beyond the song Lazarus, which he only put on there, quite clearly, to promote his final masterwork. The remaining three new songs come alive here in a more convincing way than his versions on the cast album (though, as ever, nobody delivers a song better; No Plan destroys me). Killing A Little Time is absolutely thrilling here, though the ★ band version is a level up again. The sung counterpoints of When I Met You give the song a real electricity jolt. And the new band, led briefly by Henry Hey before he goes back to NYC next week, are also more convincing and well drilled.

All the creative decisions that were made for this London run worked. Jake bumped into the director, Ivo van Hove, on the way in (ok, in the loo) and told him we saw it in NYC. He replied, “I can’t believe how big it’s gotten!” You’re not kidding. Everything simply makes more sense now, like the characters’ motivations and how they’re played. It’s about 20 minutes shorter, cuts have been made that work, speeches have been created that illuminate and songs land that hadn’t quite nailed it before (like Where Are We Now?). The visual projections dazzle and have new supercuts flashing past that will let me spot new things each time I see it (caught a fast flash of Boys Keep Swinging after the final wig comes off). I do think it made a bit of a difference to be seated right in the centre of the front row, with Valentine hovering over my head, getting to see the intricacies of the facial expressions and interplay. Having said that, I can’t wait to see it again (hopefully soon) in another seat. Then in another. Even from the back row, which must feel like a mile away.

I thought it would make me sad, make me think about him not being here. But, unlike the album, I can now see that it wasn’t designed that way. They’ve made his lifelong dream of writing a brilliant musical come true. It does him proud, and I am so proud of him for making it possible.

David.

I’ve not felt like writing this year at all, but I know from previous experience that when that feeling is ready to pass I will just get this… compulsion to put fingers to keys as there’s something I need to get out. I’m still processing the last six months, which have contained the most significant personal events since my mother’s passing nearly four years ago. I know what loss feels like. In the last few weeks I’ve talked to several friends who’ve asked for my version of events so, perhaps in some desire to not forget anything, I’m going to try and write down what’s happened.

As it’ll be long I’m making a decision to do something I’ve never done before, not a diary exactly, but to split the events into different months. A friend told me that the lead-up (the play, the album, the holiday) to Bowie’s passing is the most remarkable part of my version of the story, and I know what she means. She asked me if there was a word to describe how that feels – to be on the top of the world, with no idea something awful is coming – and I don’t think there is, but it’s certainly… cruel. Perhaps all this would have been easier if he’d shuffled off this mortal coil in 2007 or 2009 or 2011, when he was just doing his thing, at home, with seemingly no interest in making music at all. I now realise how lucky we were not to lose him in 2004. Gail Ann Dorsey relating what happened when he had the heart attack, which nobody present had spoken about before, chilled me to the bone. But he didn’t die in 2004, or during 2012, when he was making his return record, The Next Day. He came back and gave us three more years of music, which only seems to have made coping with losing him worse.

One day perhaps a book will be written about the making of Blackstar. But, briefly, what we know so far is that during his cancer treatment he went into the now-closed Magic Shop studio two blocks downtown from his Manhattan apartment and recorded in the first week of each month of January, February and March 2015, as much as chemo would allow (I know all about the effects of chemo, sadly, and one week’s work in a month sounds about right). His initial idea was to continue the collaboration he started with Maria Schneider the year before on Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime) (single edit), but by then she had committed to her brilliant Grammy-winning record The Thompson Fields. As she couldn’t help out, and he didn’t have time to waste, she recommended one of her principal musicians, saxophonist Donny McCaslin. She pressed a CD of his excellent album Casting For Gravity into Bowie’s hand and advised him to visit the jazz club Bar 55, which he did without fanfare, to see Donny’s quartet play. He invited the band (on drums the remarkable Mark Guiliana, Ben Monder on guitar – they both appeared on Sue – Jason Lindner on keyboards and Tim Lefebvre – whose day job is with the Tedeschi Trucks Band – on bass) to play on Blackstar, sent them highly evolved demos and they made the album. That’s the short version of what happened. Tim Lefebvre has done some excellent interviews about the process, like this one, which are well worth seeking out. Bowie and Visconti produced the record and it was completed over the next few months. At the same time, incredibly, Bowie was also working, with playwright Enda Walsh and director Ivo Van Hove, on a sequel of sorts to his first starring role, The Man Who Fell To Earth. He would record/produce Blackstar during the day then head to Enda’s flat to co-write this new play, Lazarus, at night. It was a race against time in every sense. That’s the background. Here’s where I come in.

August

Lazarus was due to premiere in New York in December. I can’t remember whose idea it was to go, but it was based on getting tickets to the opening night, which our wonderful community of Bowie freaks had decided on as the night we all should go. When they went on sale Leah and I were at the mercy of friends who’d joined the New York Theatre Workshop and we crossed our fingers for a pair. Charlie Brookes was our saviour and tickets were procured (on the night, BowieNetters dominated the theatre, with probably 60+ of the 198 seats taken up by friends), at which point the search began for accommodation and flights. Division of labour is the best way to plan a holiday, so Leah did the flights while I trawled Airbnb for suitable apartments. The first couple of days were fun, looking into people’s houses and lives, but the novelty wore off quickly. After a long week of searching I found a pretty perfect, sparse, one might say minimalist, 3rd floor walk-up apartment on East 14th Street and Avenue B. It was near NYU, where Leah would work during the day (it’s how she got a week off work mid-term, by being a visiting scholar). Everything was booked.

September

Nothing momentous, comparatively, happened this month. I worked on an inflight magazine. I went to see the Rocky Horror Show a few times. We went to see Morrissey, which was, as ever, fantastic. My 16th time seeing him – that’s one more than Bowie. Though if we’re going to be technical and nerdy about it, which I always am, I’ve seen Moz 17 times because there was that gig at the Roundhouse where he sang three songs and walked off (lost voice), but I also saw Bowie in person twice more for TV shows, so really that’s 17 as well. I digress.

October

Bowie announces to my excitement that his new album Blackstar will be released on his 69th birthday on January 8th 2016. The Blackstar single and video were to be released on November 19th and it felt like all was good with the world. A New York trip to look forward to and a new album were more than I could ever have hoped for. I think now of how we all waited nearly a decade between Reality and The Next Day and it seems like another lifetime.

The week before the song premiered, my friend Mark and I drove to Cambridge University on the 11th to see Leah do a talk about Bowie and what was coming. At that time we had only a 30-second clip of Blackstar from the opening titles of the Sky series The Last Panthers (directed by Johan Renck, who also did both Blackstar videos). It was a fun evening, filled with excitement about the new record and a seriously brilliant presentation on his music (yeah, not on his hair or his clothes; on his creative practice and life as a composer, plus awesome data analysis).

On the 17th dad, Leah, her partner Ben and I went to see the Maria Schneider Jazz Orchestra at Cadogan Hall, near Sloane Square. We sat front row and it was just fantastic, what a great night. McCaslin, who dad says reminds him of the late, great Michael Brecker, was the lead soloist, blasting away five feet in front of me, and I had not a clue in the world he was on Blackstar. I heard the song for the first time two days later.

I feel so grateful now that I have a relationship with Blackstar, the song, which predates the events of January. The video (shot in September) is a masterpiece and I obsessed over it for days, then weeks. The song I think is absolutely one of the best he has ever done, and it’s starting to rival Teenage Wildlife for my Bowie Desert Island Disc. I did think he looked old in the video but then, he was pushing 70 and the flattering camera filters and copious make-up used for the videos from The Next Day were clearly no longer being employed. It was clear to me that he had finally released all vanity and was just being seen; he looked so engaged, enthused and vibrant in the video, and it gave us all so much pleasure. Some fans had said they hated jazz then had no choice but to grudgingly accept it when Sue came out because it was such a brilliant record. The same people were now faced with yet more non-pop music that challenged them, which as a jazz nerd I took a perverse pleasure in. Bowie does jazz? Then hires five jazz musicians to play on his last record? It’s like all my Chanukahs came at once.

December

For the first time since Bowie last toured, a big contingent of British (and some European) BowieNetters made their way to New York, to be united with our American BowieNet family. Leah and I arrived on Saturday the 5th, in the evening, and decided to do a bit of grocery shopping and spend our first night in the apartment. My recollection is that we watched The Wiz Live! on TV and fell about laughing at how terrible it was. We met up with the legendary Dick Mac on Sunday and went to the famed White Horse Tavern, once the haunt of Dylan Thomas, Kerouac and other luminaries, and then for dinner. It was at that point that I met Paul, Leah’s friend from Brisbane who’d come over for the show. What a fantastic guy, I adored him from the first minute. We headed over to Otto’s Shrunken Head, a dive bar three doors away from the apartment (we’re no fools!), to meet up with Bowie friends. My remembrance of the evening is somewhat coloured by pints of cocktails followed by a 4am stagger into bed.

The Monday contained perhaps the worst hangover I have ever had. Mountains of sushi did nothing to calm it, so as Leah went to work I hooked up with my wonderful friend Jake, my daytime companion, and off we went on a pilgrimage I’d always wanted to make, one that my mum talked about often, which was to see the grave of Miles Davis, up at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. I felt so ill, I can’t even tell you. But we made it, with Jake’s excellent navigation, and I paid my respects, which mum would have been proud of, before we headed to Harlem to visit Langston Hughes’s house then eat at Sylvia’s, the legendary soul food place. I put my head on the table and struggled through a bit of food (mac and cheese, and little else; not much available for the vegetarian). We went to the legendary Apollo, where I bought dad some gifts (and impressed the guy behind the counter by identifying Miles in a photo collage in two seconds) and then walked down to Central Park, laughing hysterically all the way. We were a bit worried about Lazarus not being any good and had a few parodies ready at its expense (mein herr!). Jake was flagging and bailed out of evening activities, which were dinner at Sigiri, a Sri Lankan restaurant (too spicy, I was still ill), followed by some live band karaoke at Arlene’s Grocery.

This was the day of the play’s press night – Monday the 7th – and many of our friends had gone to the theatre to wait outside to see if Bowie would turn up. It never occurred to me to do the same, it’s not my kind of thing. I saw him live plenty of times, I didn’t need to watch him walk into a theatre for five seconds, but I’d be lying now if I said I wasn’t at least slightly regretful that I didn’t get to see him in person one last time. At dinner, Leah showed me the pictures that had been posted on our Facebook group; indeed, he had turned up of course, looking happy and handsome, taking his bow on stage at the end with Ivo and the cast. Friends came to join us at dinner, straight from the theatre, looking high and glazed, having laid eyes on him for the first time since 2004 (a few others had seen his final live appearance in 2006).

That night at Arlene’s Grocery (Leah performed Superfreak and I don’t think I’ve ever laughed so hard in my life) was one of the most fun nights I can remember. Everyone was so incredibly happy. To be in New York, ready to see his play, most having seen him in the flesh earlier in the evening, it was a beautiful, special night. People got up and sang and the organisers were amazed that so many of us in the bar had flown over just for the play. I think we watched Tootsie when we got home (might have been the night after).

The next day, Tuesday, after a bit of gift buying, Jake and I spent the afternoon in the Mad Hatter, a Man City pub, believe it or not, watching City play. We won in the last few minutes, which felt fitting for such a trip. Then we all went to a friend’s party at her apartment, which was so much fun, one of those proper New York evenings where you feel like you’re in a movie. I wasn’t sleeping well of course, in a strange bed, using earplugs to block out the famed NYC hum, but I didn’t care. Subsisting on four hours a night on holiday is par for the course, even if it does later in the week lead to sleep-deprived, jetlag-induced hysteria. I don’t think have ever laughed as much as I did on this holiday.

Wednesday was Lazarus day and my friend Kate was flying in just for the show. I had not seen her in several years and we’d arranged to spend the day together. After another play of Blackstar on You Tube, Leah went to work and I went to Katz’s Deli on East Houston for breakfast as I waited for Kate’s plane to land from Ohio. She’s a hairdresser and we had organised to meet at the Aveda salon on Prince Street. In between Katz’s (a 10-minute walk downtown from our apartment) and Aveda is a building on Lafayette Street we now no longer need to pretend we don’t know about. There is a collection of penthouses and Bowie’s family live in two of them. I’ve walked past it and looked up many times over the years, even though I didn’t know which penthouse was his and nor did I care. It was kind of lovely to just know he was up there, tootling around in his man cave, making demos in his studio, reading and emailing incessantly, doing school stuff with his daughter, just doing New York things. A friend of mine, Lori, who works downtown, said that she would always wave up to him if she happened to walk past the building because she knew “he was up early too”. She didn’t wave because he could see her, nor did she walk past because she ever wanted to bump into him on the street (can you imagine! I’d have run a mile if I’d ever seen him slinking around, with his flat cap on). She did it just because he was there, and it was good to know he was just living life in his city, like we all live our lives in our cities and towns. I walked right across the front of the building to get to the salon and I looked up and smiled, wondering if he was happy with Lazarus and how the press had received it. Kate’s plane was delayed so I took a walk around the neighbourhood and popped into the Taschen store on Greene Street, which happened to have Mick Rock’s huge Bowie book on display. When Kate arrived we leapt into each other’s arms like we’d been apart a hundred years. After a quick drool over the Bowie book back at Taschen we got a ludicrously slow taxi uptown to meet a friend of hers for lunch, then came back down to meet up for a long coffee date with a big cheese at Aveda. He was English and seriously good company, the kind of guy who remembers very little of the 90s in London. It was time for Lazarus.